Women are struggling more with mental health under lockdown than men

It’s no surprise that people are having a hard time mentally in lockdowns resulting from the coronavirus pandemic.

It’s no surprise that people are having a hard time mentally in lockdowns resulting from the coronavirus pandemic.

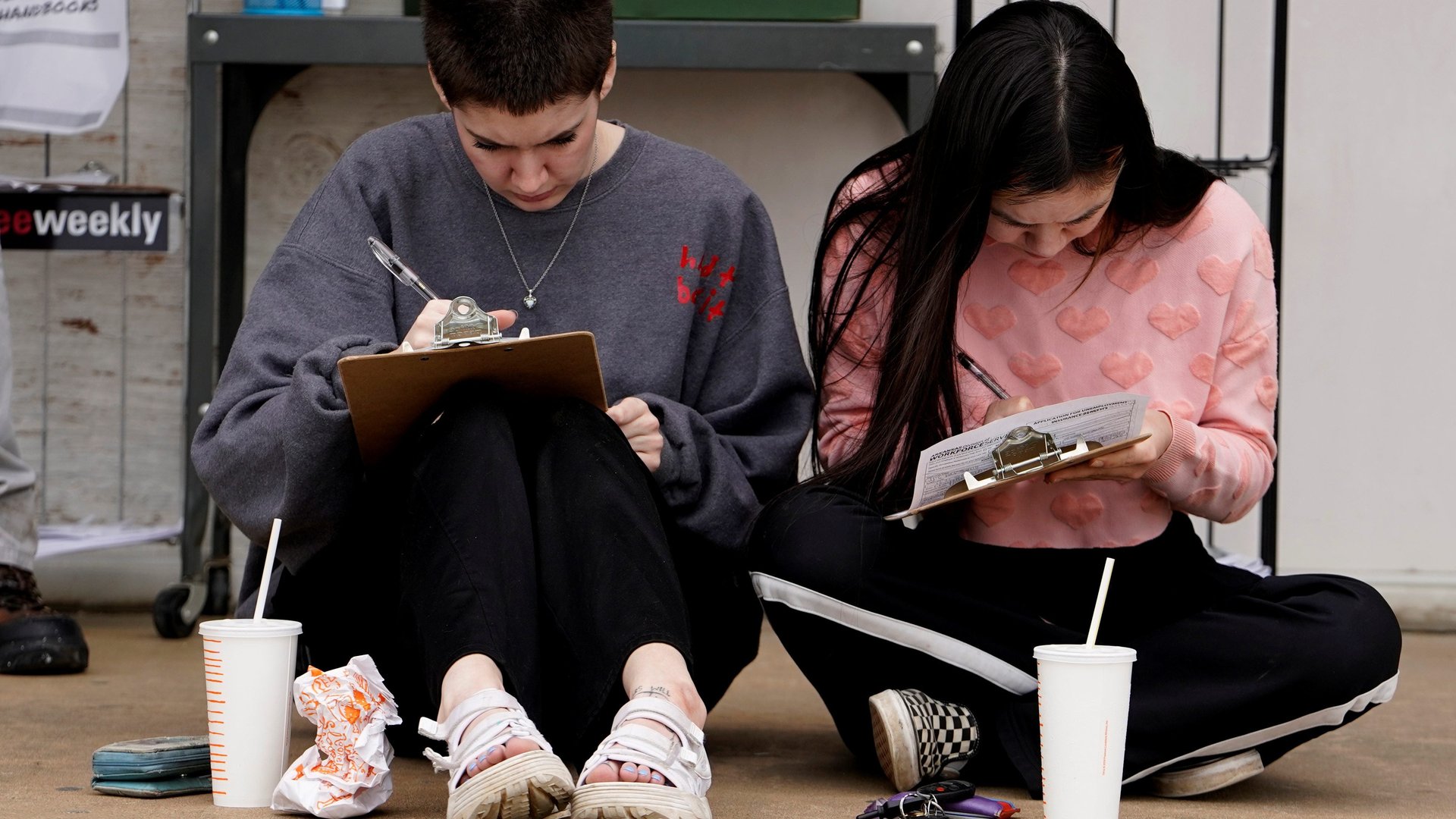

