The four charts Vladimir Putin should consider as he plots his next move in Ukraine

Vladimir Putin put the Russian invasion of Ukraine on “pause” at a press conference on Tuesday, and markets stepped back from the ledge. The rout in Russian assets was partly reversed; the ruble regained some ground, as did stocks and bonds. As long as there isn’t any shooting—aside from the odd warning shot—the mood seems to be one of cautious relief.

Vladimir Putin put the Russian invasion of Ukraine on “pause” at a press conference on Tuesday, and markets stepped back from the ledge. The rout in Russian assets was partly reversed; the ruble regained some ground, as did stocks and bonds. As long as there isn’t any shooting—aside from the odd warning shot—the mood seems to be one of cautious relief.

But don’t expect any meaningful money to pour back into Russia until the ultimate outcome of Ukraine’s crisis becomes clearer. Was Putin’s conciliatory tone a result of the market’s rebuke? Perhaps, but that is probably a simplistic reading of the intrigue over the past few days, as purportedly stateless soldiers flooded into Crimea and issued mysterious ultimatums to local military units. Equally, Putin could be testing the markets and gauging whether it is worth his while to fight in the open instead of in the shadows.

Who will blink first?

On this point, it is useful to assess Russia’s economic options in case its military ones are activated in Ukraine. The mere threat of Western sanctions could be enough to defuse the situation, with the turmoil at the start of the week a preview of the pain that the markets can inflict. At the same time, Russia may calculate that it can withstand the turbulence longer than the West—more specifically that its energy users, banks, and others entities reliant on Russia’s physical and financial resources can hold their nerve.

As it happens, the last time Russia invaded one of its neighbors, it faced a severe financial crisis. But the Russian tanks rolling into Georgia was only one of the factors that battered markets in 2008, as the global financial crisis also hit the country hard. Is it better prepared this time around? Judge for yourself, as the charts below compare the Russian economy around the time of the invasion of Georgia with the situation today, starting from when protests kicked off in Kiev in November.

