The US government’s coronavirus bailout is raising monopoly fears

As the US government works to rescue the economy from the coronavirus pandemic, watchdogs are keeping a wary eye on how those actions may change it over the long term.

As the US government works to rescue the economy from the coronavirus pandemic, watchdogs are keeping a wary eye on how those actions may change it over the long term.

“This money is going to have an enormous affect on the economy not just this month, but for years and years to come,” says Bharat Ramamurti, a former adviser to senator Elizabeth Warren and one of the five members of the Congressional Oversight Commission who will act as public watchdogs for the money.

Unlike the 2008 financial crisis, when the primary concern was rescuing banks that played a role in creating the problem in the first place, the concern today is making sure large corporations don’t unduly profit from the aid intended to keep people at work, and that they don’t use the rescue funds to drive smaller competitors out of business.

Judging by the stock market, investors expect the largest companies to be the winners in the pandemic economy. After all, they tend to have deeper capital reserves, better lobbying and banking connections, and often benefit from increased reliance on internet commerce while brick-and-mortar competitors languish without customers.

“If you pump trillions of dollars into big corporations right now, at the same time as small businesses across the country are failing, you’re going to see a massive increase in concentration across industries,” Ramamurti says.

Many economists worry that these dominant corporations would pose a threat to the economy, both in the near and long term.

For one, they say that the high unemployment resulting from the pandemic will decrease competition for workers, and that big businesses will use the opportunity to drive down wages and benefits. Some economists also believe that big businesses will slow innovation by blocking upstart competitors. Americans pay more than residents of other wealthy countries for everything from broadband internet access to healthcare in part because monopolies and cartels are able to exploit their market power and raise prices.

Amazon, as just one example, appears to have lied to regulators about using data garnered from companies that sell on its platform to steal their ideas and drive them out of business. App developers said in a January lawsuit that Facebook adopted similar tactics, and Congressional investigators are frustrated by the company’s attempts to assert it is not a major player in its market by including television, newspapers and video games among its competitors.

The White House doesn’t share these concerns. The Annual Economic Report of the President, published by the White House Council of Economic Advisers in February, argues instead that concentration has mostly benefitted consumers.

But Democratic lawmakers like Warren and House representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have proposed that the Federal Trade Commission block all mergers while businesses are still under severe financial distress. They’ve also asked the Federal Trade Commission to make rules about mergers that affect necessary healthcare equipment after the acquisition of a ventilator-manufacturer was tied to shortages of the critical machine in the US.

“People are under the mistaken assumption that one day the economy will go back quote-unquote to normal and everyone will go and get their old jobs back at the same wages,” Ramamurti says. “You’re going to see all sorts of changes in the labor market because of transitioning from a 20% unemployment system to whatever the future holds. It makes a really big difference if you use this money to help the unemployed, versus letting companies sort of stockpile the money and do with it what they will, with the assumption they’ll do the right things.”

The largest portion of the US pandemic response will ultimately be the nearly $500 billion deployed to the Federal Reserve to provide cheap loans to rescue businesses, states and municipalities. That’s because the Fed will use it as a backstop to provide far more funding to the economy—”effectively, $1 of loss-absorption is worth $10 worth of loans,” Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell explained last month.

Ramamurti is concerned that the Federal Reserve’s lending facility for large companies, called the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF), doesn’t impose enough restrictions on recipients, whether to prevent them from laying off workers, overpaying executives, or passing the money out to their shareholders in the form of dividends or share-buybacks. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve’s facility for mid-sized companies, called the Main Street New Loan Facility, does require recipients of aid to follow some of those restrictions.

“That,” Ramamurti says, “raises the question, why are these mid-sized businesses subject to more stringent standards than the big companies?”

Neither of those Fed programs have begun lending or finalized their terms, according to an April 28 report it sent to Congress. The CARES Act requires only new loan programs to implement restrictions on compensation and capital distribution, and the PMCCF will purchase bonds at penalty interest rates because it is intended to be a second option to the public markets. Indeed, bigger companies have seen their access to capital in the markets—backstopped by the Fed’s pre-CARES actions—remain fairly robust.

The health of large firms is positive news for the economy overall, but it won’t dampen fears that smaller firms may struggle in the oncoming recession.

