Humidity plays a role in seasonal spread of viruses. Will the same go for Covid-19?

It’s a mystery that has bothered scientists for decades: Why do temperate climates have a flu season? They’ve floated many theories, from a drop in vitamin D levels to people spending more time around each other indoors.

It’s a mystery that has bothered scientists for decades: Why do temperate climates have a flu season? They’ve floated many theories, from a drop in vitamin D levels to people spending more time around each other indoors.

According to a review study published last month in the Annual Review of Virology, indoor humidity may play a surprising role.

“Dry air is a key factor that impairs a person’s ability to fight off respiratory viral infections,” says Akiko Iwasaki, an immunobiology professor at the Yale School of Medicine whose research group assembled the review.

Viral seasonality is on more people’s minds than usual at the moment, since some public health experts predict that the novel coronavirus could return each winter, like the flu. “Unless we get this globally under control, there is a very good chance that it’ll assume a seasonal nature,” Anthony Fauci, the director of the United States’ National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said earlier this month. If that happens and before we have a treatment or vaccine for Covid-19, additional people will die every time the virus resurges, while survivors are kept in lockdowns and quarantines.

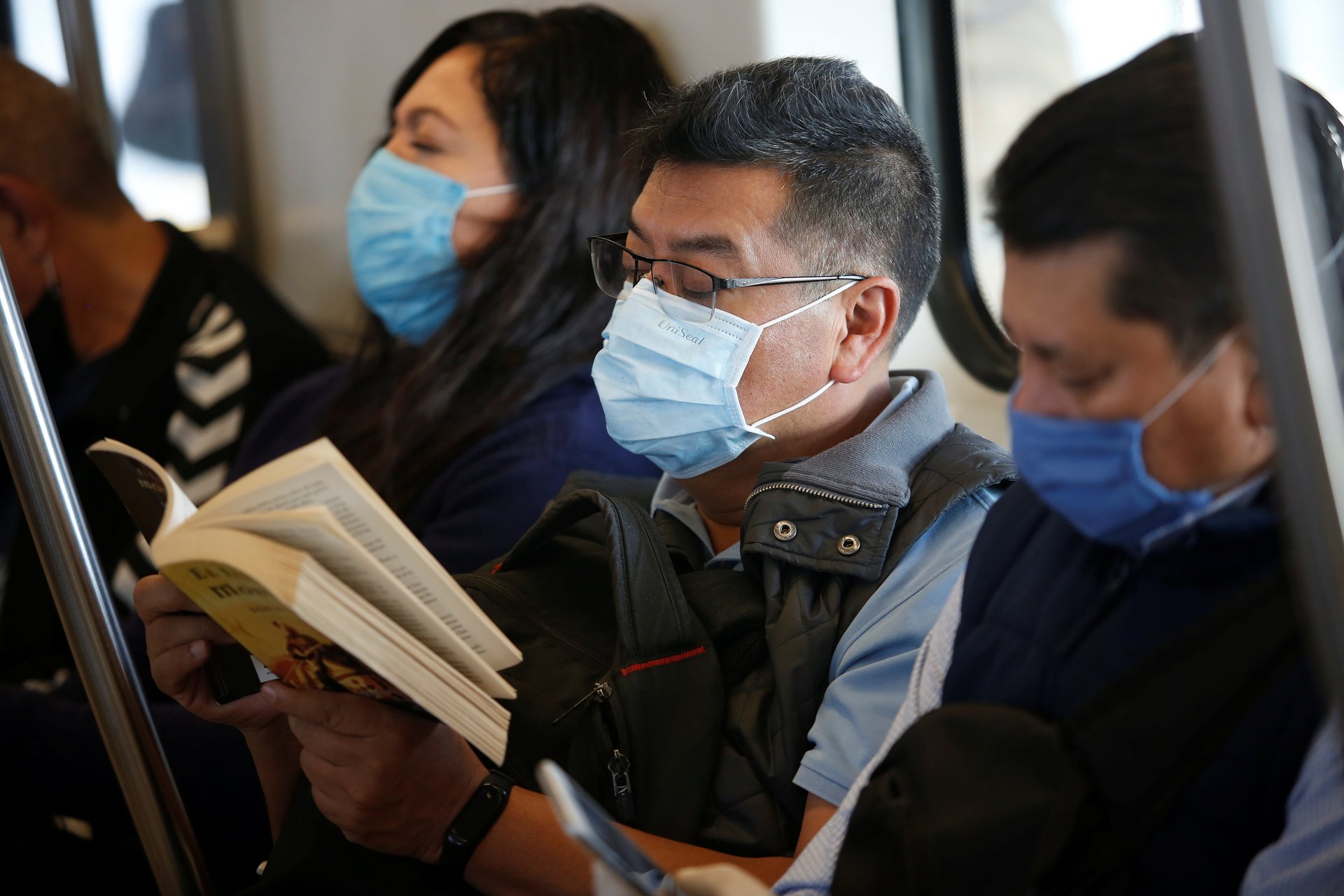

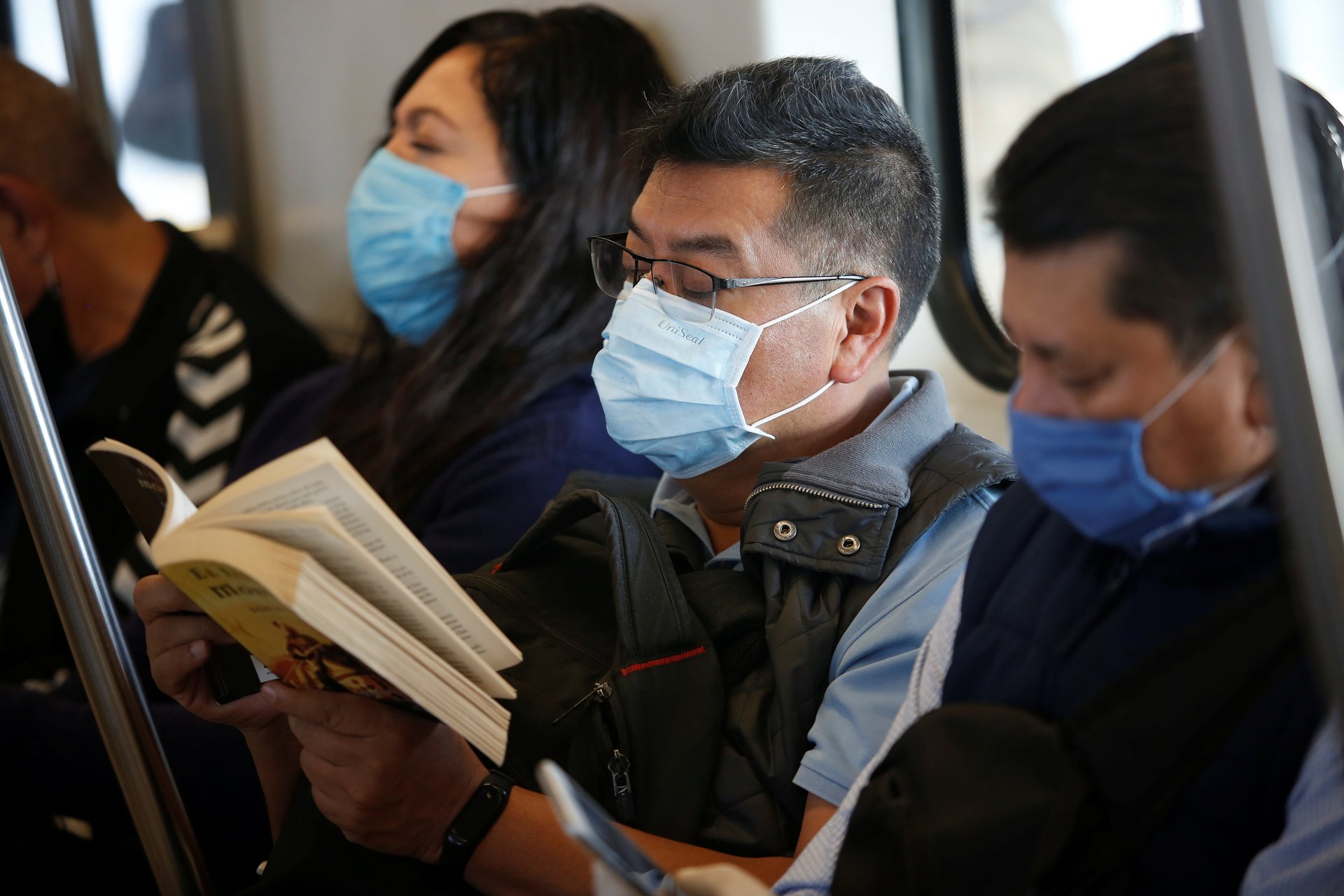

Several studies support the idea that indoor humidity plays a role in seasonal disease transmission. When someone coughs or sneezes, they release tiny droplets into the air (if they’re sick, these droplets will contain virus). The bigger droplets typically fall before they get very far, but the tiniest droplets, called droplet nuclei, can go much farther. In humid conditions, these tiny droplets don’t evaporate as much, so they drop down more quickly than they would in dry conditions. Virus-containing droplets that travel farther are more likely to infect a new host.

Low humidity also impairs the host’s ability to clear airborne viruses from their nose without getting infected, a fairly gross process of clearing snot from your nose (officially, it’s called mucociliary clearance).

