US hospitals are going to crazy lengths to get masks

The story sounds more like the set-up to a drug deal than an effort to secure critical medical supplies. It involves a flight out to a small airport near an industrial warehouse, disguised semi-trailer trucks, and agents from the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

The story sounds more like the set-up to a drug deal than an effort to secure critical medical supplies. It involves a flight out to a small airport near an industrial warehouse, disguised semi-trailer trucks, and agents from the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

But it’s actually the account of one hospital executive, published in a letter on the website of the New England Journal of Medicine yesterday, describing how his team was forced to get a supply of N95 respirator masks and surgical masks. It illustrates the extreme lengths US health systems are going to in order to overcome the critical shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) they face amid the Covid-19 outbreak.

In his account, Andrew Artenstein, chief physician executive at Baystate Health in Massachusetts, explained how challenging it has become to get medical supplies such as gowns, gloves, face masks, goggles, and face shields. The undersupply of PPE has resulted in a free-for-all where everyone from hospitals to the federal government is competing for shipments. At Baystate Health, the supply-chain group has “adapted to a new normal, exploring every lead, no matter how unusual,” Artenstein wrote. “Deals, some bizarre and convoluted, and many involving large sums of money, have dissolved at the last minute when we were outbid or outmuscled, sometimes by the federal government.”

The team got a lead on a shipment of N95 and surgical masks from China. Since scammers and price gougers have become rampant in the medical-equipment market, they got samples beforehand to ensure the N95 masks were up to standard. The order would cost more than five times what they would normally pay for a similar shipment, Artenstein noted, but less than what other brokers have asked. Satisfied with the product, they proceeded, going to great trouble to make sure their supplies wouldn’t be intercepted:

Three members of the supply-chain team and a fit tester were flown to a small airport near an industrial warehouse in the mid-Atlantic region. I arrived by car to make the final call on whether to execute the deal. Two semi-trailer trucks, cleverly marked as food-service vehicles, met us at the warehouse. When fully loaded, the trucks would take two distinct routes back to Massachusetts to minimize the chances that their contents would be detained or redirected.

Before the team could wire payment to the seller, two FBI agents arrived and questioned them, according to Artenstein. They were able to assure the agents nothing illegal was happening and were allowed to take their supplies. But Artenstein said he soon discovered the Department of Homeland Security was considering redirecting their shipment elsewhere. Artenstein made some calls that he said got a congressional representative involved and kept the supplies from being seized.

