Emerging markets have $318 bln more in offshore debt than we thought they did

Developed economies looked on in horror the last time we had a giant emerging-market meltdown, in the late 1990s. But they were pretty insulated from the impact.

Developed economies looked on in horror the last time we had a giant emerging-market meltdown, in the late 1990s. But they were pretty insulated from the impact.

How times have changed. Not only do rich-country corporations rely much more heavily on consumers in emerging markets; recent research says those markets may also be a lot more vulnerable to big swings in currency value and capital flow than most of them realize.

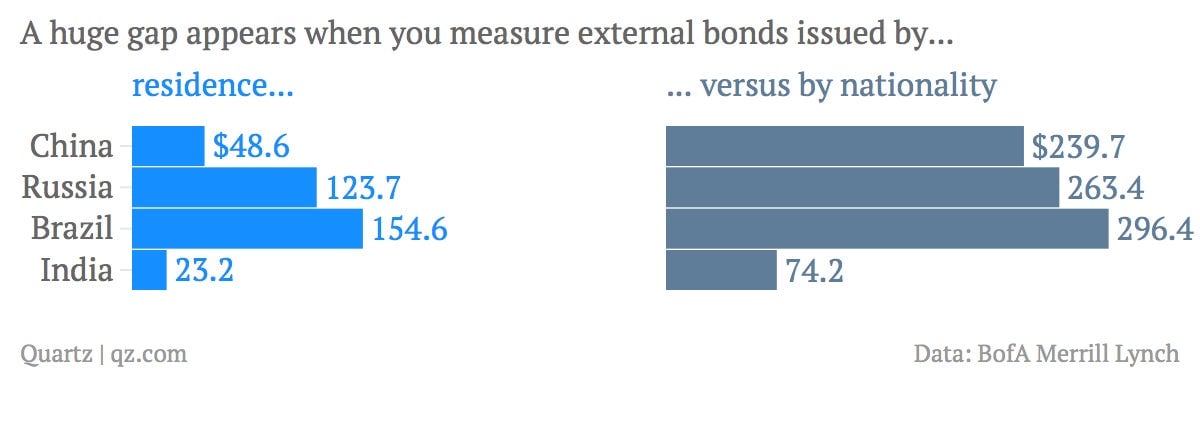

That second point is the big one. There’s a nasty surprise lurking in the amount of external debt issued by emerging-market banks and companies. Balance-of-payments data measures this debt on the basis of the issuer’s residence, not nationality. Debt issued offshore doesn’t show up in the data based on residence. And that offshore debt has been growing.

