The US is in for a brutal—and expensive—hurricane season

A potent combination of ocean conditions brewing in both the Pacific and Atlantic have climate scientists worried that 2020 could be one of the most active hurricane seasons on record. And with recovery and rebuilding resources stretched thin by the coronavirus pandemic, the economic toll of those storms that make landfall could be more painful than usual.

A potent combination of ocean conditions brewing in both the Pacific and Atlantic have climate scientists worried that 2020 could be one of the most active hurricane seasons on record. And with recovery and rebuilding resources stretched thin by the coronavirus pandemic, the economic toll of those storms that make landfall could be more painful than usual.

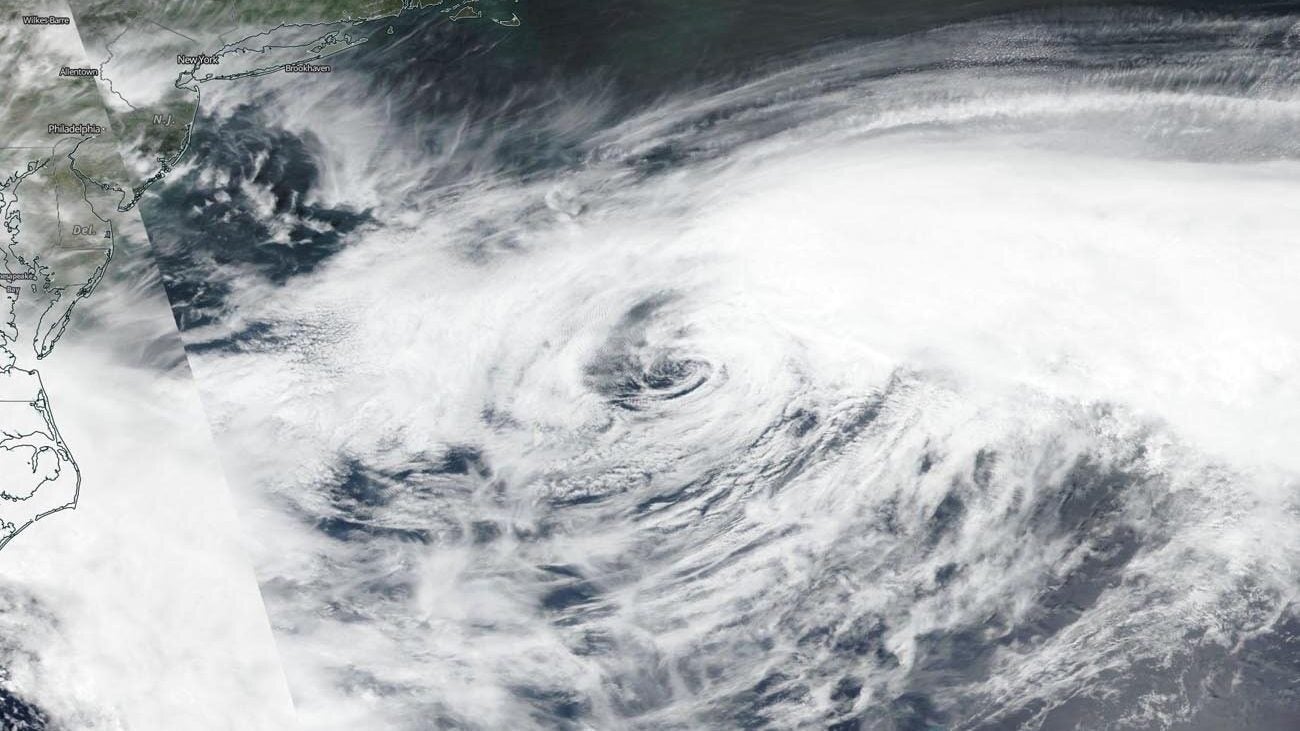

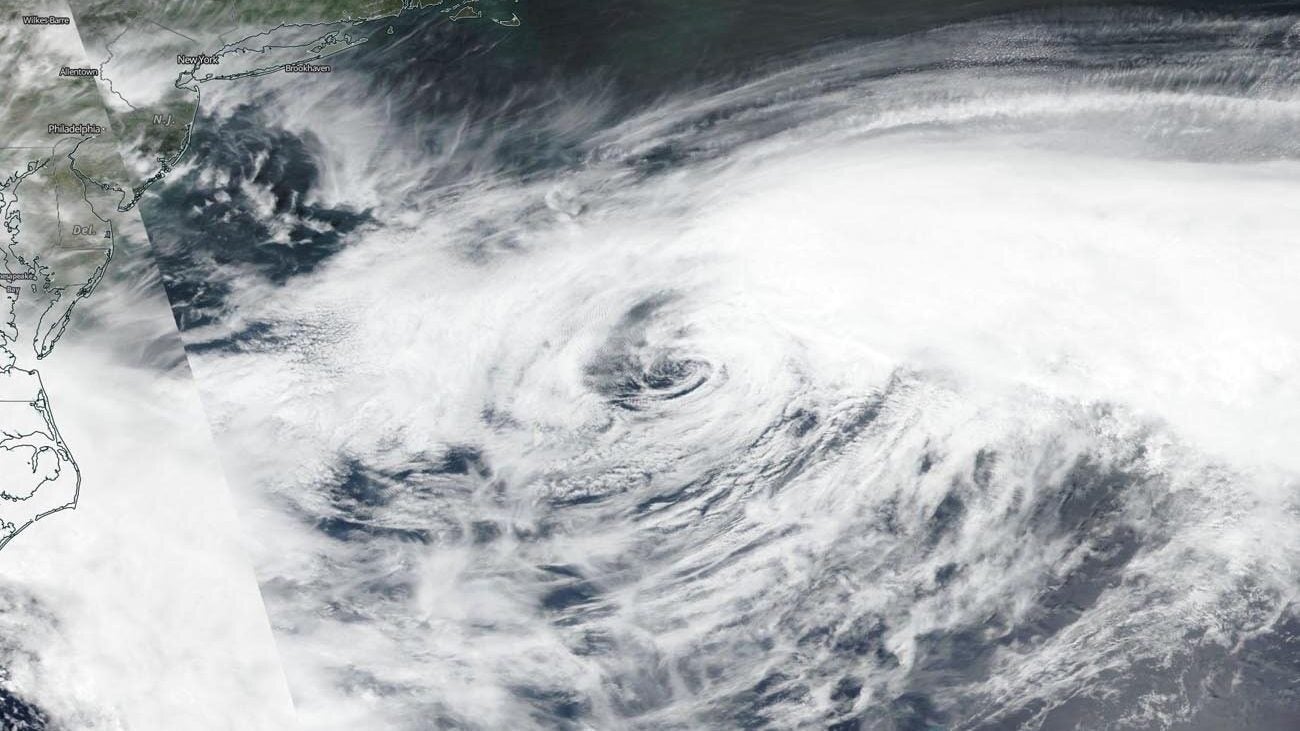

In a seasonal forecast released today, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration projected a 60% chance of an above-average Atlantic hurricane season. The agency is anticipating up to 19 storms big enough to merit a name, of which up to 10 may grow into hurricanes. (The average since the 1980s has been 13 such storms, about half growing into hurricanes.)

The bulk of those storms are likely to form between August and October. It’s too soon to know how many will make landfall, says Suzana Camargo, a climate scientist at Columbia University, because the atmospheric conditions that influence their paths are much less predictable than the ocean conditions that make them form.

But for those that do cause damage, the recovery and rebuilding process will likely be much more complicated and expensive due to the pandemic. An analysis by Risk Management Consultants projected that rebuilding costs for a major hurricane could be up to 20% higher than normal as a result of coronavirus-related supply chain bottlenecks and labor shortages.

With so many building projects delayed, buildings damaged in a storm will likely be left exposed to the elements—and vulnerable to further decay—for longer. Many post-disaster construction workers who normally travel to disaster zones from neighboring cities or states in search of work are staying closer to home, according to Daniel Castellanos, a New Orleans-based labor advocate who helps organize such workers for the group Resilience Force. For the same reason, skilled tradespeople like electricians and plumbers, who are always overworked after disasters, will be in even shorter supply.

Already, hurricane-related damages in the US cost around $54 billion per year, according to federal estimates.

