In Hong Kong, buying locally-grown vegetables is about more than just fighting coronavirus

Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in Hong Kong at the end of January, shopping for locally-grown vegetables has become part of Josephine Liu’s weekly routine. She goes to at Mapopo Community Farm, in the city’s North District, religiously almost every Wednesday and Sunday when the farm’s market opens, walking home with one or two big bags of greens—heirloom tomatoes, spring mix salad vegetables, choy sum—for her family.

Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in Hong Kong at the end of January, shopping for locally-grown vegetables has become part of Josephine Liu’s weekly routine. She goes to at Mapopo Community Farm, in the city’s North District, religiously almost every Wednesday and Sunday when the farm’s market opens, walking home with one or two big bags of greens—heirloom tomatoes, spring mix salad vegetables, choy sum—for her family.

Maintaining a healthy diet and sourcing affordable, fresh farm produce during the outbreak are her top priorities. Prices for vegetables imported from mainland China—once her normal source of produce—have gone up drastically.

“The vegetables they sell here are fresh and tasty. And most importantly, inexpensive. I spend about HK$100 (US$12.90) to HK$200 each time and it is enough to last for a few days,” said the 40-year-old housewife who lives close to the farm.

“To be honest, I don’t trust the farm produce from mainland China. I’m worried about the chemicals and the toxins in the soil where the vegetables are grown. There is no way I can trace the origin or know whether it is safe. And I’m more worried because of the recent situation of the coronavirus.”

But to Liu, buying locally grown vegetables is more than a health decision.

“Supporting local farms is a form of resistance. Eradicating local farms and local food supply is a way to force us to rely on imports from mainland. It is a way to tighten the control over Hong Kong.”

Like most people in Hong Kong, Liu used to shop at supermarkets. But since the Hong Kong protests began in June last year, the political unrest that gripped the city has led distrust in the local government. Resistance has evolved from street actions to the establishment of a “yellow economy“, which encourages people to spend money on protester-friendly businesses.

“People need to be given a choice. But now, more than 90% of the vegetables we consume come from mainland China. When the coronavirus hit mainland China, prices of vegetables soared because the supply chain was broken. To encourage people to consume locally grown vegetables is to encourage people to preserve a Hong Kong way of living,” said Becky Au, the manager of Mapopo Community Farms, whose family has been raising crops in their current location in Fanling for three generations.

Despite being one of the most densely populated cities in the world, only 24.9% of the 1,111 square kilometers (429 square miles) territory of Hong Kong is built-up. About 50 square kilometers—an equivalent to 4.5% of the total land area—is under agricultural land use.

Much of the agricultural land has been converted into other usage over the years since the 1970s and 80s as the city’s manufacturing and service industries began to thrive. But some of the former agricultural land—about 1% of the city’s total area—became “brownfield sites” which are used as storage or port back-up facilities. Property developers are holding at least 1,000 hectares (2,471 acres) of agricultural land in their land reserves.

However, according to data from the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, as of March 2018, only 7.1 square kilometers are farmed. Hong Kong only had 4,300 farmers working at 2,500 farms, an equivalent to 0.1 per cent of the city’s total work force.

Decline in local agricultural activities means Hong Kong relies on imported vegetables. A 2018 study conducted by Hong Kong Food Works showed that locally produced vegetables were still accounted for 30 to 50% of local consumption in the 1980s. But the self-sufficiency ratio plunged to a single digit in 2000’s, reaching 1.82 per cent in 2015. Government data showed that 92% of the vegetables consumed in Hong Kong came from mainland China.