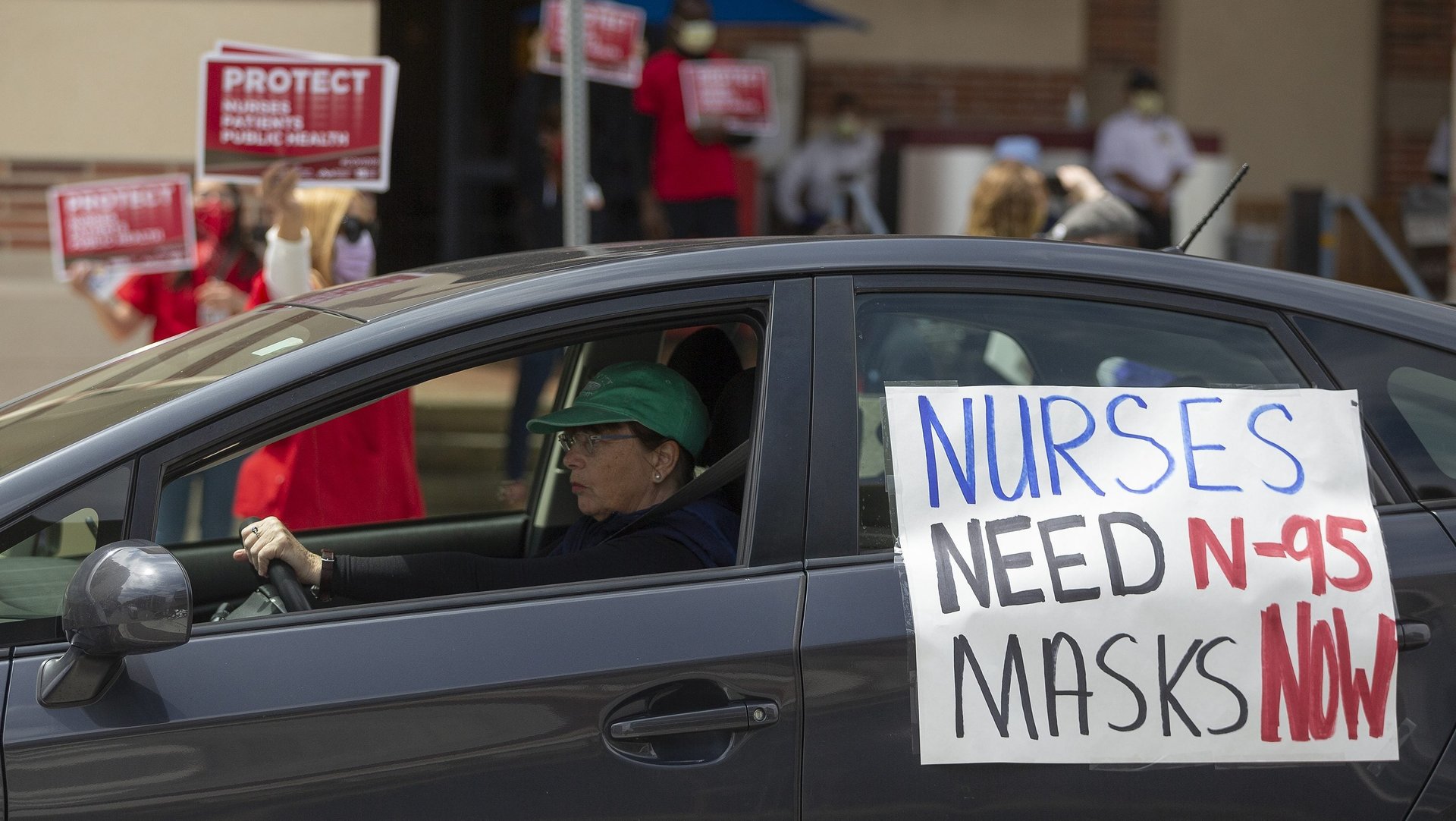

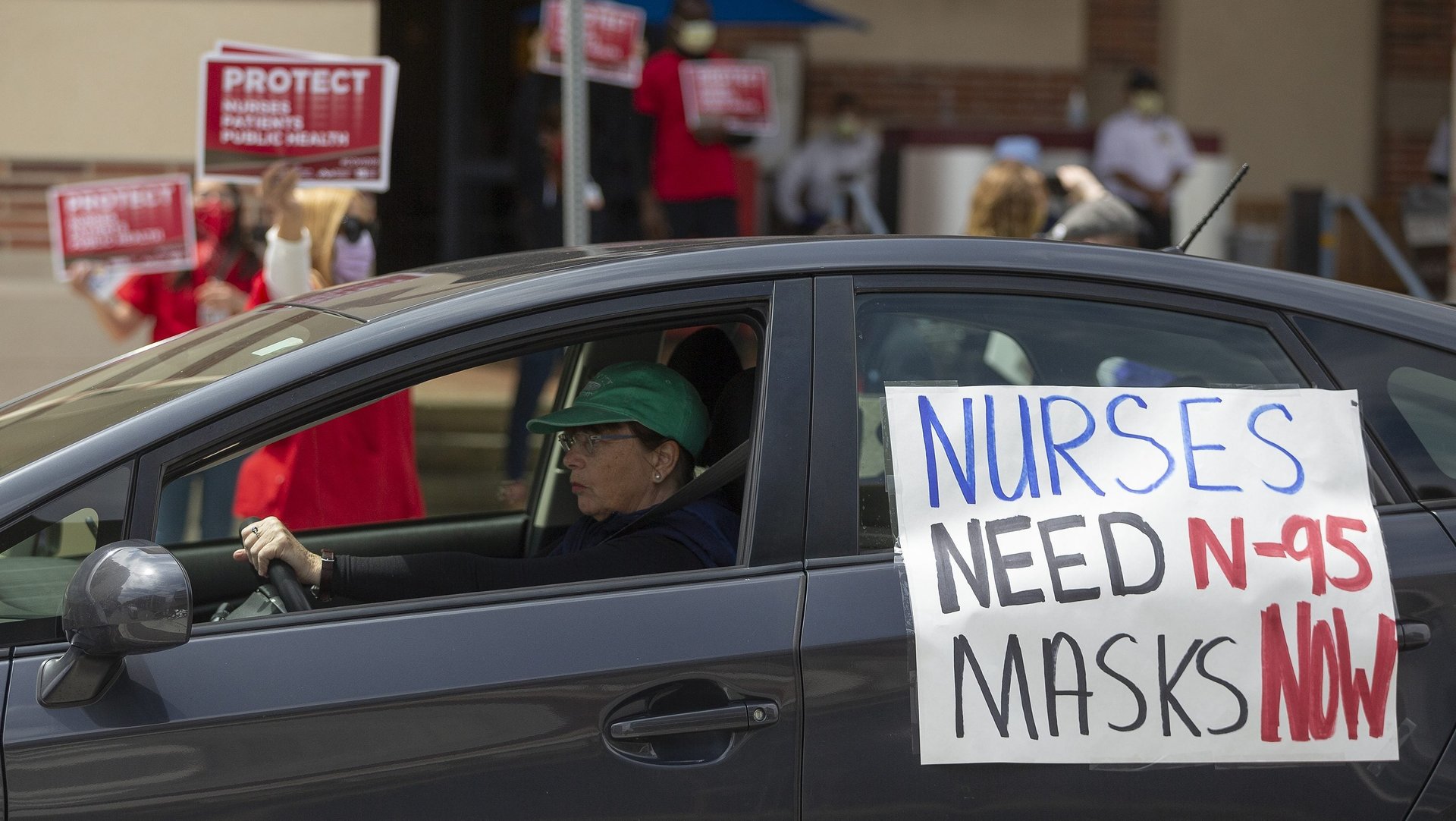

As dramatic as the story is, it reflects the challenges of many health and hospital networks in the US. The strategic stockpile of medical equipment available to the US wasn’t nearly sufficient to meet demand in a pandemic. As of April 2, it had distributed 11.6 million N95 respirators and 26 million surgical masks, and by that point was nearly depleted. About a week later, the Center for Health Security at Johns Hopkins University estimated that (pdf) the US will need about 136 million N95 or other disposable respirators and 360 million medical-grade masks.

Companies of all sorts, from medical suppliers to apparel makers, are churning out masks as quickly as possible, but they’re not simple to produce and most of the infrastructure to make them is located in China. Meanwhile, everyone in need of masks is left fighting to get their hands on shipments where they can.

“Did I foresee, as a health-system leader working in a rich, highly developed country with state-of-the-art science and technology and incredible talent, that my organization would ever be faced with such a set of circumstances? Of course not,” Artenstein wrote. “This is the unfortunate reality we face in the time of Covid-19.”