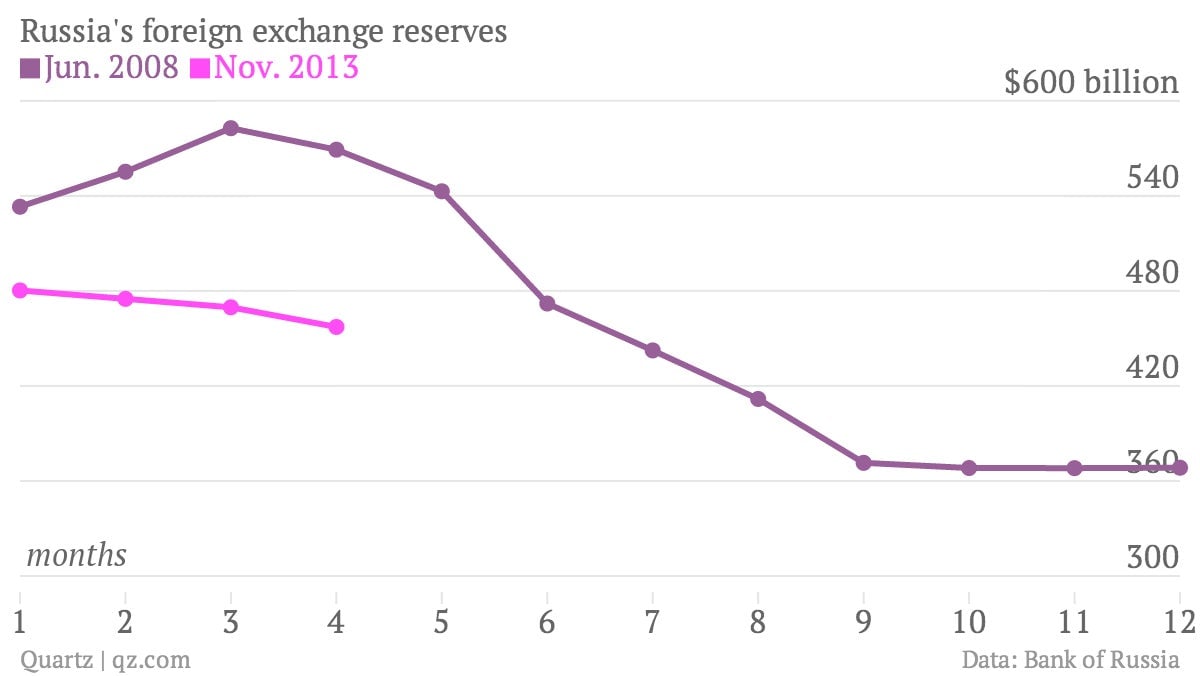

Foreign currency reserves

As the ruble tanked on Monday, Russia’s central bank hiked interest rates and spent more than $11 billion propping up the currency in the open market. It has quadrupled the amount it is authorized to spend to keep the ruble trading within its target range. If the currency comes under renewed pressure, future interventions will drain Russia’s foreign exchange reserves (which include some of the assets held in its two sovereign wealth funds, the Reserve Fund and the National Wealth Fund). Compared with 2008, Russia is starting from a somewhat smaller base of reserves to draw on, meaning it has less firepower with which to defend the ruble. In the tumultuous 12 months from June 2008, Russia’s reserves fell by $165 billion, which would be worth nearly 40% of today’s reserves.

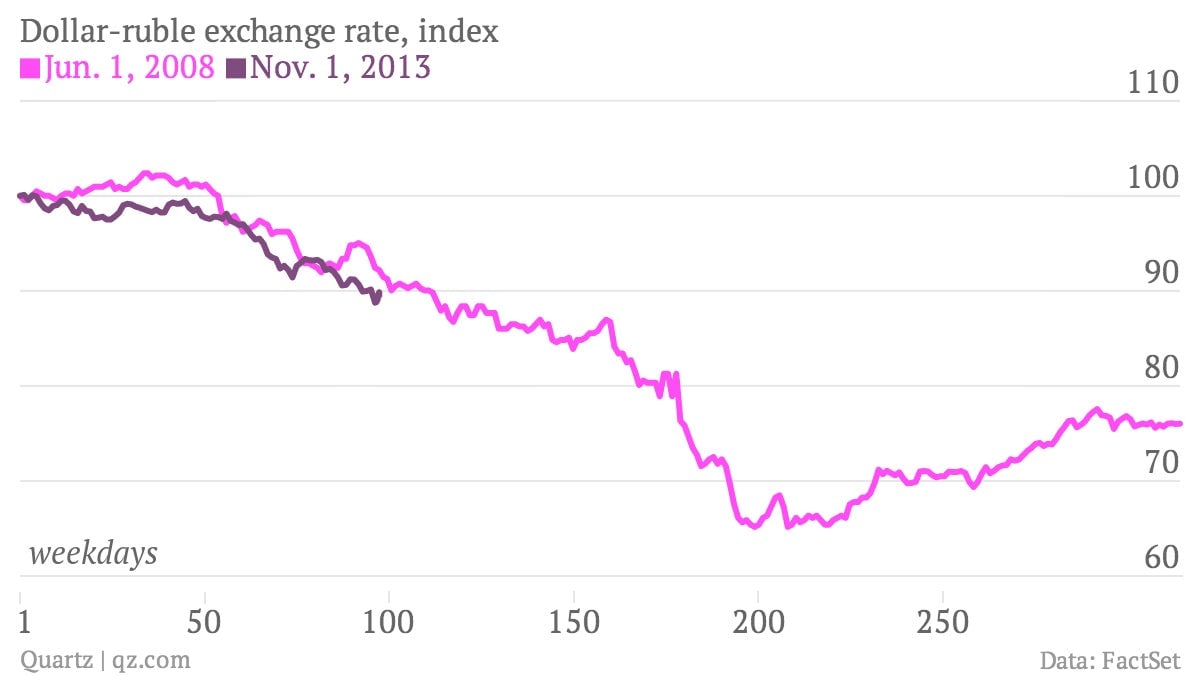

Currency values

Even before the latest bout of ruble turmoil, the Russian currency had been drifting downward for months, losing 10% of its value against the dollar since November. Thus far, it is following a similar path to mid-2008, although to see a depreciation on the same scale it would need to shed another 20% of its value in the coming months, which will depend on how aggressively the central bank deploys its reserves in defense the currency.

