Losing our jobs to robots may subconsciously be changing the way we vote

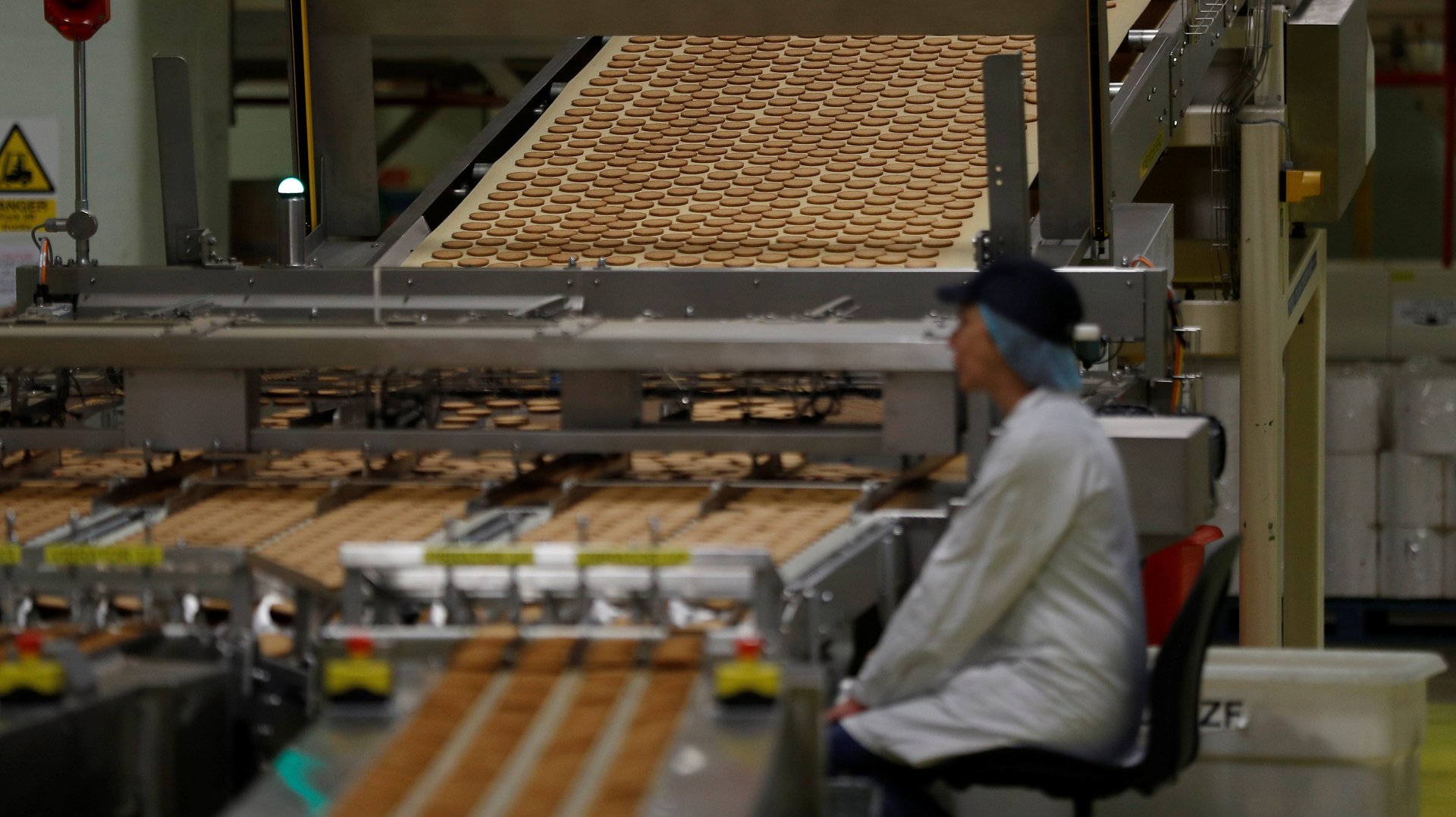

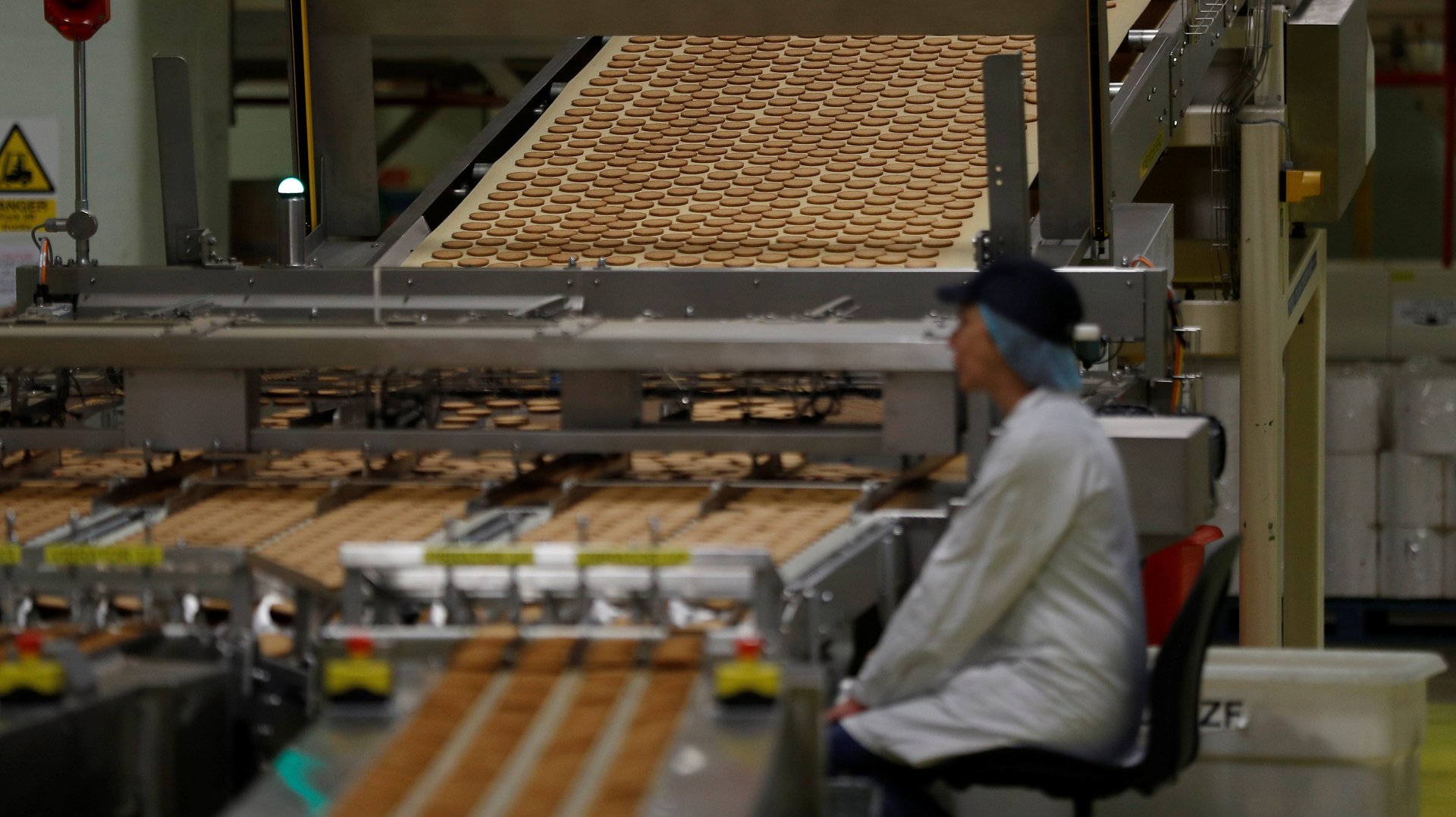

Automation—the idea that more and more jobs will soon be done by machines rather than people—is a conscious fear for some workers, and a latent pressure felt by many others. Now, a UK study has linked the potential risk of automation with how people vote.

Automation—the idea that more and more jobs will soon be done by machines rather than people—is a conscious fear for some workers, and a latent pressure felt by many others. Now, a UK study has linked the potential risk of automation with how people vote.

A recent study from the Institute for the Future of Work, a UK non-profit, compared two data sets for England: The likelihood of jobs becoming automated, sourced from the Office for National Statistics (which provides plenty of detail on how it calculates those probabilities), and voting behavior in the 2016 UK Referendum on membership of the European Union, in which the UK voted to leave by a narrow margin.

They discovered a clear correlation between the risk that people’s jobs and the tasks within them will increasingly become automated, and likelihood of voting to leave:

Boston, a small port town in the East Midlands where the local economy is dependent on food farming, scored highest on both measures. At the other extreme were university cities Cambridge and Oxford, as well as many London boroughs.

