How Covid-19 could disrupt pharmaceutical supply chains

So far, the United States has reported only one drug shortage as a direct result of the Covid-19 pandemic. But the structure of the drug supply chain means the country could see more. And because of the secrecy built into the pharmaceutical supply chain to protect companies’ trade secrets, it’s hard for regulators and public health officials to figure out exactly what drugs may be hard to come by, and when.

So far, the United States has reported only one drug shortage as a direct result of the Covid-19 pandemic. But the structure of the drug supply chain means the country could see more. And because of the secrecy built into the pharmaceutical supply chain to protect companies’ trade secrets, it’s hard for regulators and public health officials to figure out exactly what drugs may be hard to come by, and when.

To start to understand those dynamics, we have to start at the source: The drug manufacturing plants located all over the world.

“When you get a bottle of drug, and it has Pfizer’s name on it, it doesn’t mean that Pfizer makes that product,” says Erin Fox, a professor of pharmacotherapy at the University of Utah and expert on drug shortages. The drug company on a prescription bottle is merely the party that is selling you the medication. “Lots of drug companies hire other companies to make the drugs for them.”

About 90% of all active pharmaceutical ingredients, or APIs, are made outside the US, according to a 2019 paper published in the National Bureau of Economic Research. And once a factory makes a drug’s API, that product may be shipped to another company to make the actual drug. Per the NBER, about 60% of these secondary companies are also outside the US.

Based on the FDA’s records, the US has nearly 4,000 manufacturing plants that either make APIs, drugs, or both—the most in the world. But China and India have the second and third most, at 634 and 639 respectively. All of these countries have been hit heavily by Covid-19, and it’s not clear how production of specific drugs has been disrupted—if at all.

Why is that so difficult to know? While the FDA keeps a list of these manufacturers, it doesn’t require them to say what they make; that information is considered proprietary.

Importantly, manufacturing companies are usually tasked with meeting long-term demand projections. They do what pharmaceutical companies tell them to—which is usually make a certain amount of a drug based on the demand over the last five years or so. This quantity doesn’t account easily for global emergencies that may dramatically accelerate demand.

Distribution, large and small

Drug companies with patented medications have exclusive rights to make those products; instead of manufacturing those abroad, they may choose to import the APIs and manufacture the drugs themselves. But even so, they have to go elsewhere for the next step in the process—distribution.

Once these drugs are finished, they’re shipped off to wholesale distributors. In the US, that’s likely one of three main companies: AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson. These companies organize all the drugs for distribution in the US, store them in times of need, and may even buy them back when there’s less demand for them.

