To combat coronavirus, states are relearning lessons from the climate fight

As the coronavirus pandemic broke over American shores in January, the federal government was missing in action. President Donald Trump promised in February the coronavirus would “miraculously” go away despite grim evidence piling up in hospitals and ICUs around the world. By the time the administration curtailed travel from China and then Europe, an epidemic was already spreading undetected in the US.

As the coronavirus pandemic broke over American shores in January, the federal government was missing in action. President Donald Trump promised in February the coronavirus would “miraculously” go away despite grim evidence piling up in hospitals and ICUs around the world. By the time the administration curtailed travel from China and then Europe, an epidemic was already spreading undetected in the US.

Since then, conflicting guidance, a Darwinian procurement process for life-saving medical supplies, and federal commandeering of medical supplies destined for states have only reinforced the sense that no one is really in charge in the US. “How confident am I of federal responsibility and action?” asked New York’s governor Andrew Cuomo on April 9. “Not that confident.” The US now has the highest death count from the coronavirus in the world.

The federal government’s response to the coronavirus is the opposite of what America’s founders intended, says Stanford University law professor Richard Thompson Ford. The founders’ original worry was that weak local governments would fail to confront threats and protect the public under the influence of special interests. A centralized federal government was envisioned as a counterweight to bad governance and remedy to the “mischief of faction,” wrote James Madison in the Federalist Papers.

Yet the opposite has happened.

“Today, the worst fears of the founders have been realized, but often the roles are reversed,” writes Ford. “The threat comes from the highest levels of the extended sphere. Meanwhile, hope of redemption lives in the humble public servants of our city and county government.”

It’s a lesson climate advocates learned more than a decade ago.

The Feds are not coming to the rescue

Federal agencies, usually at the forefront of a natural disaster, have receded during the coronavirus pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention bungled the first coronavirus test and failed to ramp up testing. The agency has since offered inconsistent guidance for healthcare workers and the public and stopped holding media briefings.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency, conspicuously absent during the initial stages of the outbreak, is now ordering medical supplies. But Trump had announced on March 16 that if states need personal protective equipment, “they can get them faster by getting them on their own.” States that did so are now complaining the federal government is diverting their orders.

Working at cross purposes to the federal government is nothing new for those on the front lines of the climate fight. The US has no formal climate policy. Since the US refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, the world’s first international climate pact, in 2001, no major climate legislation has been passed by Congress—no comprehensive strategy to cut emissions for agencies from the Department of Energy to the Environmental Protection Agency.

According to Carla Frisch of the nonprofit Rocky Mountain Institute, states and cities have learned how to step into the void on climate change. “The center of gravity for climate action has been state and city governments and corporations over the last three years,” she says.