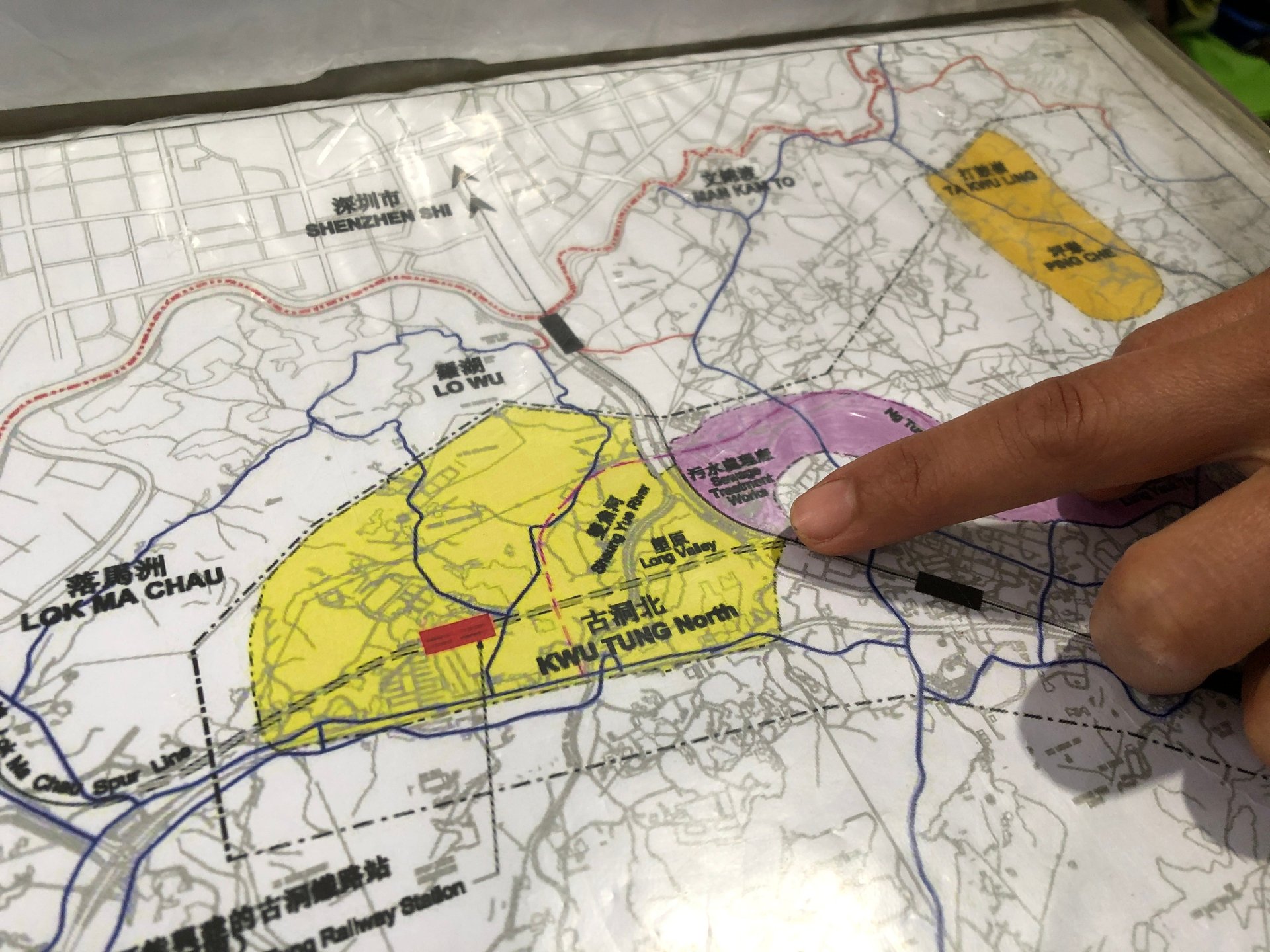

But that could fall farther still as the government revives a controversial proposal, first tabled a decade ago, to turn Kwun Tung North and Fanling North in the northeast New Territories into a new town to boost housing supply. The redevelopment plan will involve re-zoning agricultural land and it could eliminate some 100 hectares (247 acres) of farmlands in order to make room for 72,000 housing units. This led to a series of protests and clashes between activists and authorities—a rare sight at the time before the 2014 Umbrella Movement and 2019 Hong Kong protests.

Land shortage leads to expensive housing and crowded living space, with each citizen has only 170 square feet on average—an equivalent to an average car parking space. But many have argued that the government should develop brownfield sites first before repurposing farmlands.

Au set up Mapopo Community Farm against such a backdrop in 2010. The farm has been at the forefront of opposing the northeast New Territories development plan and she hoped to draw people’s attention to the importance of local farming.

A decade on, the farm has earned people’s support through farming workshops, guided tours, and selling to customers directly at the farm to encourage people to consume locally grown vegetables, said Au. Her family has also been exploring sustainable ways of farming, such as mixing their own organic fertilizers with food leftovers collected from neighboring restaurants. The farm’s market sells vegetables grown by not just her family but also other farmers.

Organic farming has become a leisure activity for the people of Hong Kong in recent years and 320 farms have participated in the government’s organic farming conversion scheme. But it was the outbreak of coronavirus that helped further raise the public’s awareness of the importance of local farming, she said.

The lockdown of Wuhan, a logistics hub in mainland China, since Jan. 23 has severely disrupted (link in Chinese) the transportation of vegetables to Hong Kong. Prices went up by 30% to 50% in February.

“We have been bringing food made from our produce to frontline protesters and journalists since last June, hoping to raise people’s awareness of local farms. But now because of this virus, people finally get it and they make their way to buy vegetables from us. We have been selling out almost every weekend,” said Au.

But local support and good business might not last for long. The redevelopment plan is expected to eat up the plot of land where her family’s farm is located later on this year, but Au was uncertain when.

Au said the government has offered to relocate the family’s farm to another remote location, but they will be moved to public housing instead of living on the farm like they are now. “It’s not possible to live away from the farm because of how we operate. Farming is a 24/7 job,” she said. “We resist, we protest, because we want to maintain our way of life.”