This chart proves that unions can’t offer job security anymore

In 2002, desperation and dwindling membership led the United Auto Workers (UAW) union to recruit folks like me: graduate students at Columbia. After all, we too are undervalued, exploited, and a left-leaning bunch.

In 2002, desperation and dwindling membership led the United Auto Workers (UAW) union to recruit folks like me: graduate students at Columbia. After all, we too are undervalued, exploited, and a left-leaning bunch.

Except I was in the economics department, which actually crunched the data on membership dues, taxes, and perks. We emerged feeling lukewarm on the prospects of membership—unlike other disciplines. A strange quirk of academic culture is how alliances are formed. Economists judge people based on their math ability: friendship is fine with a physicist, but not an English student. Political scientists are tolerated because they validate our belief that economics is the most important and difficult subject. (If economists are the Mean Girls of academia, political scientists are our Gretchen Wieners.)

In the end, our union movement died when Columbia successfully appealed the ruling that we could unionize in the first place (though it recently resurrected itself at New York University).

A few weeks ago, the auto-assembly workers at the Chattooga Volkswagen plant also voted against joining the UAW. That even autoworkers are rejecting the union designed for them speaks volumes about the problem with unions today, and the problem my department once had with the UAW: there is no economic incentive to join.

This is hardly the case historically. Once upon a time, manufacturing work was grueling and involved terrible, dangerous conditions. The physical nature of the work meant older employees needed protection and income when they couldn’t work anymore. Unions were instrumental in improving the lives of factory workers and gave them the security they needed.

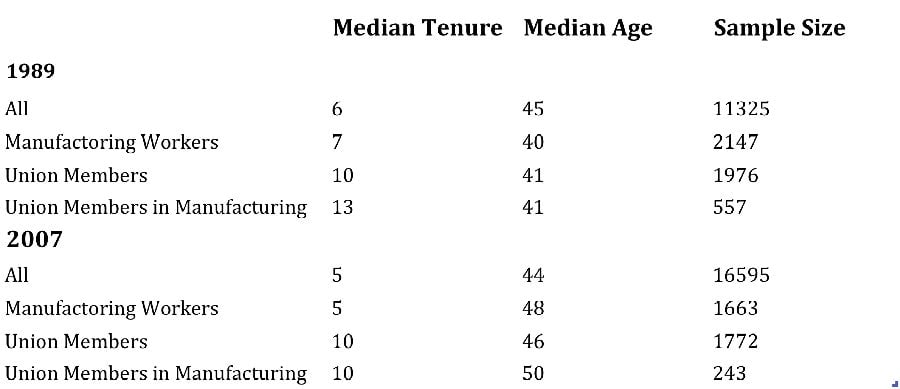

But times have changed and so have people’s economic interests. The first column of the table below shows the median number of years that survey respondents (from the US Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances) have worked at their current job. The second column is their median age. The data is broken down for manufacturing workers; union members; and unionized, manufacturing workers. The data is taken from two different years: 1989 and 2007 (2010 data is also available but more recent data reflects the recession, not just longer-term trends).

This chart reveals why joining a union is a bad idea. One of the biggest perks of union membership is job security. But people now spend fewer years at their job, even if they belong to a union. Consider that between 1989 and 2007, median tenure fell three years among union members who work in manufacturing industry. That is even more remarkable when you consider the typical unionized, manufacturing worker aged nine years. Normally as you age (especially in middle age) you gain more tenure; you’d expect an older population to have more tenure, not less.

Aging combined with falling (or constant, for the entire union population) tenure shows union members’ employment relationships have gotten shorter. It’s worth noting that union members still have longer tenure in their jobs compared to people with no affiliation, but some of that can be explained by age. It’s most telling how union members’ age and tenure have evolved since 1989. That might explain why union membership rates have taken a dive. In 1989, more than a quarter of manufacturing workers were members; in 2007 only 15% were (by 2010, it fell to 10%).

A large part of the perks unions provide, long-term job security and generous defined benefit pensions, is either non-existent or less valuable to modern autoworkers. Expensive retirement benefits are only valuable if you stay at the same company for many years; defined benefit plans aren’t worth much without decades of tenure.

Job tenure is down because unions can’t overcome the market forces that make jobs less secure: changing technology and globalization. Manufacturing work used to involve fairly routine tasks. Today, modern car manufacturing is extremely technical and has become more standardized across different car companies. The auto industry, especially auto-assembly, is one of biggest users of industrial robots. Robots have replaced many of the workers who did this job manually, but they also shift the demand to more skilled workers who compliment the robots. Meanwhile globalization has made the industry more competitive and several of the Chattanooga workers claimed they voted no to the union because they faulted UAW for making the American auto industry less competitive.

If you are a skilled worker in a competitive industry, job security may not be so valuable to you anyway. Skilled, technical workers often benefit from changing jobs regularly. If you work at several different firms you are exposed to different technologies and routines. The premium on having high-tech manufacturing skills has increased, which means these workers are in high demand. There are fewer of them. They are likely not unionized.

If even union members can’t count on their jobs like they used to, that undermines a large component of a union’s value. The benefits that remain may be not outweigh the dues and bureaucracy involved (which cuts further into their wages). Also as manufacturing workers become more skilled and specialized, autoworkers benefit less from bargaining through a third party that homogenizes them.

UAW contends politics, notably the Republicans in Tennessee, undermined its campaign and is appealing for another vote. But even if they win, they face an uphill battle. Unions once played an important and valuable role in American manufacturing. Perhaps they still can in the future. But the current structure and benefits of the UAW doesn’t make the sense for the modern autoworker. If unions hope to survive, they need to embrace the reality of the modern labor force, find a way to complement it, and upgrade the skills of their workers—and their own value proposition—in the process.