Drug traffickers, extortionists, and bank robbers keep posting clues to their crimes on Facebook

In late September 2017, agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in Seattle arrested a large-scale heroin, cocaine, fentanyl, and methamphetamine dealer named Francisco Ruelas-Payan. He later pled guilty to charges of drug trafficking and money laundering, and was sentenced to 15 years in federal prison.

In late September 2017, agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in Seattle arrested a large-scale heroin, cocaine, fentanyl, and methamphetamine dealer named Francisco Ruelas-Payan. He later pled guilty to charges of drug trafficking and money laundering, and was sentenced to 15 years in federal prison.

While phone records and GPS location devices were useful in helping investigators keep tabs on Ruelas-Payan’s location and near-term plans, it was his public Facebook activity that not only confirmed many of these leads but also offered additional clues authorities used to build their case.

Ruelas-Payan posted lengthy videos to the social media platform of himself driving to suspected drug deals, according to a DEA search warrant application unsealed late last month. The trips were further corroborated by GPS data from electronic tracking devices investigators placed on Ruelas-Payan’s cars and phone.

“During one of the videos, Ruelas-Payan points out a red pick-up truck and shouts out his window in Spanish ‘good-bye pig!’” said DEA agent Geoffrey Provenzale in a sworn affidavit. “Based on my training and experience I know the term ‘pig’ is a derogatory term for a police officer.”

One of Provenzale’s colleagues drove a red pickup truck during their investigation, the affidavit explains. And while the red truck Ruelas-Payan saw was not the one the DEA was using to follow him, the video revealed that Ruelas-Payan knew law enforcement had been watching him.

Social media has been used in police investigations for some time. In a 2012 survey, 4 out of 5 law enforcement officials said they used social media to solve crimes, and nearly 7 out of 10 said social media helps to close cases faster.

Facebook received nearly 130,000 data requests from governments around the world during the first six months of 2019, according to the most recent figures available. Between January and June of last year, the US government requested data from Facebook related to more than 82,000 accounts. About 88% of those requests were granted. The second-most requests came from the government of India, which asked for data on 33,000 accounts. Facebook agreed to provide about half of them.

Yet people often leave a trail of clues on their public social media profiles that investigators can see without ever needing a subpoena.

Some, for example, take to Facebook Live to discuss an impending $10 million extortion attempt:

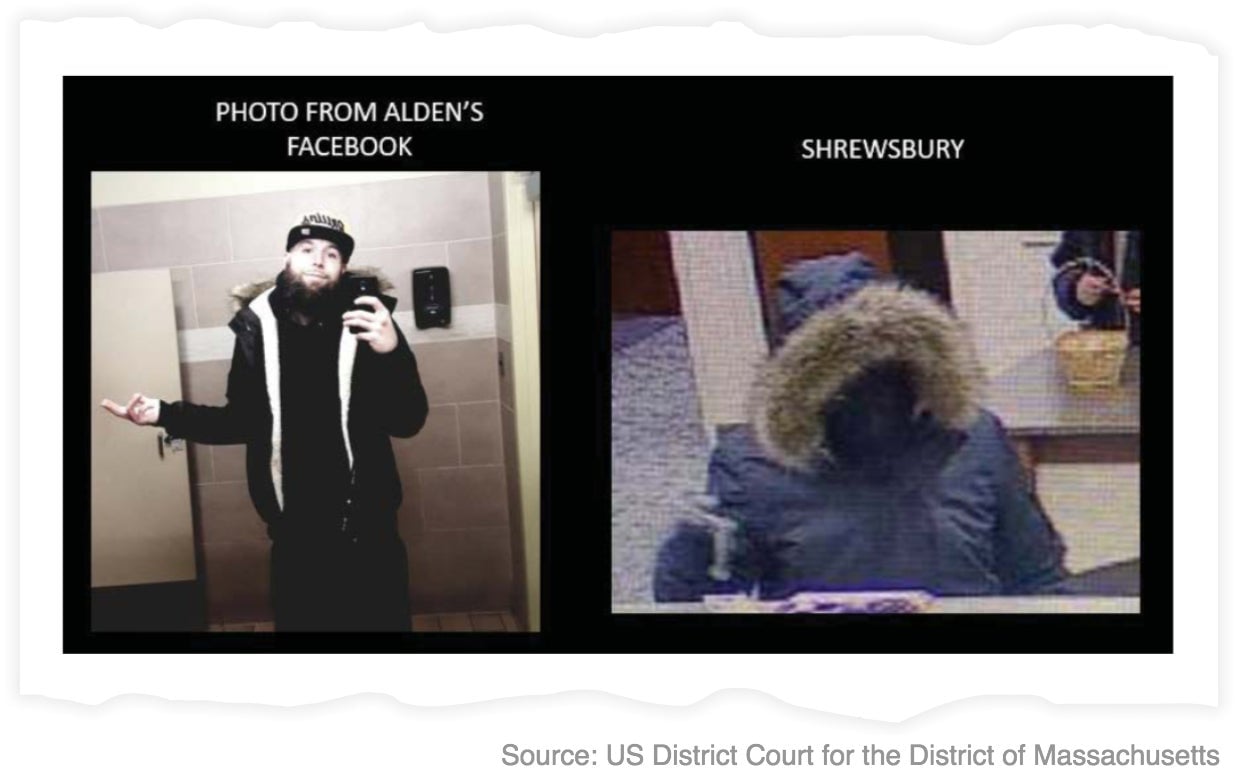

Others post selfies in the same clothes they wore while robbing a bank:

