One US town weathered floods, a tornado, and its first Covid-19 death on the same day

Easter weekend was rough for Kevin Smith.

Easter weekend was rough for Kevin Smith.

As the mayor of Helena, Arkansas, Smith registered the seriousness of the coronavirus pandemic in early March, during a business trip to Washington, DC. On the flight home, he was disturbed by the number of people wearing masks, and decided he would do what he could to flatten the curve in his cotton-farming town of 12,000 on the Mississippi River, two hours east of Little Rock.

He issued an emergency declaration and set up a task force. He started gathering personal protective equipment for first responders and let households and businesses off the hook for some utility bills. He made the highly unpopular decision to cancel a much-anticipated student musical, for which dozens of grandparents were due to come to town.

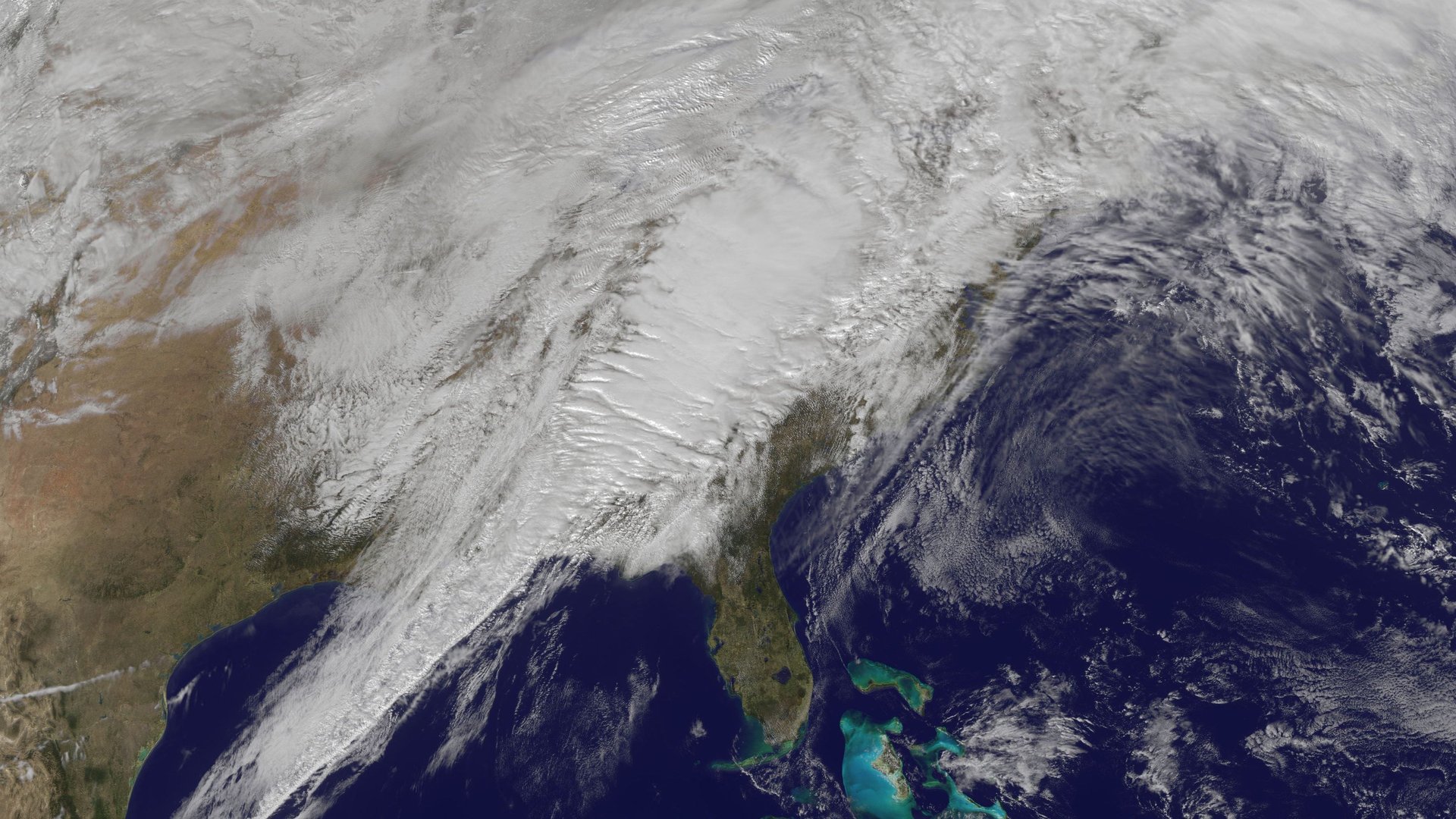

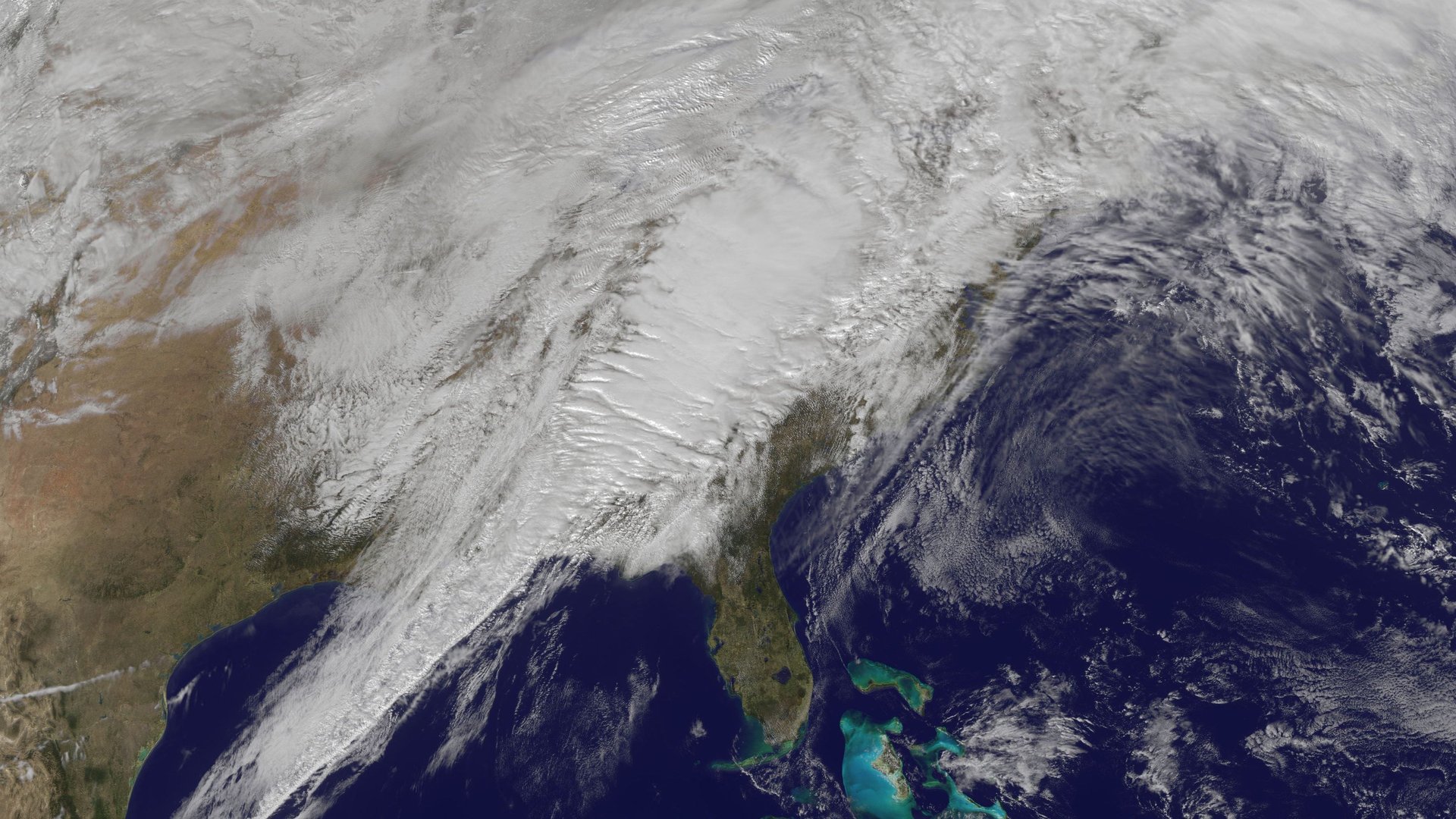

On Easter Sunday, “we didn’t go to church because of the virus, like I’ve done every Sunday in my life,” Smith said. Instead, he watched the weather report, which showed grim conditions spreading across the southeast. Severe thunderstorms began to pelt the town. A tornado touched down on the horizon. By 9 pm, the winds were high enough to rip up hundreds of trees and power lines; debris soon blocked access to the hospital. Six thousand homes lost power. The nursing home lost water. Streets began to flood, with people trapped inside.

