Here are the sources you should and shouldn’t trust on the coronavirus

Your timeline is a crowded social space full of updates, advice, cures, and warnings—and it’s causing a contagion of misinformation.

Your timeline is a crowded social space full of updates, advice, cures, and warnings—and it’s causing a contagion of misinformation.

But you can take steps to avoid ingesting bad data. Here is what to trust, and what to ignore:

The WHO, CDC, and NIH are A-OK

The World Health Organization (WHO), country-specific government agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the US, the National Health Service in the UK, or the Public Health Agency of Canada, are your best bet for health and behavioral recommendations. This comes with several caveats. If the information is cited in a legitimate news report from a respected source, you generally should be good. But double check the actual source: on Tuesday, Twitter users were sharing news about an infected celebrity from a supposed BBC account that was actually fake.

And with second-hand information, there have been some snafus. On Monday, the head of the WHO said that the “threat of a pandemic has become very real” and the statement was immediately twisted, and not by internet randos. Political scientist and head of the Eurasia Group Ian Bremmer tweeted that the WHO upgraded coronavirus to a pandemic—which it had not at that point (the official pandemic designation came on Wednesday). Bremmer took the tweet down, and Jane Lytvynenko, a Buzzfeed reporter who specializes in misinformation, admitted she’d fallen for this particular piece of false information as well.

Wash your hands of sketchy info

Even those who seemingly should know their stuff have proven to be wrong: a pharmacy in New York posted a recipe for a DIY hand sanitizer. The recipe, which a worker copied from the internet, was itself wrong, Business Insider reported, and would not help with actually killing germs.

The best course of action is to follow the tenets of “information hygiene,” the hand-washing equivalent of the online world: take 20 seconds to find the original source of the information, cross-check it between several legitimate sources (really, this is often a very quick Google search). Here’s a full guide for what to do. And a note on Googling “can i get coronavirus from…”: Google autocompletes its search box based on, among others, what other people are searching for, so do not use that as suggestions for actual infection risks. According to the CDC, you can get the virus if you are close to an infected person (within 6 feet) and through respiratory droplets when they cough or sneeze, and not from packages from China. (Update: a new study has shown it can also stay on surfaces for hours or up to three days, on cardboard up to 24 hours).

And don’t necessarily count on official sources being the end-all-be-all when it comes to updates on the disease. In the US, authorities have been struggling to gather information on coronavirus testing from the disparate state health systems, so the CDC stopped providing a full count of the number of people had been tested. You might want to check your local city hall or public health department’s website for information specific to your area.

Practice social-media distancing

It’s particularly important to take care on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or YouTube, which even in epidemic-free circumstances struggle to curb misinformation.

And misinformation about the coronavirus has flooded social media: Minor celebrities on Twitter declare vitamin C injections and zinc cure the virus while others say that garlic or hot water will do the same (there is currently no widely available treatment for the virus, although at least one experimental drug is being used ). If you are seeing medical advice on your platform of choice, it’s probably best to ignore it.