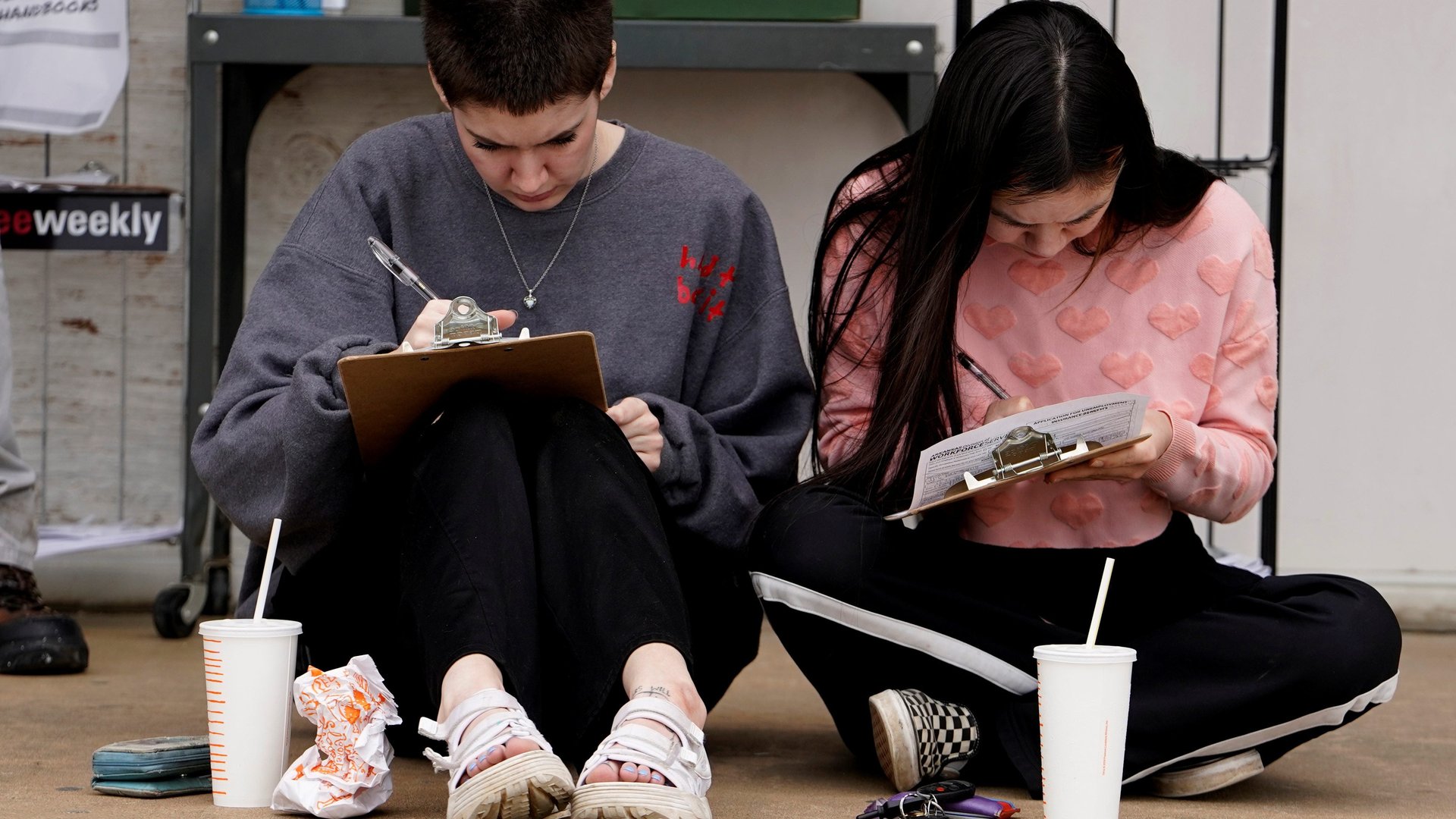

But a new study from researchers at the universities of Cambridge, Oxford, and Zurich has revealed a stark difference in the way that unhappiness is distributed. The fall in mental health in US states that entered lockdown can be explained, they found, entirely by a change for the worse in the mental health of women.