Jeffrey Schlegelmilch, deputy director of Columbia’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness, said the pandemic will also cause a bottleneck for federal relief funds. Once post-disaster aid has been appropriated by Congress, it flows through a tangle of dozens of federal offices, and can take months or years to reach those in need. After Hurricane Sandy, victims weren’t even able to start an application for funds until at least six months after the storm, he said.

In the midst of a recession, federal funding becomes even more important, since households have less to spend on their own home repairs. But since the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which leads the response to hurricanes, currently has its hands full with Covid-19, the disbursement process will likely be even slower.

“There are so many bureaucratic layers before that money actually gets into the hands of a builder to start fixing your home,” Schlegelmilch said. “These systems are really being stretched to their limits.”

On Wednesday, the hurricane season presented its first extreme test. Cyclone Amphan slammed into India and Bangladesh, registering as the killing at least 80 people and forcing at least 2 million into shelters. At its peak, it was the most powerful cyclone ever recorded in the Bay of Bengal.

Walter Mwasaa, acting Bangladesh country director for the humanitarian agency CARE International, said that in the immediate aftermath of Amphan, the government made some accommodations for social distancing by converting schools and other buildings into shelters, to spread the displaced across more locations. But the pandemic is going to severely disrupt the pathway to post-disaster economic recovery, he said: Normally, when a cyclone damages farmland and leaves rural people in need of cash, they can travel to Dhaka or other urban centers for factory or construction work. Now, even those jobs are scarce.

“With the lockdown, people aren’t moving as much, and there aren’t opportunities,” he said. “So it compounds a complex situation.”

Conversely, Schlegelmilch said, one reason for optimism could be that post-disaster funding, when it does finally arrive, can help sustain cities through economic downturns. New Orleans, for example, was less affected by the 2009 recession than the country at large because it was still being propped up with post-Katrina funding. If there’s any silver lining to having a severe hurricane season in the middle of a global pandemic, that might be it.