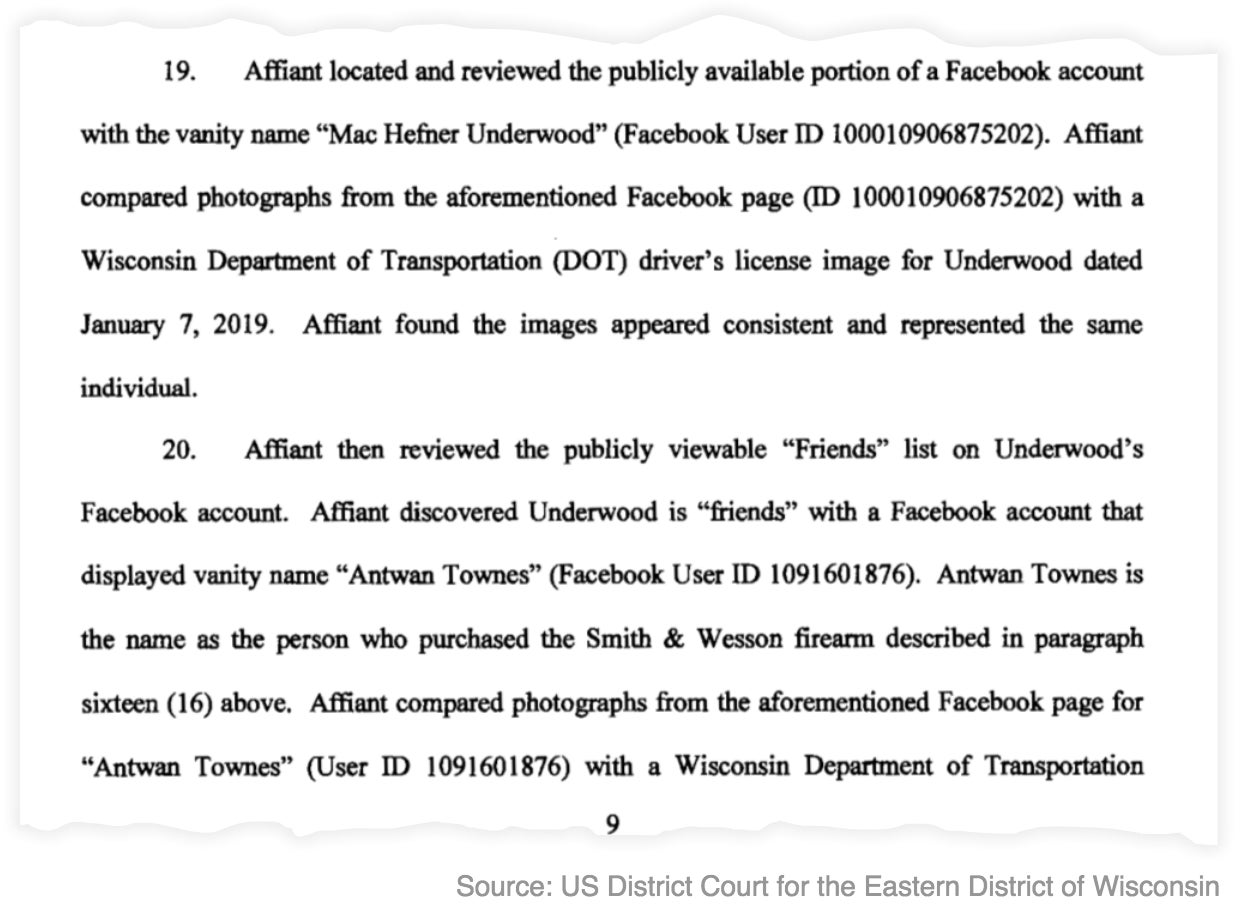

Other times it’s a “friends” list that firms up an investigator’s hunch:

“If I was still running a squad, we could make a living just off of this foolishness,” Joseph Giacalone, a former New York City detective sergeant who now teaches police procedure at John Jay College, told Quartz. “Social media has made fools out of a lot of people. The ‘look at me’ generation can’t help themselves.”

While Facebook helped to trip up Ruelas-Payan, his cousin and business partner, Jesus Octavio Rodriguez-Payan, proved to be much more cautious. He managed to slip back to Mexico after his cousin’s arrest.

“[Rodriguez-Payan] appear[ed] to be much more careful about posting any activity on his Facebook page,” the warrant application says, adding that while “multiple photos [were] displayed for public viewing,” there was no “criminal or asset information” to be found.

“I believe, after DEA arrested multiple associates of Rodriguez-Payan during September 2017, Rodriguez-Payan became more cautious and stopped posting any photos on his Facebook account so as to not let law enforcement learn any possible clues about his location or activities,” Provenzale explains in his affidavit. Rodriguez-Payan, his mom, and the mother of his children, all changed their Facebook profile names, making it harder for investigators to track them.

Investigators, however, knew Rodriguez-Payan was still active on the platform because he “liked” at least one posting by another of his Facebook friends.

“It took me multiple months to fully identify Rodriguez-Payan even once I was aware of his nickname and the target Facebook account,” Provenzale’s affidavit says. “He was eventually identified through documents he was forced to put his real name on, such as airline tickets and Department of State information.”

Eventually a federal judge signed off on a warrant that directed Facebook to turn over details of Rodriguez-Payan’s activity on the site, including private messages and location information, to the DEA. This, combined with cellphone records, wiretaps, and GPS tracking data, created a digital dragnet too large to evade.

Rodriguez-Payan, now 22, was arrested last year trying to enter the United States from Mexico. Earlier this week, federal prosecutors asked for an 11-year prison term. He will be sentenced March 9.