A gender gap in mental health in the US already existed pre-pandemic, but it has significantly widened. The researchers studied a total of 8,000 people across US states in two waves of questioning, in late March 2020 and mid-April 2020, during which time many states entered lockdown. To analyze respondents’ mental health, they asked people to reflect on how they had felt over the past two weeks using a set of five statements, such as, “I have felt cheerful and in good spirits.” People responded using a scale developed by the World Health Organization, which was then translated into a “score.”

The fall in mental health among male respondents was small and statistically insignificant, they discovered. There were much larger declines in how women reported feeling. Overall, the researchers found that the mental health gender gap had increased by 66% in states under lockdown.

There are plenty of reasons why women might be suffering more, both globally and in the US, during the coronavirus pandemic. With schools closed, women are taking on more childcare responsibilities, and more homeschooling, than men, the same academics also found in a study published last week. That may be leading to women working less or giving up their jobs entirely. Or, they may be feeling less satisfied by the work they are able to fit into their compressed time.

Previous research has found that women tend to do more domestic work, like cleaning, even when they also have paid employment. (The more women earn, the more domestic chores they do compared to their husbands, a previous study found.) With families stuck at home, the amount of housekeeping work like cooking and tidying increases, while outside sources of help like cleaners are also not available, or much less so, during lockdown.

Women are also losing their jobs more than men, the researchers discovered.

But what’s really surprising about the new research on mental health is that it can’t be explained by any of the factors above. The scientists controlled for whether respondents had suffered specific economic impacts, like job losses or pay cuts. They also controlled for the presence of children under 18 living at home, and for other increased care-giving responsibilities. Finally, they controlled for local deaths from Covid-19, to check whether being in a place with high mortality was a factor. None of these reasons explained the way women’s mental health fell compared to men’s.

Christopher Rauh from Trinity College Cambridge, one of the study’s authors, confirmed that losing one’s job or having extra responsibilities did correlate with a decrease in mental health: It just didn’t explain why women were suffering more than men. Single women and those who had suffered no economic harms were also affected. “We do find all the things that you’d think would matter, matter, but they can’t explain the gender gap,” Rauh said.

And there are also reasons men might be more at risk of lower mental health. Overall, more men die of the disease than women. They are also statistically more likely to be a family’s breadwinner, which could increase work-related stress.

Without more evidence, it’s impossible to know what is driving women’s mental health lower than men’s, Rauh said, and because this situation is unprecedented, there’s nothing to compare it to in order to draw a conclusion. In the wider literature, women do already exhibit more unhappiness than men, so it’s possible the pandemic has made more extreme some of the factors that already made up that difference.

In another wave of surveys the researchers—Rauh together with fellow economists Abi Adams-Prassl, Teodora Boneva, and Marta Golin—plan to dig deeper into work-related factors. For example, while women may have often been working more “flexibly” than men before the pandemic struck, that flexibility might have been dictated not by their specific needs, but by their employers.

It’s also possible there are factors at play which are impossible to capture in a study with this design, Rauh explained. Anecdotally, many women have described giving up their own work in favor of their male partners because of a need to protect often higher-paying male careers during an economic downturn. Exploring any such a link would necessitate surveying more than one member of each household, Rauh explained. Domestic violence has increased during lockdowns in many places, but wasn’t captured in this study.

Is it possible that men didn’t notice, and therefore didn’t report, their falling mental health? Other literature has certainly pointed to the idea that women may be quicker to identify feelings of sadness. Either way, it will take more research to discover why lockdown is having such a disproportionate effect on women’s happiness.