I’m a healthcare worker, and this is what it’s like to treat patients during coronavirus

The alarm goes off at 6:00 am. I was up until 11:00 last night charting, so I’m starting the day already exhausted. I get up and quickly get myself ready. I try to ignore, while at the same time disguising, the dark circles and puffiness looking back at me in the mirror.

The alarm goes off at 6:00 am. I was up until 11:00 last night charting, so I’m starting the day already exhausted. I get up and quickly get myself ready. I try to ignore, while at the same time disguising, the dark circles and puffiness looking back at me in the mirror.

I feed the kids, prep their lunches, feed the dog, try to get out the door by 7:40 am. Mornings are a thankless, but necessary, series of tasks. Normally, I’d have school drop-off for my two sons, but this week we’ve hired a babysitter, since schools are closed for the at least the next month amid the spread of the novel coronavirus. My husband and I both work in healthcare, so working from home full-time is not an option.

I’ve managed to cut back my work to mornings in the clinic, so I “work from home” in the afternoon, which basically entails frantically charting and calling patients during naptime, which is never long enough.

I’m a family medicine physician assistant at a federally qualified health center in Denver, Colorado. FQHC’s, as they’re commonly known, are a remarkable system of non-profit primary care clinics that provide medical, dental, and mental healthcare to patients regardless of their ability to pay.

We serve uninsured, underinsured, Medicaid, and Medicare populations, from newborns to geriatrics, both rural and urban. If you ever find yourself uninsured, search for your local FQHC. Because of our mission, we see more medically complex, underserved, and impoverished patients than your typical primary care clinic.

Many of my patients do not speak English. I am tasked with providing care and building trust with people, some of whom have been so traumatized by our country’s medical system that they would rather stay at home until their toes fall off than come in to a hospital for treatment they know they can’t afford. All the providers and staff at my clinic are there because they believe that everyone is deserving of high quality health care, and are committed to serving the most marginalized of our communities. I love my work. And, its exhausting.

“It’s chaos.”

Lately, with Covid-19 invading my already cramped mind-space, I find myself completely overwhelmed. Friends inquire about the status of the novel coronavirus daily, hoping that I have some inside scoop on the latest from the frontlines. All I can say its, “It’s chaos.”

