Many British bosses keep quiet on Scottish independence—but secretly hope it doesn’t happen

Businesses hate uncertainty, we’re told, and sometimes threaten to relocate their headquarters in response to changes (or possible changes) in the law—taking jobs, tax revenue, and international prestige with them.

Businesses hate uncertainty, we’re told, and sometimes threaten to relocate their headquarters in response to changes (or possible changes) in the law—taking jobs, tax revenue, and international prestige with them.

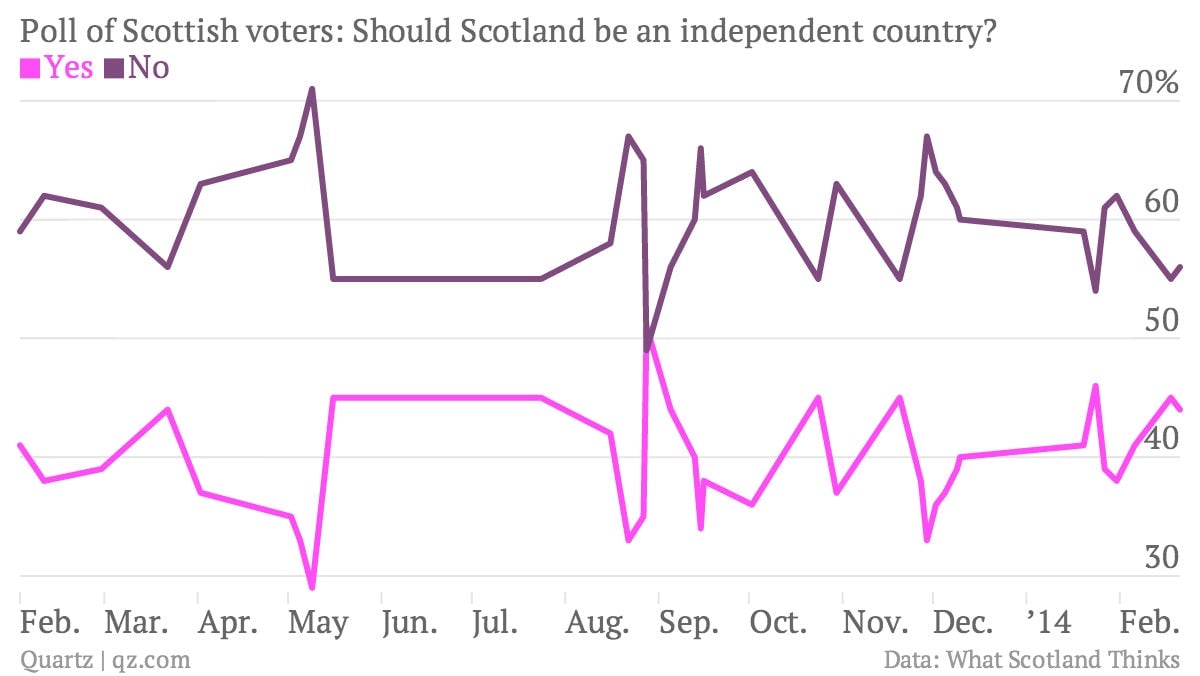

But what if instead of a company threatening to switch countries, it was the country that switched on the company? This is the question facing companies with operations in Scotland, where a referendum on independence will be held on Sep. 18. Although the “yes” camp is behind in the polls, the Scots declaring independence is a real enough possibility that some companies are quietly making plans.

Few company bosses have publicly revealed these plans so far, nor said much of anything about the vote, for fear of alienating customers on either side of the debate. But an anonymous survey of FTSE 100 chairmen earlier this week found that two-thirds thought an independent Scotland would be bad for business. After all, there is plenty of uncertainty hanging over an independent Scotland—its currency, EU membership status, and sovereign debt burden, for example.

Edinburgh-based insurer Standard Life recently gave the clearest account of any big British firm of its plans for potential Scottish independence. In a letter to shareholders (pdf), CEO David Nish noted that the company “started work to establish additional registered companies to operate outside Scotland, into which we could transfer parts of our operations if it was necessary to do so.” This was interpreted as a broadside against the pro-independence camp, despite the company’s “strict political neutrality,” as Nish described it.

For his part, RBS boss Ross McEwan has suggested that his bank hadn’t yet hatched a contingency plan, adding only that “we are neutral and won’t do anything to raise the temperature of that vote.”

Last week, Sam Laidlaw, CEO of utility group Centrica, was asked about the referendum on a conference call. “At the end of the day, this is a matter for the Scottish people,” he said, by way of preamble. He then listed several thorny areas in the oil, alternatives, and nuclear power sectors where official liabilities are not neatly split between the governments in the north and south. “These are going to be complicated issues that have to be worked through,” he noted, ominously.

The only major company boss to speak out candidly in recent weeks is Bob Dudley, chief executive of oil giant BP. Earlier this month, he fretted about the rise in costs that may result from a new border cutting across the company’s operations. “My personal view is Great Britain is great and it ought to stay together,” he added.

The candid views of “the American,” as US-born Dudley was often described in the British press, were passed off as the tactless musings of a foreigner. But according to recent surveys and executives’ famous fear of uncertainty, BP’s boss may be the only one brave enough to say what many of the others are thinking.