What profiles of New York City coronavirus patients say about social inequality

Back in early April, when the coronavirus pandemic was rapidly expanding in the US, some observers had the impression it would act as a kind of leveler. New York governor Andrew Cuomo called the virus “the great equalizer” because it doesn’t care who you are.

Back in early April, when the coronavirus pandemic was rapidly expanding in the US, some observers had the impression it would act as a kind of leveler. New York governor Andrew Cuomo called the virus “the great equalizer” because it doesn’t care who you are.

This was quickly revealed as wishful thinking, at best. In fact, if the virus has done anything for inequality, it has been to highlight it. Those with fewer privileges have less opportunity to practice social distancing, for starters. But the disadvantages run deeper.

A study published on April 22 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) looked at the profiles of 5,700 patients hospitalized with Covid-19 in New York City. While it’s a limited study done in one city, it offers important insights.

According to the report, nearly 65% of those admitted were insured through Medicare or Medicaid. Over 40% were Medicare patients, meaning age 65 or older and thus at high risk of serious infections, while more than 20% were covered by Medicaid, which is a proxy for low income.

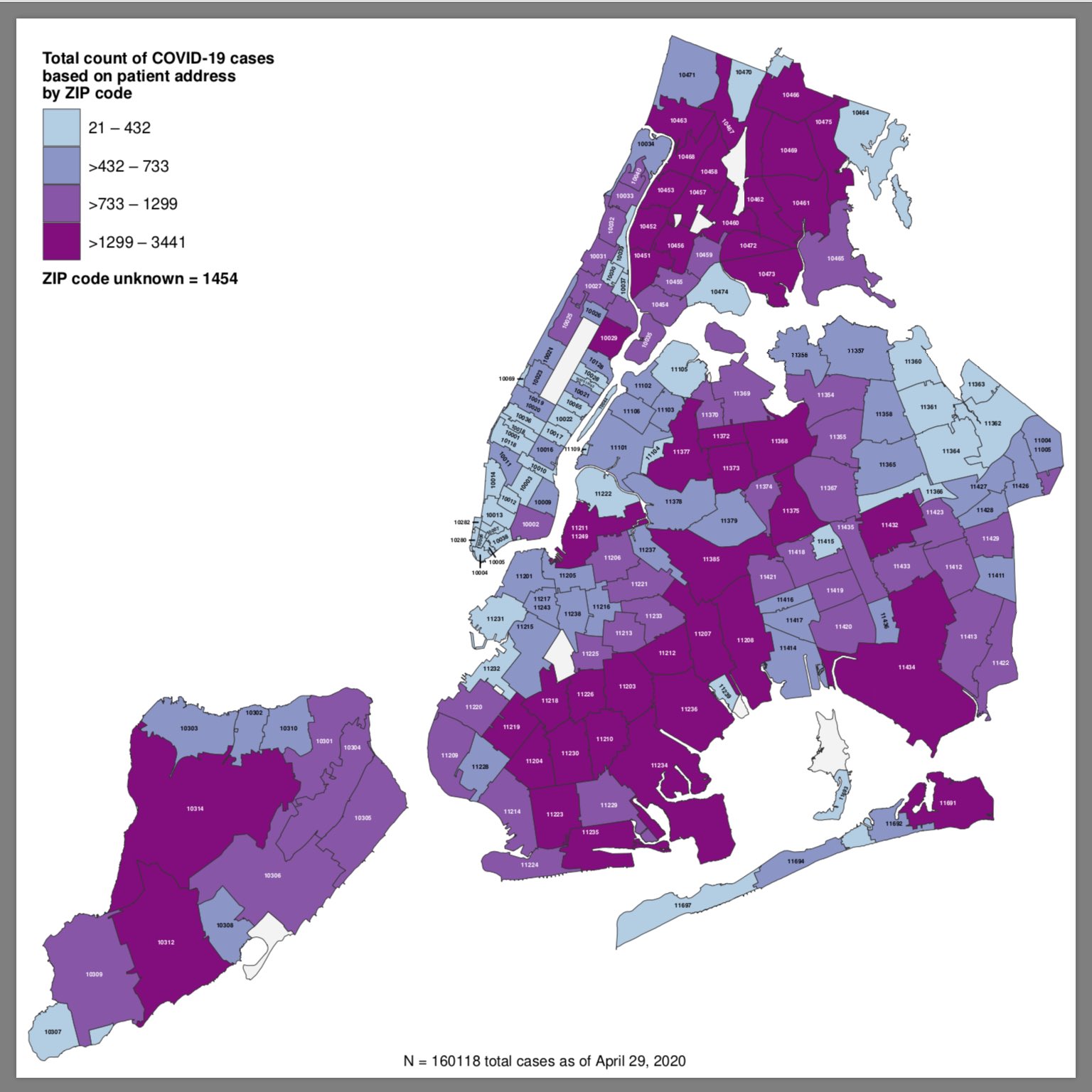

A map published by the city summarizes the picture well: The areas with the most Covid-19 cases are by and large the ones where incomes are lower and minority populations are larger, or both.

Another revealing aspect of those hospitalized: their preexisting conditions. Only about 6% had no other medical condition, and another 6% had only one, while 88% had more than one.

Safiya Richardson, one of the study authors and a professor at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research at Northwell Health, said the study is clearly limited in its scope, and doesn’t, for instance, investigate how much more likely people with specific conditions are to contract the virus or experience serious complications. “For us, this was really to give the readers a sense of what [coronavirus] patients look like, and what are the most common co-morbidities: hypertension, diabetes, obesity,” she told Quartz.

Hypertension was the most common condition among the patients, affecting 56.5%, followed by obesity (41.7%) and diabetes (33.8%). These also happen to be exactly the kind of chronic conditions that disproportionally affect people of lower income.

“It is established that health is dependent on socioeconomic factors,” said Gabriela Oates, a professor at the school of medicine of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Oates, who researches the effects of social determinants of health, said that the correlation between those factors and health is especially strong in the case of chronic disease.

Genetic makeup and predisposition, said Oates, is not the only thing that matters to whether someone may develop a chronic disease. It’s income, education level, occupation, conditions of living and other socioeconomic factors that play a disproportionate role in health, together with behavioral factors. But health behaviors, too, are essentially a function of privilege: Unfavorable ones, such as smoking or eating less fruit and vegetables than recommended, or leading a sedentary lifestyle, are very much dependent on one’s position in society.

“Although there is an element of choice, [these behaviors] are to a large extent socially determined. They require time, money, and education” Oates told Quartz. “It takes resources to be healthy.”