Like other Brexit studies, the authors found that white ethnicity and birth in the UK were over-represented in the cohort that voted to leave the EU in the 2016 Referendum. But they added: “But the strongest correlation, by some distance, was between risk of automation and voting leave.” The results held when controlling for other variables like age, ethnicity, and wage.

Previous analyses of voting behavior have found that choices can often be influenced by threats to the labor market, as well as by other life conditions linked to our happiness and security at work—income, health, life satisfaction, class, field of work, social origins, education, and the ability to manage uncertainty. Automation is just the latest in a long history of shocks that hit people hardest who are poor, less healthy, less happy, and who lack financial or other buffers to help them through hard times.

To explain the possible link between automation and voting Leave, they use the theory that our experience of work spans a spectrum ranging from “included”—having a secure job with good prospects—to “excluded,” or long-term unemployed. They speculate that those in sectors most at risk of automation feel increasingly excluded, even if they do have work. “What is key is the growing number of people who anticipate significant change as work is transformed and feel that their labor market status and prospects are precarious,” the authors wrote.

Much anger and blame, which may have resulted from this sense of exclusion, appeared during the Referendum campaign to be directed at the EU in general, and immigrants from it in particular. This analysis suggests that the emotional reaction, though understandable, was misplaced: It’s not EU citizens coming for the jobs, but robots.