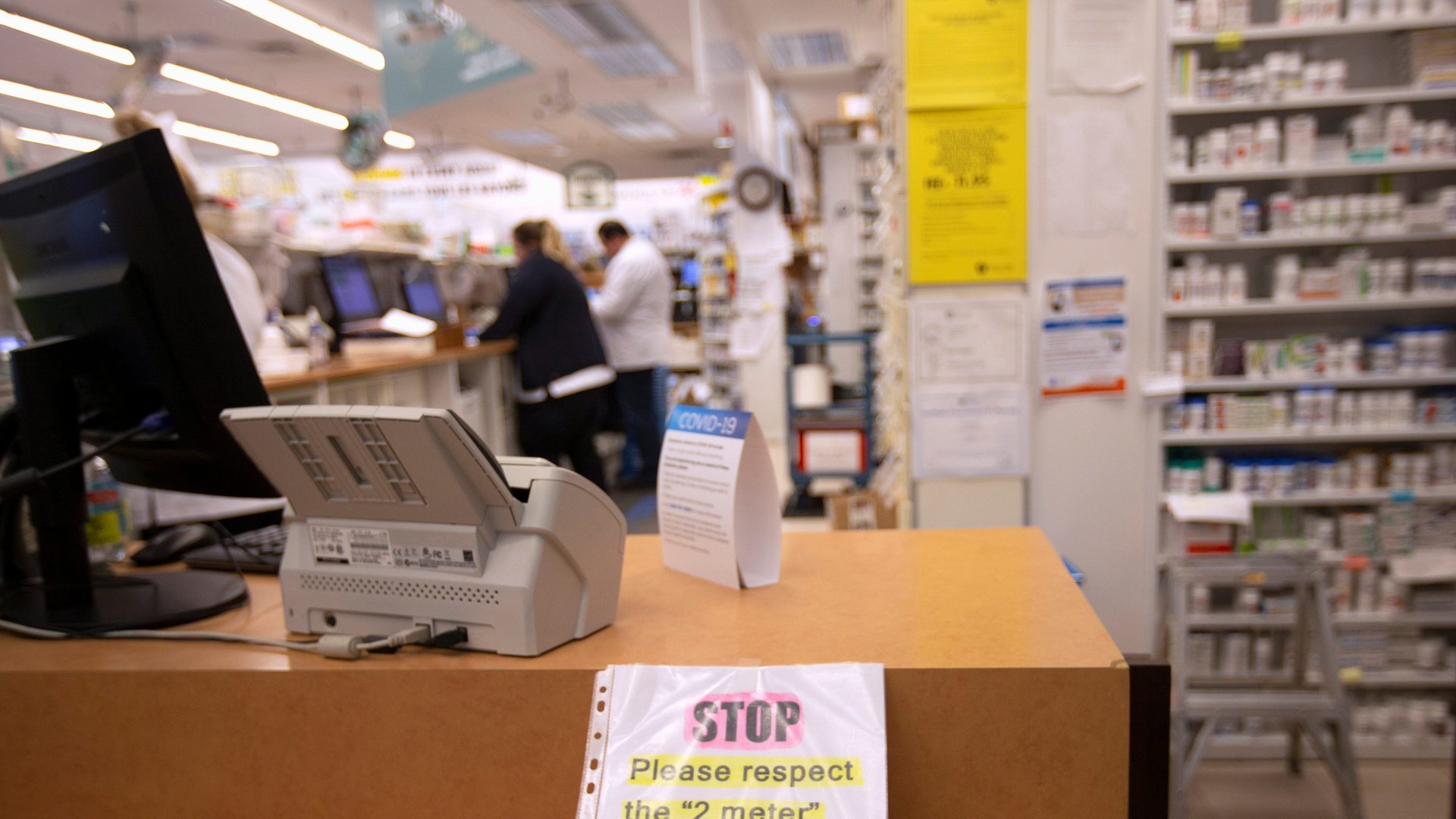

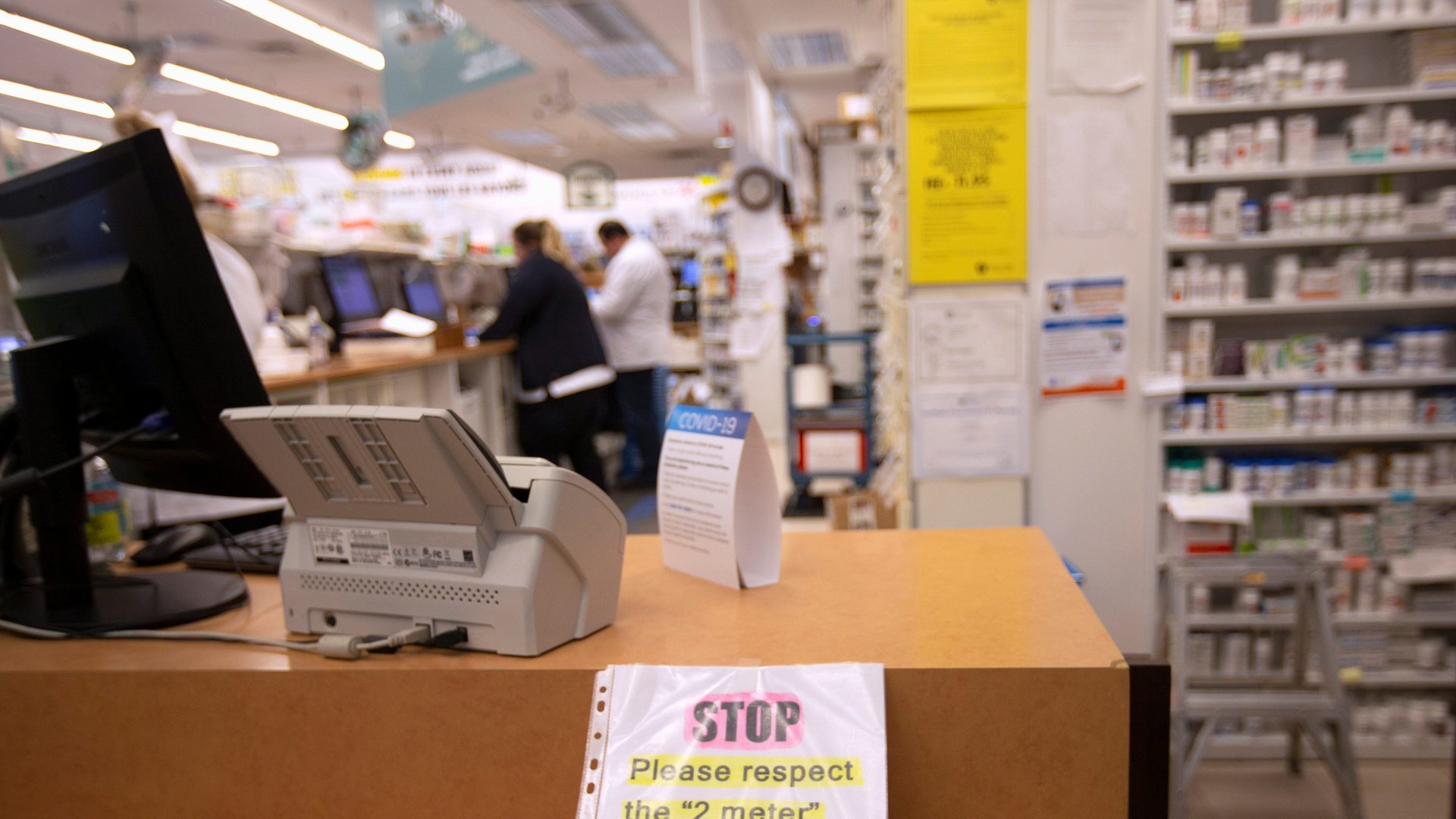

Wholesalers ship drugs to pharmacies—which is technically anywhere that drugs are dispensed to people. Most people in the US receive their medications from a pharmacy in their neighborhood, or in the hospital, but some pharmacies can send medications through mail orders, or operate out of long-term care facilities.

If there’s high demand for a drug, it’s up to pharmacists at each of those locations to fill it by contacting the wholesalers. But if there is a shortage, wholesalers work to distribute what they have across different pharmacies equally, so that every location has the same amount.

So what does this mean for getting your drugs?

It’s difficult to say.

In late February, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—which keeps an official tally of drug shortages based on manufacturers’ reports—identified 20 drugs at risk of going into shortage whose active pharmaceutical ingredients are made in China. So far, only one of those drugs, which was not named in the press announcement, is in short supply, but the agency also noted that there are alternatives doctors can use for patients in need.

Drug shortages are a regular occurrence—there’s almost always a running list—so not all of the 147 drugs currently in shortage in the US are related to the pandemic. Some existed ahead of time, and others are a result of shifts in the market.

The FDA isn’t the only source of information on shortages. According to the American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists, some hospitals are already reporting shortages of some drugs used to keep people on ventilators or to open up airways. But again, this doesn’t mean that patients are out of luck—in most cases pharmacists and other health care providers can come up with workarounds for these shortages. If one drug isn’t available, there’s likely a similar one that can do the job for any given patient.

The US Centers for Disease Control recommends that consumers keep an extra short-term supply of their own daily prescriptions in the event of an emergency (like a pandemic), but it doesn’t say for how long. The good news, Fox says, is that medications in pill form—which make up the majority of at-home drugs—are relatively easy to make, compared to hospital drugs. So even if there is a shortage, it hopefully won’t be for long.