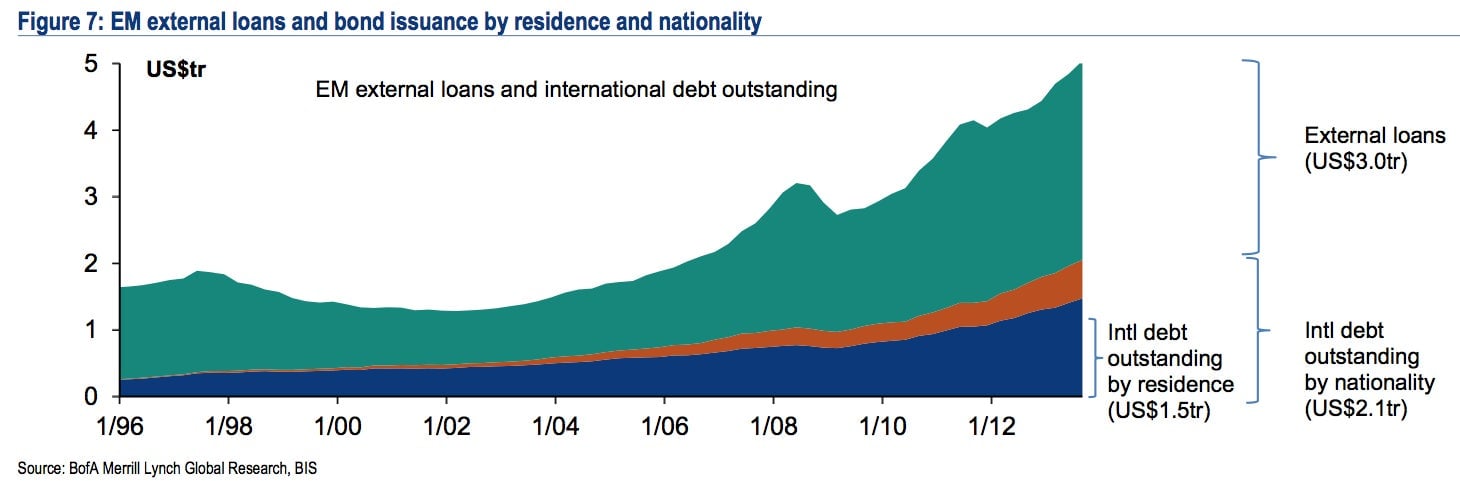

Since the last crisis, emerging market banks and companies have been borrowing offshore like crazy; they’ve raised $1 trillion in externally issued bonds since the third quarter of 2008, according to Bank of America/Merrill Lynch (BofA/ML). That’s $318 billion more than you’d get calculating by residence alone.

How did this happen? Well, many more overseas affiliates of emerging-market companies now have access to foreign bond markets than did in 1997. After 2008, when the US Federal Reserve began its first program of quantitative easing (QE)—depressing US interest rates in an attempt to juice the economy—these companies were able to borrow in “hard currencies” like the US dollar or euro at rates much lower than those they could get back home.

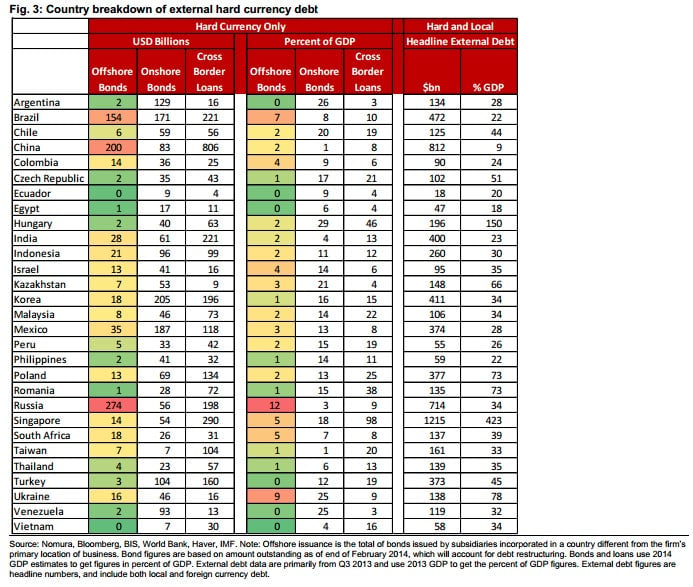

BofA/ML flags the BRIC countries as having some of the more worrisome of these “hard currency” debt problems. As FT Alphaville highlights (registration required), Nomura sees danger in the offshore debt-to-GDP ratios of Russia, Brazil and Ukraine.

The scary thing now is that, as the Fed “tapers” (winds down QE), money fleeing emerging markets will drive down the value of local currencies and leave borrowers struggling to stay afloat. Say a Russian company issues debt in dollars; if the ruble loses value against the dollar, the company will end up owing more than it borrowed, in ruble terms.

Then there’s the question of what all this is invested in. Some went into overseas assets like mines or oilfields. Those are fairly insulated from big currency fluctuations. But a decent chunk is likely in more volatile stuff like emerging-market stocks and property. As the Fed tapers, sucking dollars out back out of emerging markets, the value of those assets could plummet. And those assets are the underlying collateral of debt owed to overseas bond investors.

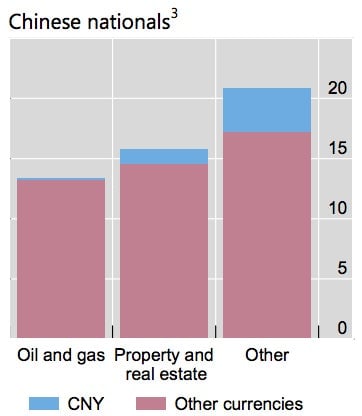

For instance, BofA/ML worries that China’s enormous trust loan sector, a crucial off-balance-sheet lending channel, is partly funded by overseas debt issuances. And a recent Bank of International Settlements paper (pdf, p.23) found that China’s property firms have taken out more foreign-currency loans than its oil and gas companies have, even though the oil and gas sector has much more reason to be shopping for offshore investments.

If the taper does prompt emerging-market assets to drop in value, those countries will need more money flowing into their financial systems. They could do this by, for example, upping trade surpluses (exporting more/importing less), privatizing, opening up equity markets to more foreign investment—or simply by having their central banks kick up their lending. The only worry is, that might encourage their companies to rack up even more debt.