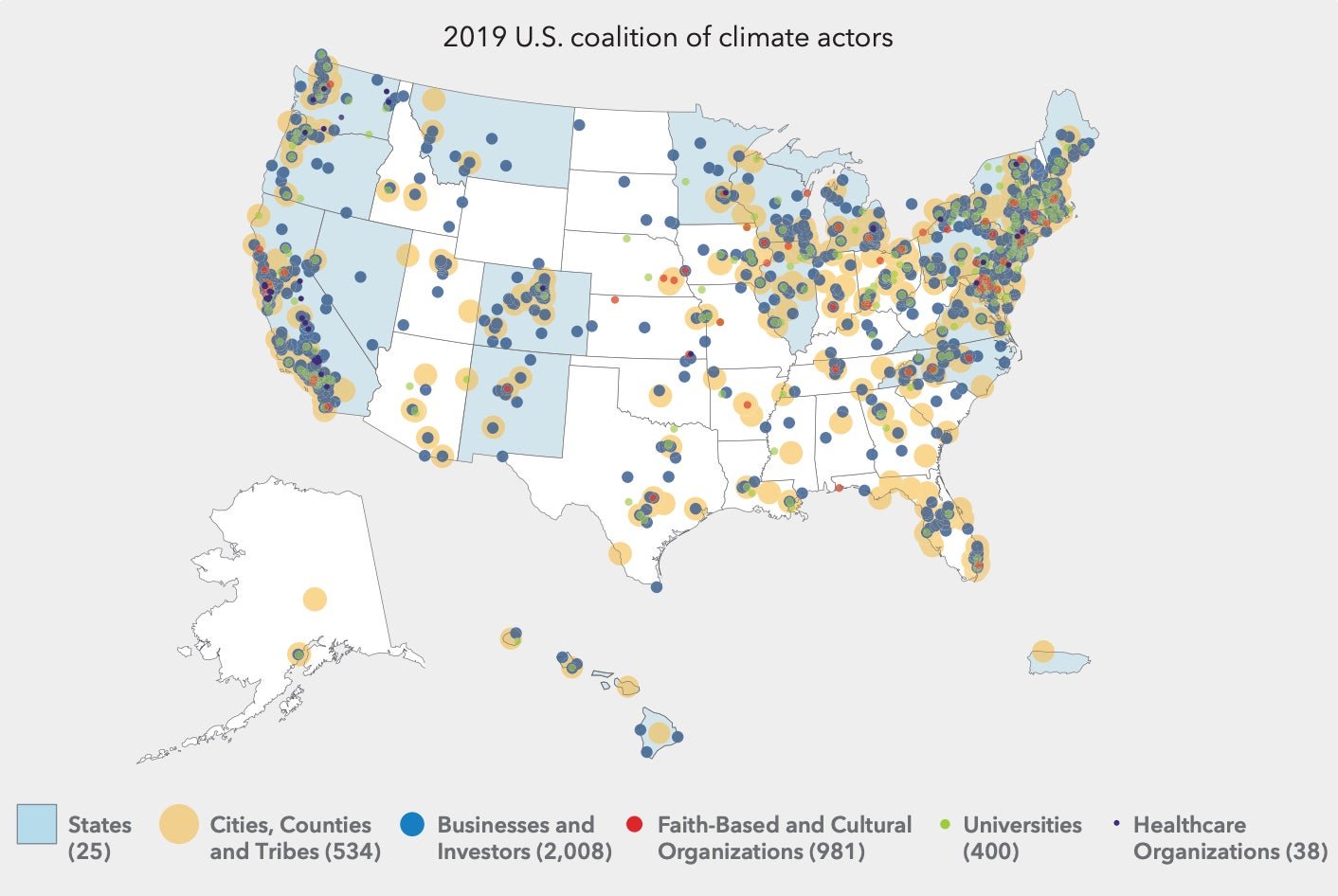

Since Trump announced his intention to withdraw the US from the Paris climate accords in 2017, sub-national actors from cities to states to Native American authorities have assumed the mantle of the accords. More than 13 states now have 100% renewable or zero-carbon emission goals by or before 2050. At least 177 US cities now have public emission commitments representing 51% of US emissions—and nearly 70% of the US GDP. If considered as a single country with climate targets, these subnational entities would be second only to the US itself as the world’s largest economy.

Those commitments add up. By the end of the decade, measures already on the books would reduce emissions 25% below 2005 levels (pdf). That’s not far off the goal the US committed to in 2016 (pdf) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 26% by 2025.

Coronavirus actions

States are walking a similar path with coronavirus. Within three months, states have gone far beyond federal guidance, enacted strong unilateral measures, and formed multi-state pacts to combat the virus. States have forcibly rejected calls to reopen on a federal timeline despite Trump’s false insistence he has “ultimate authority” over the states.

On the East coast, governors in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut began coordinating a regional response against the coronavirus. Four other states later joined to lift movement restrictions without triggering a new outbreak. “New York is partnering with these five states to create a multi-state council that will come up with a framework based on science and data to gradually ease the stay at home restrictions and get our economy back up and running,” said New York Governor Andrew Cuomo in a statement.

The same dynamic has emerged on the West coast. After receiving an inadequate 1 million medical masks from the federal government, California governor Gavin Newsom announced on April 7 he would use the state’s purchasing power as the world’s fifth-largest economy to procure needed supplies. “We’ve been competing against other states, against other nations, against our own federal government for PPE—coveralls, masks, shields, N95 masks—and we’re not waiting around any longer,” Newsom said on MSNBC. The state has reportedly signed a $1 billion contract for more than 200 million masks per month, enough to meet its needs and those of some neighboring states.

A “Western States Pact” including California, Oregon, and Washington has followed for the state to act “in close coordination and collaboration to ensure the virus can never spread wildly in our communities.” The move establishes common principles for when the three states will begin lifting restrictions and reopening their economies, a move Newsom promised would be guided by “science and public health, not politics.”

Together, the two coalitions cover 107 million people, almost a third of the US population.

All for one is still better

Yet state actions can’t make up for the absence of a unified federal response. At best, it’s a stopgap measure. For the climate, a federal commitment would enable roughly twice the emission cuts (pdf) as subnational measures alone, estimates Bloomberg Philanthropies. Achieving a net-zero economy by 2050 (what’s needed to keep global warming below 1.5°C) is virtually impossible without it.

In the coronavirus outbreak, a fragmented response means one lax jurisdiction can spark infections in another despite early progress. Outbreaks in states refusing to act, such as South Dakota (now home to one of the biggest coronavirus clusters in the country), risk spilling over into neighboring states.

If this is a wartime effort, as Trump has called it, then it’s one being fought against a chaotic, indifferent, sometimes hostile White House as much as the virus itself. That’s left state leaders treading a thin line. They must chart their own course to protect their citizens from the virus, and secure federal assistance even when it defies Trump’s wishes or demands.

But a template for state leaders exists. The US is rare among countries for the power given to states and cities to govern their own residents under a federalist constitution. In fact, it wasn’t long ago that Americans described their nation in plural—”the United States are”—before embracing a singular “the United States is” during the early twentieth century. The pandemic means states are once again in the lead role at a time the federal government is faltering.

For those acting on climate, of course, the power has already moved to cities, states, and companies. Coalitions representing 65% of the US population and half of greenhouse gas emissions have agreed to cut emissions, struck international climate deals, and charted a path to fulfill America’s international commitments. The nation just needs to follow.