China vows to keep economic growth steady—but what it really needs is a soft landing

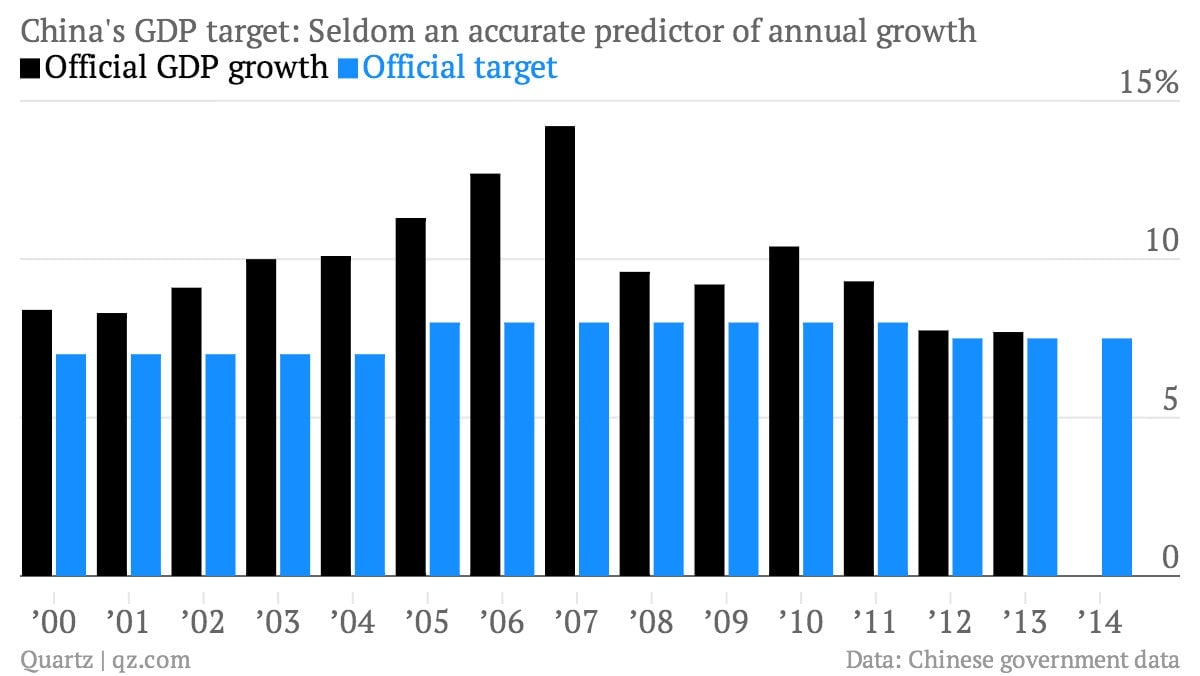

The world economy’s recovery might be faltering, but the Chinese government isn’t budging with its economic growth target. In the “work report” of the National People’s Congress today, Chinese premier Li Keqiang announced the country’s GDP will increase by 7.5% this year—the same target he set for 2013 and his predecessor, Wen Jiabao, set in 2012.

The world economy’s recovery might be faltering, but the Chinese government isn’t budging with its economic growth target. In the “work report” of the National People’s Congress today, Chinese premier Li Keqiang announced the country’s GDP will increase by 7.5% this year—the same target he set for 2013 and his predecessor, Wen Jiabao, set in 2012.

Does this mean the storm clouds are parting, and that the government’s commitment to propping up growth will usher the Chinese economy past its recent slowdown? Some observers think so (paywall). But Leland Miller, president of research firm China Beige Book International, disagrees.

“China is slowing down—period. The only question is whether the slowdown will be bullish or will be bearish for China,” says Miller. Despite the rosy 7.7% GDP growth China reported in 2013, CBB has tracked a steady slowdown across all sectors other than manufacturing throughout the year. Its research also shows that small- and medium-sized businesses aren’t getting the credit they need to grow, suggesting much of China’s surging credit growth is going toward rolling over old loans instead.

This is one huge reason China needs its economy to slow down: It needs to shift away from a reliance on credit-fueled, state-focused investment, and toward growth that is driven by consumption and private enterprise. Crucial to achieving this goal are the oft-discussed reforms broached in the third plenum in Nov. 2013, such as allowing the market to determine interest rates, launching deposit insurance, and widening the yuan’s trading band. The country’s ballooning debt makes this shift all the more urgent.

Many economists doubt it’s possible to transition the economy and implement reforms while still keeping the economy growing at 7.5%. One worry is that, by continuing to stimulate the economy in order to meet that target, the government will exacerbate problems like debt and excess capacity in industrial sectors.

Instead of paying too much attention to the 7.5% target, China-watchers should keep an eye trained on the government’s will to muscle through market reform, boost the service-sector’s share of the economy, and allow defaults to start happening—signaling that market risk, and not political risk, is being used to price credit. ”It’s really a question of… seeing if the government is implementing the type of reform program to have slower, healthier growth,” says Miller.

However, the balancing act will be fiendishly tricky, says Eswar Prasad, a professor at Cornell and former head of the IMF’s China division.

“These reforms are inherently risky. Even if they’re trying to do the right thing, it could end up creating very substantial risks in the process of undertaking the reforms—and they can’t let growth slow too much during the process,” says Prasad. ”The next two to three years are going to be crucial because, in that window, if they don’t manage to make this transformation and put in place reforms, then they’ll be left an additional stack of problems.”