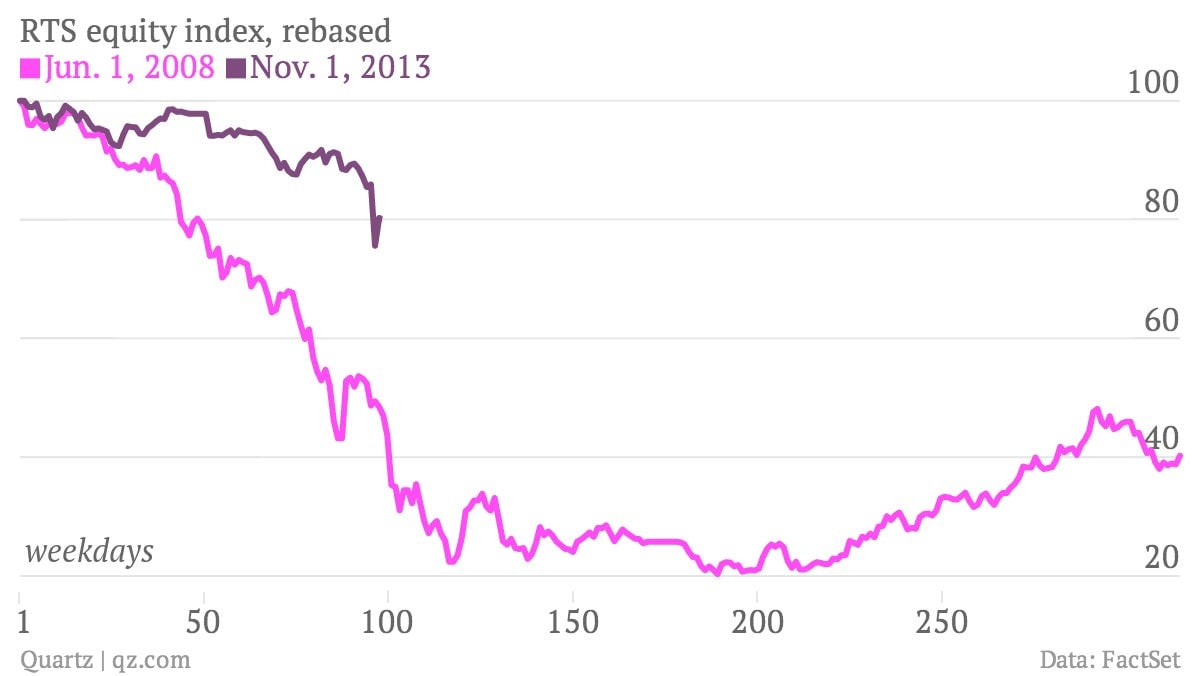

Stock markets

Compared with 2008, investors have been much kinder to Russian stocks, even considering the double-digit percentage plunge at the start of the week. Unlike the ruble, the benchmark RTS equity index has not regained as much ground as it lost on that day, but stocks aren’t yet under nearly as much pressure as they were during late 2008 and early 2009. Some think the declines are overdone and now is the time to buy.

