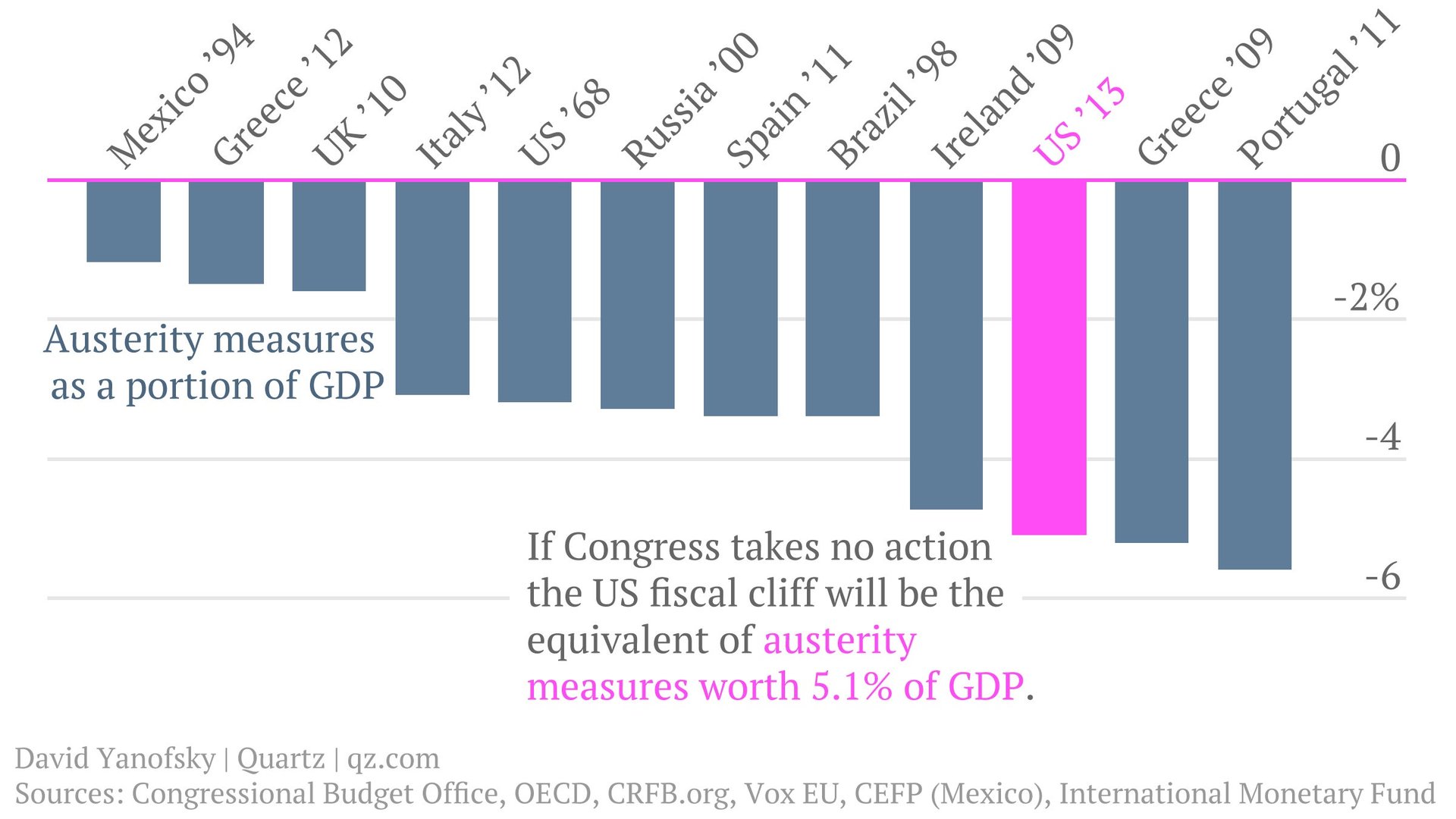

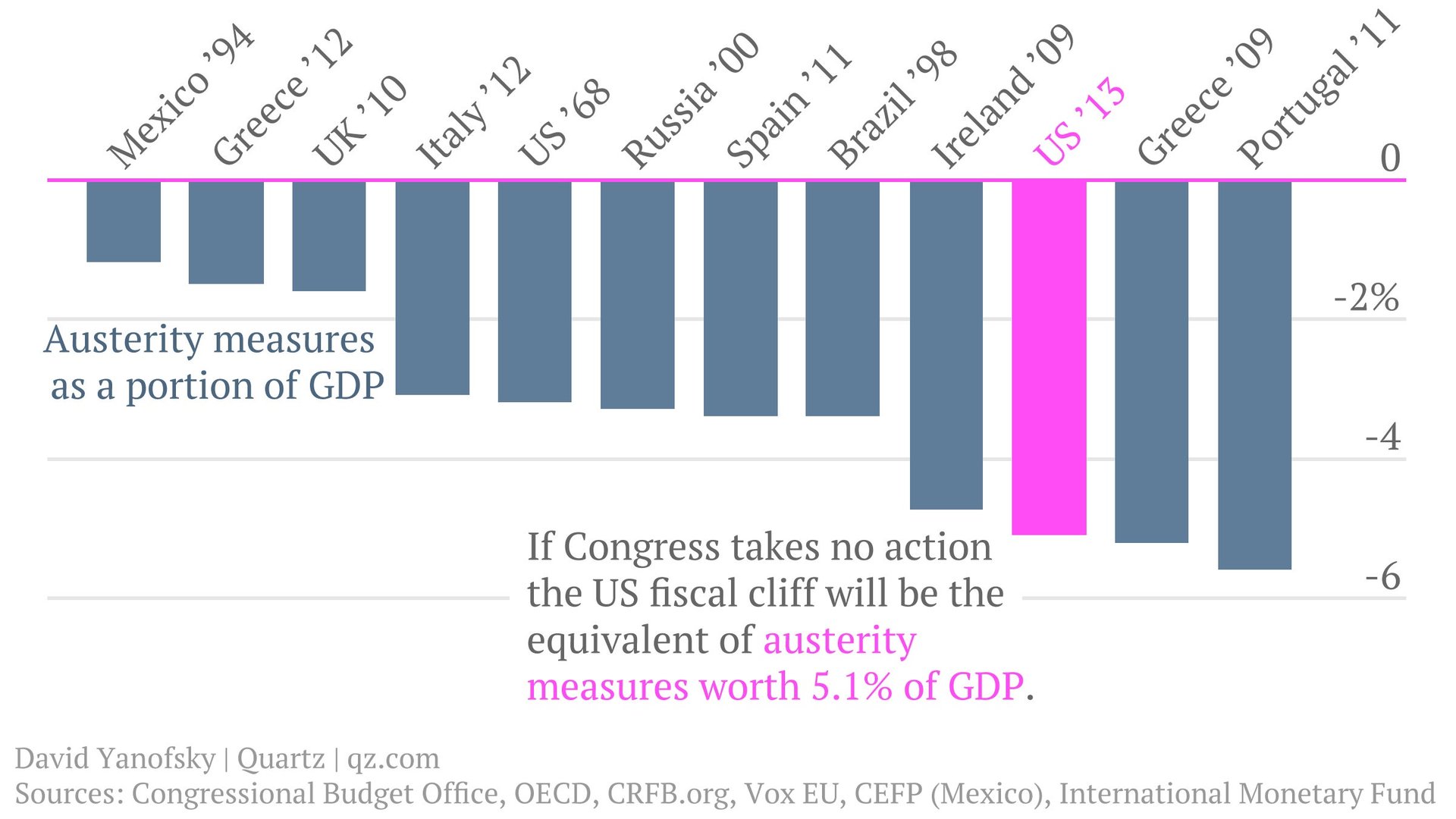

American masochism: The fiscal cliff is one of the most severe austerity policies in the world

It’s common conservative campaign rhetoric in the US: If unsustainable public debt continues to grow, America will end up in the same boat as Greece.