“Not much attention is being paid to the quality of air indoors,” says Iwasaki, “which is really where we live our lives.” The review offers a hypothesis for how indoor humidity affects viral transmission, outlining both the physical process (the stability of viruses in a droplet, and their passage in the air as seen in animal models) and humidity’s effect on immunological responses.

While 40% to 60% relative humidity may be ideal to reduce viral transmission and infection in general, the Yale researchers suggest, previous studies suggest that indoor humidity in the winter months of temperate climates is below 25%—pretty much ideal for a virus looking to infect people with reduced defenses. Even without stay-at-home orders in place, people spend about 90% of their time indoors, so it’s unlikely that simply spending more time inside contributes substantially to an increase in winter flu cases.

But the relationship between viral seasonality and humidity isn’t one-to-one: In tropical regions, the flu season often aligns with the rainy season. “It’d be nice if we could come up with a single hypothesis, a single explanation that covers tropical and temperate regions,” says Linsey Marr, an engineering professor at Virginia Tech.

And it’s still too early to know what the results of this study might mean for the novel coronavirus that causes Covid-19. “This [study] talks about other coronaviruses that have been around for a while. And when there’s new viruses, all bets are off with regard to seasonality,” says Marr. “As the virus becomes more widespread, as more people are exposed, I could see it settling into a pattern typical of coronaviruses, which are more prevalent during the wintertime.”

As the study notes, researchers may have a better sense in the coming months. “The precise relationship between temperature, humidity, and Covid-19 will become more evident as the Northern Hemisphere reaches the summer months,” the authors write.

To help researchers understand how big a role relative humidity plays in disease transmission, says Marr, “we need more controlled studies both in animals and humans.” Animal studies allow researchers to control aspects of the environment that would be too challenging (or unethical) to do with humans. “There have been separate studies looking at just transmission at different temperatures and humidities,” she says. “We need to collect samples of the droplets containing viruses and see how well the viruses survive.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the reason that tiny droplets travel farther under humid conditions. It’s because they don’t evaporate, not because they collect water from the air.