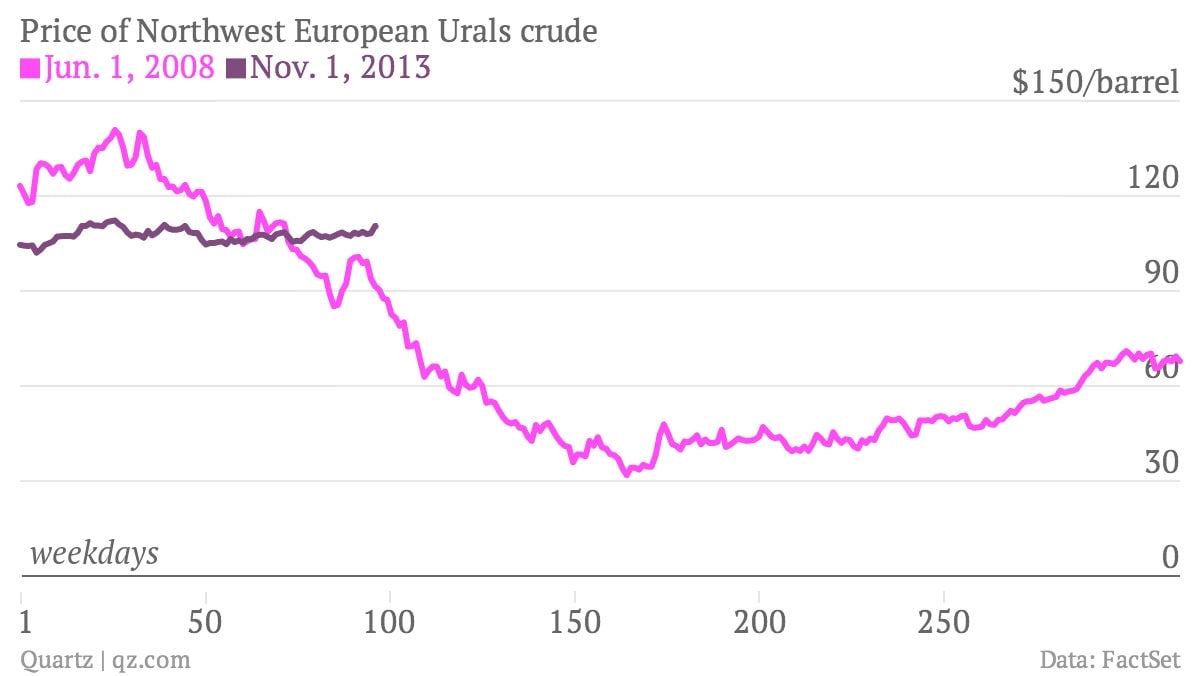

Energy markets

Another factor working in Russia’s favor is energy prices. The price of oil has been much more stable in recent months than it was during the turmoil of 2008; few expect it to plunge like it did back then, thanks to firmer demand from a global economy on the mend instead of one in the throes of the worst downturn since the Great Depression. Russia links its gas prices to oil, so this should support the energy exports on which its budget depends.

Much has been written about Europe’s reliance on the gas Russia pipes through Ukraine, not least how a mild winter has bolstered the continent’s gas inventories, making the threat of a disruption in supply less immediately daunting—and thus a less attractive weapon for Russia to deploy. European gas prices remain above last week’s levels, but for the most part countries that rely on Russian gas aren’t as exposed as they were when Putin last turned off the taps, in January 2009.

For Russia, its economic experience around that time is also something it would probably not want to repeat—in 2009 GDP sank by nearly 8%, unemployment spiked, and inflation ran in the double digits. And even as its economy has recovered, Russia is having trouble attracting investment and convincing its citizens to keep their money within the country. Provoking a return to recession—spurred by a currency collapse, sanctions, or some other Crimea-related shock—seems an unwise move.

Your move, Moscow

Of course, all wisdom is relative when geopolitics are involved. Some saw Putin’s press conference not as the performance of a cagey chess player but as a dangerous, out-of-touch rogue who was “nervous, angry, cornered, and paranoid, periodically illuminated by flashes of his own righteousness,” as one Russia watcher put it.

As the above shows, Russia is in some ways in better shape than it was in the run-up to its last financial crisis, but in others it looks like it may have already started retracing its previous path down into the doldrums. To the extent that things like foreign currency reserves and stock valuations play into the decision to invade a neighboring country, there is plenty for Putin to consider.