No economy “needs” inequality—it’s a political choice

Inequality is a choice, but it’s not one we have to make to grow.

Inequality is a choice, but it’s not one we have to make to grow.

That might sound obvious, but isn’t to economists. Most of them think there has to be a trade-off between equality and efficiency. That taxing the rich to give to the poor has to slow the economy down. Because rich and poor alike will have less incentive to work, so they won’t.

But, as you may have noticed, the world doesn’t always work the way economists think it has to. It turns out that redistribution might actually increase growth, at least within limits. That’s the conclusion of a new paper from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that looks at how inequality and redistribution affect how much and how long the economy grows. The trick is isolating how much redistribution helps growth by reducing inequality, and how much it hurts growth by reducing work incentives. But the researchers were able to do this by looking at Frederick Solt’s data on country’s inequality before and after taxes-and-transfers, and then running a few tests. Here are the big takeaways. (Note: The Gini index measures the income distribution on a scale from 0, where there’s perfect equality, to 100, where there’s perfect inequality).

1. If two countries have the same amount of redistribution, the one with more inequality will tend to grow less. Specifically, moving from the 50th to the 60th percentiles for inequality will knock 0.5 percentage points off of per capita growth a year.

2. If two countries have the same amount of inequality, the one with more redistribution will not tend to grow any less—at least not in a statistically significant way.

3. But this doesn’t tell us the whole story about redistribution and growth. That’s because redistribution doesn’t keep inequality constant; it reduces inequality. So what we really want to do is add these two together, to see the combined effects of less inequality and more redistribution on growth. Since the former helps growth and the latter doesn’t hurt it that means that redistribution overall tends to increase growth.

4. How long an economy grows, though, can be more important than how much it does. As the researchers point out, growth isn’t some linear process. It comes in fits and starts, and it can be hard to restart after a fit. The question then is what inequality and redistribution do to how long a “growth spell” lasts. The answer: pretty much the same thing they do to how much growth there is.

5. The more inequality there is, the greater the chance that a growth spell will end the next year. The researchers found that every point the Gini index goes up makes growth 6% more likely to stop soon.

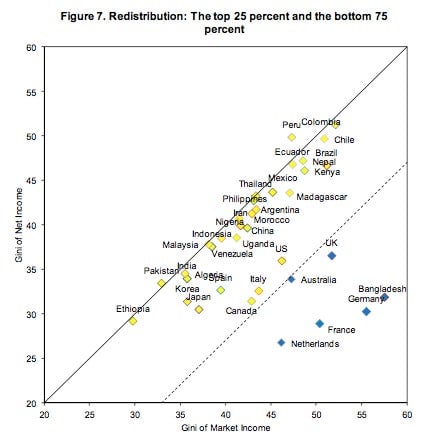

6. Redistribution has a more complicated relationship with growth spells. It doesn’t affect how long the economy grows when it’s low. But it does make the economy less likely to keep growing when it’s high, in the top 25%. You can see just how high is high in the blue dots below. The countries with the most post-tax equality—and redistribution—tend to be the most unequal pre-tax. In other words inequality is always and everywhere a political phenomenon. It’s a choice.

7. But, as I said before, it’s a choice we don’t have to make. Redistribution overall helps, and at least doesn’t harm, growth spells. That’s because the positive effects of less inequality add to or offset the negligible, or negative, effects of redistribution itself. When redistribution is in the bottom 75%, these positive effects are the only ones, and growth lasts longer. And when redistribution is in the top 25%, these positive effects make up for the negative ones from taxing-and-transferring so much—it’s a statistically insignificant wash.

So countries that spread the wealth around more seem to grow more and grow longer than countries that don’t.

***

Before we rush to raise tax rates to 90$, it’s important to remember that these are only correlations. They don’t tell us that redistribution is what’scausing better growth. Maybe governments that redistribute are also the kind that protect property rights, enforce contracts, and invest in infrastructure—and that’s what’s boosting growth. Then again, maybe it is the redistribution. Maybe giving everyone healthcare and an education makes them so much more productive that it overwhelms any disincentives. Or, as Ryan Avent points out, maybe redistribution makes it so people don’t need to take out risky loans, and that keeps growth from faltering.

There are plenty of plausible stories, but in a way, it doesn’t matter which one you believe. What does matter is there isn’t much evidence that we have to choose between a fair society and a dynamic one, that redistribution doesn’t preclude growth. And that our new Gilded Age doesn’t have to be one—if we choose.