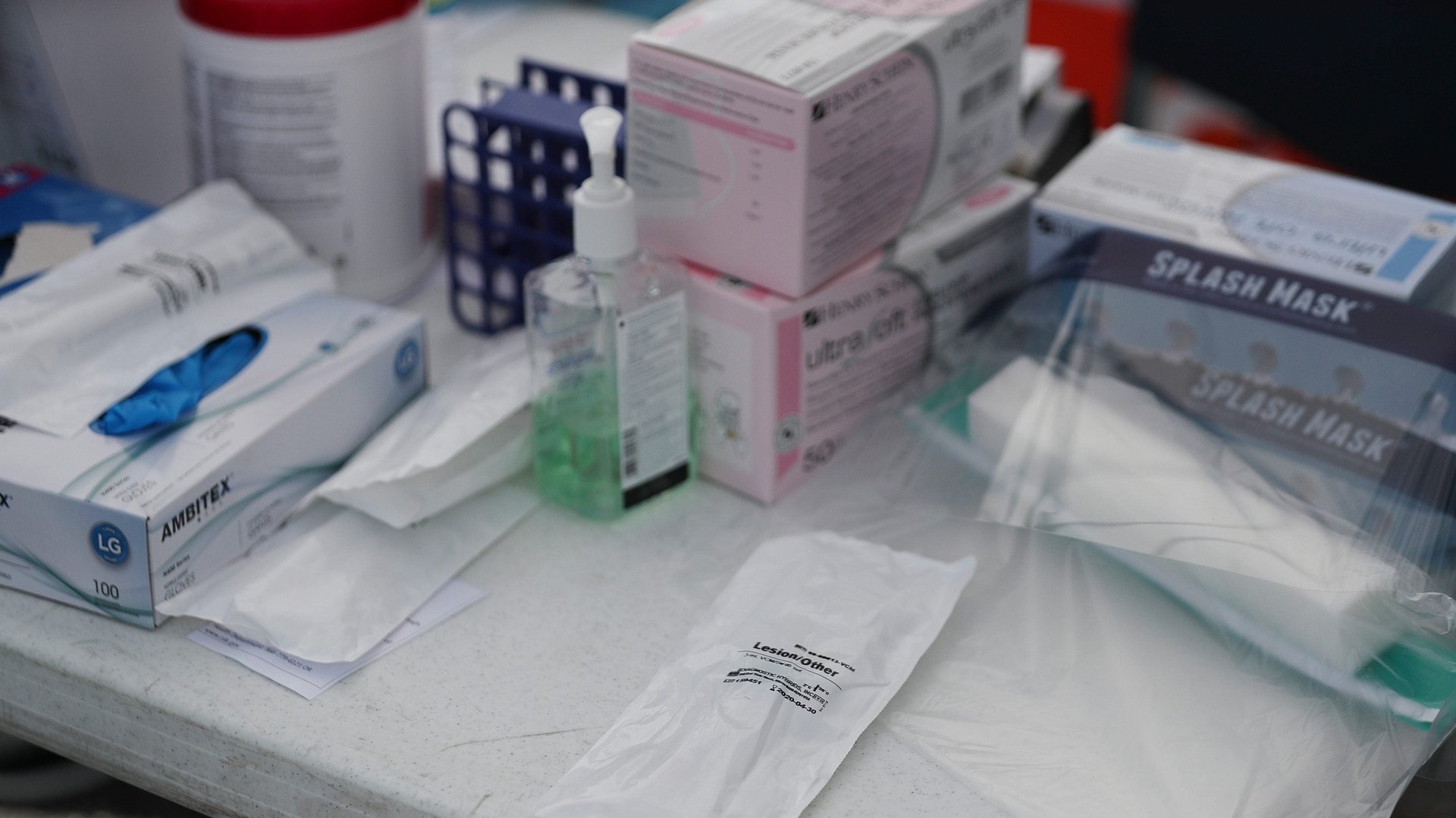

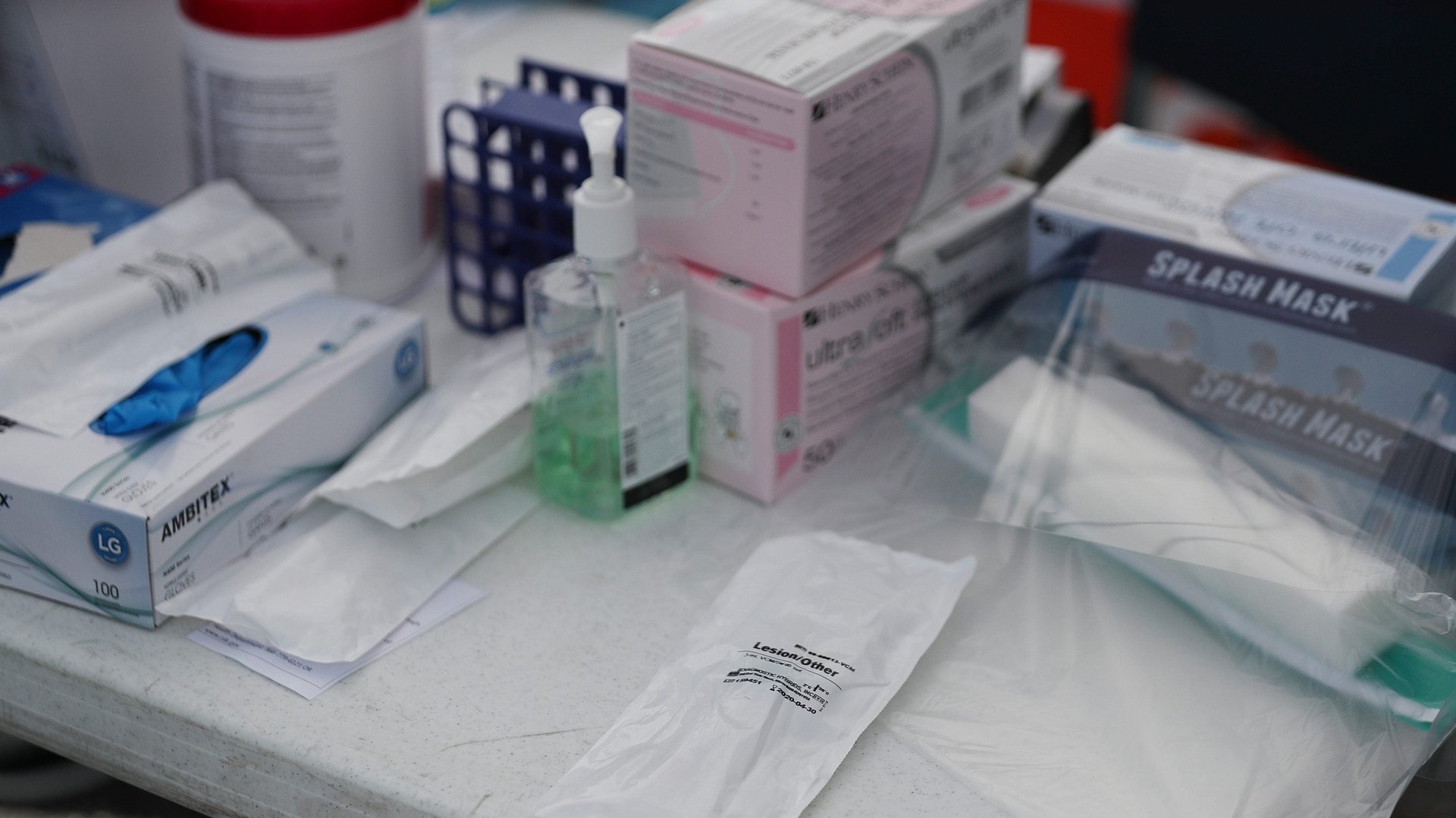

Official recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and my higher-ups change every few hours. Since the local guidelines are days behind the CDC, this also means we’re given conflicting information. Today, we’re no longer testing anyone for Covid-19 as an outpatient facility, due to the lack of tests. There’s a shortage of masks, both surgical and N95, so we are supposed to use one surgical mask a day, regardless of the obvious risk of contamination from contact with ill patients. We’ve been told to test for influenza and viral respiratory panels, but we didn’t even have equipment to collect those tests in our small lab until yesterday. We’re trying to keep up, but our leadership seems as confused as we are on the ground. I’m one step behind on crucial information, lack essential equipment, and drowning in community panic.

People look to me daily to provide some measure of reassurance. I have little to offer, but I’ve found honesty seems to provide the best balm. I tell my patients not to panic, that most people will come through this unscathed, that the best thing they can do is to stay home, avoid high-risk family members and friends, and to call if they develop severe symptoms.

“Just do your best with what you have.”

At the clinic, everyone looks tense and worried in the morning huddle. The daily recommendations for testing and isolating suspected Covid-19 cases has changed, yet again. Yesterday , we were told we need to conserve our limited supply of test kits, and to use a nasopharyngeal swab, or nasal swab, alone, instead of a second oropharyngeal swab, or throat swab. Only one person in our clinic had performed the swab before.

“Did we get the results back from the tests done earlier this week?”

— Not yet. So much for the 24-48 hours turn around.

“At this point, what do we do if they are positive?”

— Unclear answer, but basically, tell them to stay home, unless they are very sick.

“This just in, health workers with an exposure to positive Covid patients are no longer to be quarantined as long as they used PPE [personal protective equipment] correctly and are asymptomatic.”

Well, that’s a pretty big assumption, considering, we never use it and our screening process is a joke.

“What about the people we suspect are infected, but do not meet criteria to test? How are we ever going to get a true estimation of the severity of this if we don’t test all people with flu-like symptoms?”

—Just do your best with what you have.

The last drop of information from pipeline is fetid: “There aren’t enough masks, so please use one surgical mask per day. Make sure you are performing diligent hand hygiene before and after and avoid touching the outside of the mask.”