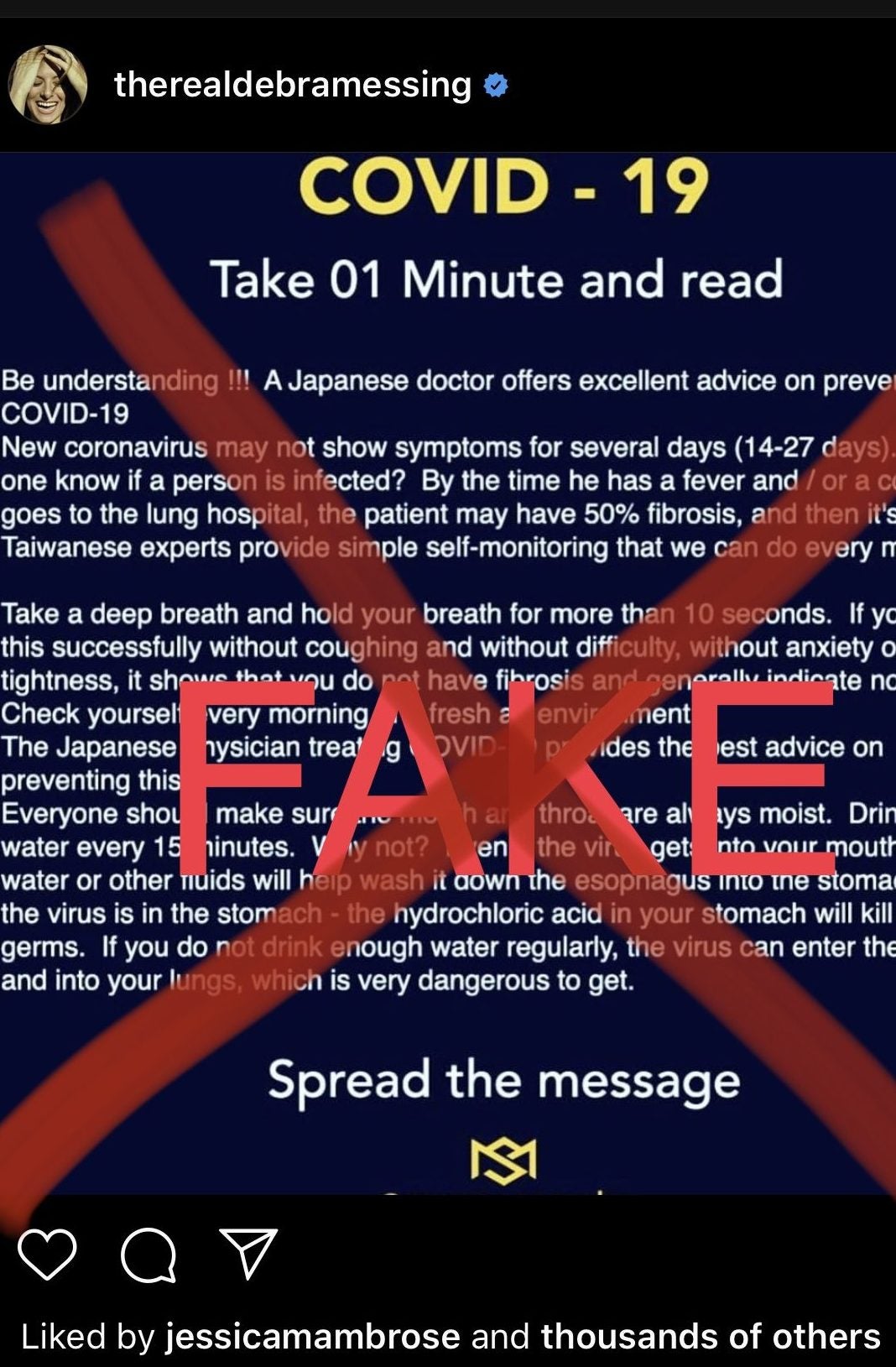

A widely circulated post, including by actress Debra Messing, claims you can check if you have the virus by holding your breath for more than 10 seconds. The information has been shared tens of thousands of times around the world, and it is not true, according to the WHO.

If you do dive in, be very careful to cross-reference that information with other sources, and make sure they are legitimate (some “doctors” on Instagram are not in fact doctors). If you must get your coronavirus information in your feed, follow the official accounts of organizations like the WHO and CDC. Facebook groups are some of the most notorious sources of health misinformation, and the coronavirus is no exception.

Medical misinformation can be deadly: at least 27 people have died in Iran from alcohol poisoning because they’d been drinking to “protect” themselves from the coronavirus. The rumor about alcohol being a supposed preventative measure had been circulating on social media.

Ignore “remedies” and “cures.” They don’t exist.

The wellness world in general will try to offer at-home remedies and miracle cures. We’ve seen an alternative health publication offering free energy healing, and a Facebook post about shoving colloidal silver up your nose. While neither of those are probably intentional disinformation, they could be harmful if someone sick turns to false cures over actual medical advice.

Many are trying to make money on coronavirus misinformation. One Quartz editor said she started getting health insurance-themed spam phone calls, while sketchy ads are making their way into many feeds.

With few exceptions, advertisers are trying to sell you something, and that’s all they care about, whether it’s air-purifiers on IndieGoGo or “an amazing, mushroom-based compound,” that readers can discover through an email from conservative news site Newsmax.

Facebook did give the WHO free ads to spread good information. The WHO is A-OK.