Then Smith got a call: As if the day wasn’t hard enough already, the city has just recorded its first death from Covid-19.

“We had emergency response plans for flooding and tornadoes, old and dusty in our office,” he said. “But nobody had a plan for a pandemic. We got hit unprepared having both at the same time.”

As Covid-19 continues to shake communities around the United States, a season of extreme weather is gathering steam. NOAA predicts above-average rainfall and “widespread” flooding all along the Mississippi River this spring. Penn State researchers are warning of “one of the most active Atlantic hurricane seasons on record.” Above-average wildfire potential is projected across the Southwest and Northwest US.

Natural disasters always strain the resources of small towns like Helena. But the pandemic has erased any built-in redundancy in response plans, made some go-to responses (sheltering evacuees in schools, for example) obsolete, and exposed new vulnerabilities.

“I’m extremely worried about any disaster that happens during a pandemic,” said Samantha Montano, a professor of emergency management at the University of Nebraska-Omaha. “When people ask disaster researchers, ‘What’s the worst-case scenario,’ in terms of strain on the system, usually we say having multiple disasters happen at once. And that’s the exact scenario we’re in right now.”

On Easter Sunday night, as storms pummeled the town, Smith drove around, helping police and firefighters as best he could. The 911 dispatch office and the police station had both lost power, and neither had a working generator. Smith encountered a man whose truck had slid off the road; while trying to dislodge it, the man had become pinned underneath. In the heat of the moment, as he helped the man out, Smith realized he had left his gloves and mask in his car.

“We certainly did try hard” to practice social distancing and other health precautions, Smith said. “But in the middle of an emergency, when you need to chainsaw a tree to let an ambulance get by and it’s raining, you can’t think about if you’re breathing on someone or not.”

After the weather cleared and the flood subsided, the full scale of the disaster became more clear. Smith learned that many of his residents had heeded warnings from state officials to prepare for quarantine in April and spent most of their paychecks on groceries. With a median household income of $22,400, Helena is among the poorest communities in the country. When the storm cut off power—for more than a week, in some neighborhoods—many of those stockpiles went to waste.

“We spent weeks telling them to stay home, stock up, then they immediately lose it all,” he said. Church groups have since been instrumental in delivering food aid, he said.

A team from the American Red Cross arrived and handed out some supplies, he said, but left without setting up tents, loaning trucks, helping with paperwork, or providing other forms of assistance Smith was used to receiving after disasters.

Greta Gustafson, a spokesperson for the Red Cross, said the agency has “created new protocols to help keep everyone safe in this environment.” They’re providing services digitally whenever possible and placing evacuees in hotel rooms rather than shelters. At the same time, Montano said, the Red Cross’s emergency response teams are short-staffed, because they typically rely on volunteers, including retirees who may be at higher risk for coronavirus infection.

For cities that suffer widespread damage from disasters, social distancing and the general slowdown of construction work will likely cause cleanup and repair efforts to take longer and be more expensive; an analysis by the consultancy Risk Management Solutions projects that the cost of a major hurricane making landfall during the pandemic could be 20% higher than normal. And as the pandemic response drains local economies and municipal budgets, many cities could be forced to put on hold the very infrastructure upgrades meant to blunt the impact of climate disasters.

Emergency response and coronavirus precautions needn’t be mutually exclusive, Montano said. The key is for local leaders to not only make plans, but make sure their citizens know how things will be different from past disasters.

“Officials need to start pushing out messaging as soon as possible for what preparedness looks like, so people can take individual actions and shift their own expectations,” she said.

For now, Smith is working through a coalition of Mississippi River mayors to get more PPE and testing kits, which he said has been far more helpful than the state or federal governments. Helena has had five confirmed Covid-19 cases, but no further deaths. Smith’s next preoccupation is the local dump, which is not just an essential public service but also a vital source of municipal income. It has just five employees, and serves the hospital and neighboring counties. If one worker tests positive, all five will have to go home for two weeks. He’s received no guidance from higher authorities on how to prepare for that contingency.

“I don’t want the garbage piling up. These are questions mayors have been asking that we don’t have answers to,” Smith said. “Every day has been like a month, seems like. I used to joke: ‘What else could happen?’ My thing now is to never say that again.”