—Wait, we’re supposed to use a dirty mask all day?

“Oh, and Covid testing is now reserved only for patients in critical condition, there are no longer test kits available in the outpatient setting.”

—Seriously? Well, at least we don’t have to worry about nasopharyngeal swabs anymore. Heads shake. Its 8:30 am. Shoulders slump, and we make our way to our desks, which are not six feet apart. I eye my full schedule of sick visits from people convinced they have Covid, which take about an hour each. My colleagues and I will see patients in dirty masks, and with no way to confirm or rule out the diagnosis.

My first patient is here for a blood pressure check. She’s 65, with several relatively stable chronic medical conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). She casually mentions a cough, night sweats, and increased shortness of breath. She’s not wearing a mask. Crap. Too late to don PPE. I cross my fingers and hope it is just a run-of-the mill acute exacerbation of COPD. No fever, which is good, so hit her with some steroids and hope for the best. I’m already behind 30 minutes.

My second patient is pregnant, 35 weeks, and doing great. A quick swab and I rush her out of the clinic and away from all these sick people. Call if you feel sick, and go to labor and delivery if you start having contractions!

I have an STD check next. (Good lord, why don’t people wear condoms?) Next, another sick visit, a frequent flyer this time. (I’m not going to use the label hypochondriac, but… ) No fever, no cough, just nasal congestion and a slightly sore throat. Probably not Covid. But, what if it is? At this point, we’ll never know. The best I can do is offer supportive care and reassurance.

My last patient checks in 20 minutes late, but I’ll see her because she has no-showed the past few appointments. She can’t read, so using her insulin is challenging. Her daughter, who is supposed to be helping her, keeps falling asleep in her chair while her kid keeps interrupting and touching my hair. She needs to get her sugar down so that she can get a vital surgery. But despite my best efforts, it’s still high. I send a message to her surgical team, begging them to consider relaxing their stance on her glycemic control prior to surgery. At least she doesn’t have a cough.

Finally, it’s time for lunch. Except my next patient is in 10 minutes. The patient’s chief complaint is fever and cough for one week. Can I be on quarantine yet?

This crisis is infuriating, and frustrating, and frightening because my patients will disproportionately suffer, and there is little I can do to stop it. So, while everyone is home tomorrow, I will get up, cover up the dark circles, kiss my boys goodbye, and go to work.