It’s common conservative campaign rhetoric in the US: If unsustainable public debt continues to grow, America will end up in the same boat as Greece.

But in fact, Congress is already way ahead of the curve in this respect. Absent new action, next year the US government’s budget footprint will contract more rapidly than those of Greece, the United Kingdom, Spain and Italy, all countries where post-crisis austerity measures sent protestors into the streets and growth plunging.

The so-called “fiscal cliff,” an automatic fiscal consolidation that Congress agreed to last year in a so-far-vain attempt to force itself to reach a more sensible deal, will start to take effect on Dec. 31, 2012 without government action. It resembles the programs of budget cuts and tax hikes that the International Monetary Fund often imposes on the troubled countries it rescues, or that are adopted by countries facing pressure from sovereign-debt markets. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that, unless another deal is reached, the US will see deficit reduction equal to 5.1% of gross domestic product in 2013, the steepest consolidation since 1968, when tax hikes lead to deficit reduction equal to 3.2% of GDP, and the 1969-70 recession.

How does that compare to both contemporary budget cutters and the bailouts of yore?

Greece consolidated by 6.5% of GDP over two years. In order to secure financial aid and debt relief, Greece implemented spending cuts and tax hikes between 2009 and 2011 that are larger than the fiscal cliff, but the extra time helps absorb some of the economic pain. Greece still wasn’t done after that, however, and agreed to a further 1.5% GDP of consolidation.

The cliff is as high as the austerity policies of the rest of the PIIGS. Troubled Eurozone countries Portugal, Italy, Ireland and Spain have all adopted controversial austerity policies; Portugal and Ireland received IMF bailouts and had the harshest one-year consolidations of 5.6% and 4.74% of GDP, respectively. Spain and Italy are both under pressure from their creditors and European leaders to reduce their debt loads, consolidating by 3.4% and 3.1% of GDP in recent one-year budgets.

The United Kingdom reduced its deficit by 1.6% in 2011-2012. In 2010, new conservative Chancellor George Osborne implemented an ambitious austerity program to consolidate government spending by 6.6% of GDP by 2016, and the first full year of work saw a reduction of 1.6%. With growth elusive and domestic critics howling, the program has become a staple of debates over austerity in advanced economies.

Ending the Russian ruble crisis required a budget contraction of 3.3%. After the country suffered a currency collapse in 1999, the IMF arranged a $4.5 billion rescue that required the country to adopt austerity policies in an effort to push back longstanding structural deficits.

In 1999, Brazil consolidated by 3.4% to qualify for a rescue. When structural deficits and hot money flows left Brazil vulnerable to economic shocks in the wake of Russia’s devaluation, the country requested the IMF’s help to deal with its creditors, resulting in a significant budget adjustment the next year.

The Mexican peso crisis of 1994-1995 ended with a 1.2% spending reduction. When the IMF stepped in to backstop the country, it included some moderate fiscal consolidation in the loan conditions, but two years of previous budget surpluses helped absorb the blow.

With the exception of Portugal’s one-year consolidation, the US fiscal cliff represents the most severe austerity policy in recent memory. Most advanced economies spread adjustments of that size (pdf) over several years to minimize economic disruption.

While the IMF is a historic advocate of orthodox economics, its recent public statements include a rethinking of the benefits of spending cuts and warning for the US: Don’t fall off the cliff, or the resulting recession—which could drop American GDP more than 4% next year—will damage economic prospects around the globe.

That highlights perhaps the most amazing thing about this set of policies: They are typically implemented against public opposition in the face of pressure from creditors and international organizations, but the US Congress put them into place during a time of historically low interest rates, against the wishes of the world’s most reliable institutional proponent of fiscal consolidation.