“To me, the key question about this whole program is whether this half a trillion dollars is going to be used fundamentally to support workers by keeping them on payroll and keeping them attached to their health insurance,” Ramamurti says. After he called for the Fed to be more transparent about lending, the central bank said it would offer monthly disclosures of the companies who receive the funding. But Ramamurti says he wants more details about the specific lending agreements.

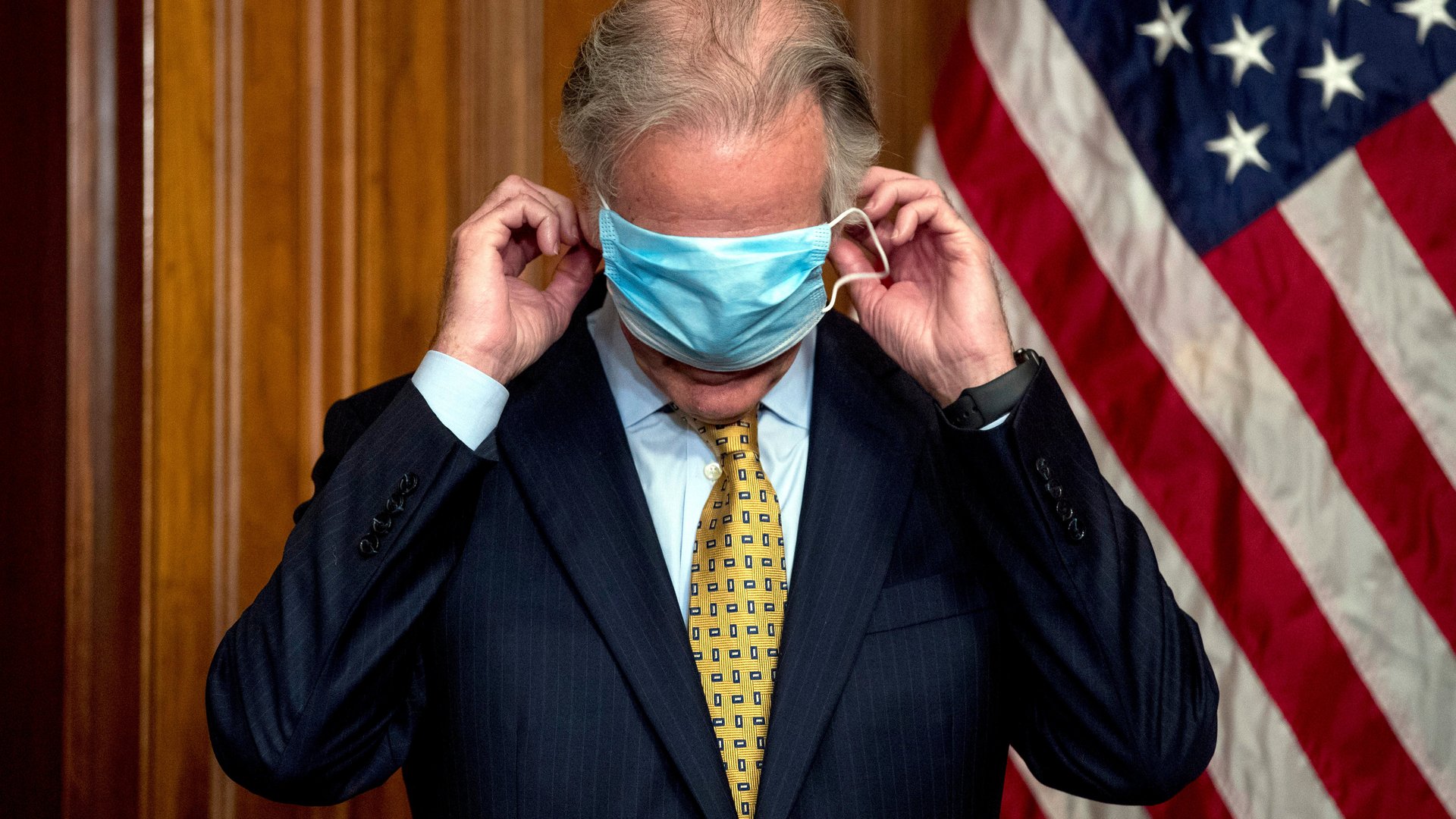

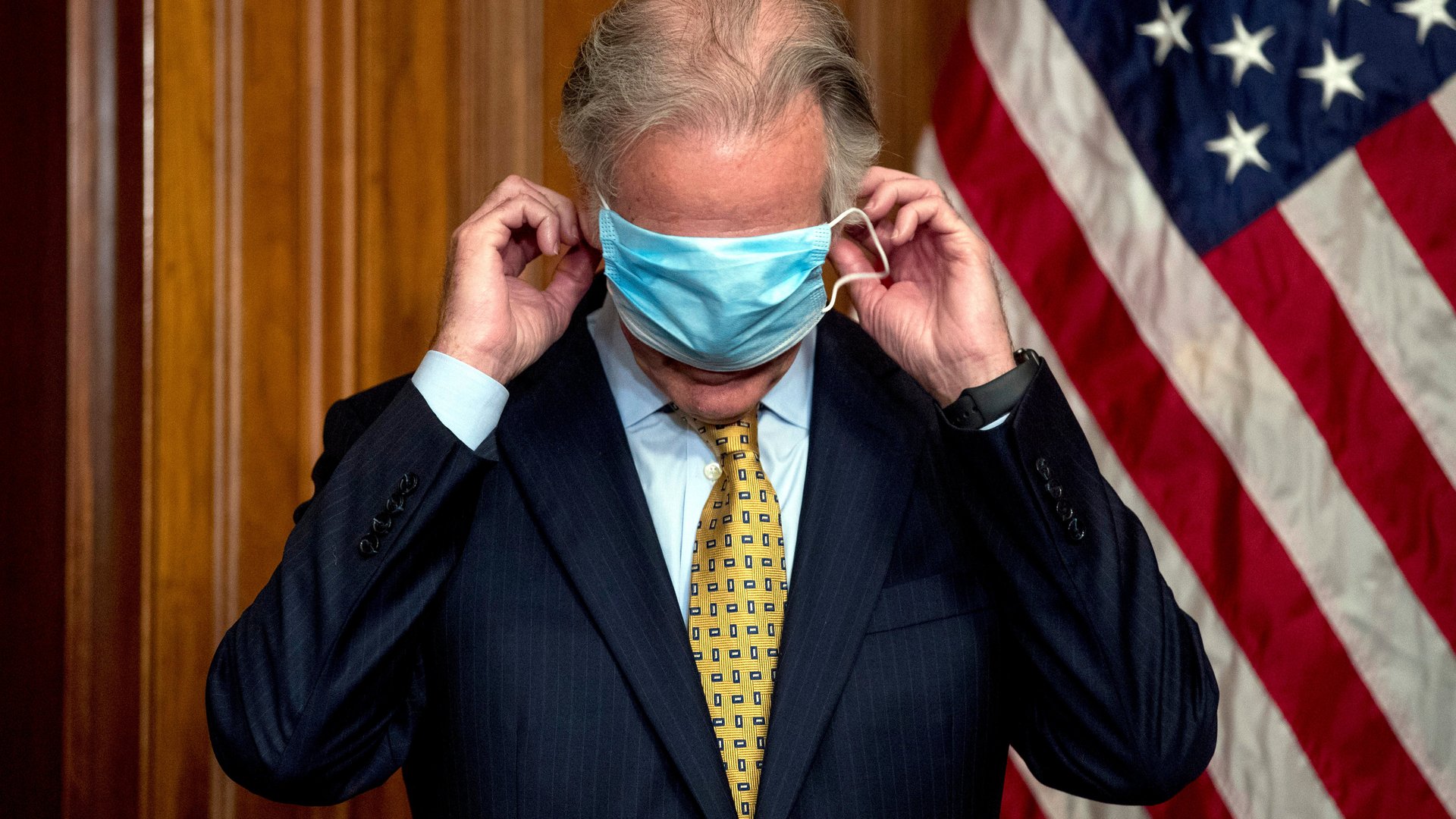

The Congressional Oversight Commission is expected to deliver its first report on the pandemic response by May 8. Yet Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell and House speaker Nancy Pelosi have yet to choose its all-important chair.