The legacy of Larry Kramer’s AIDS activism is in the US’s response to coronavirus

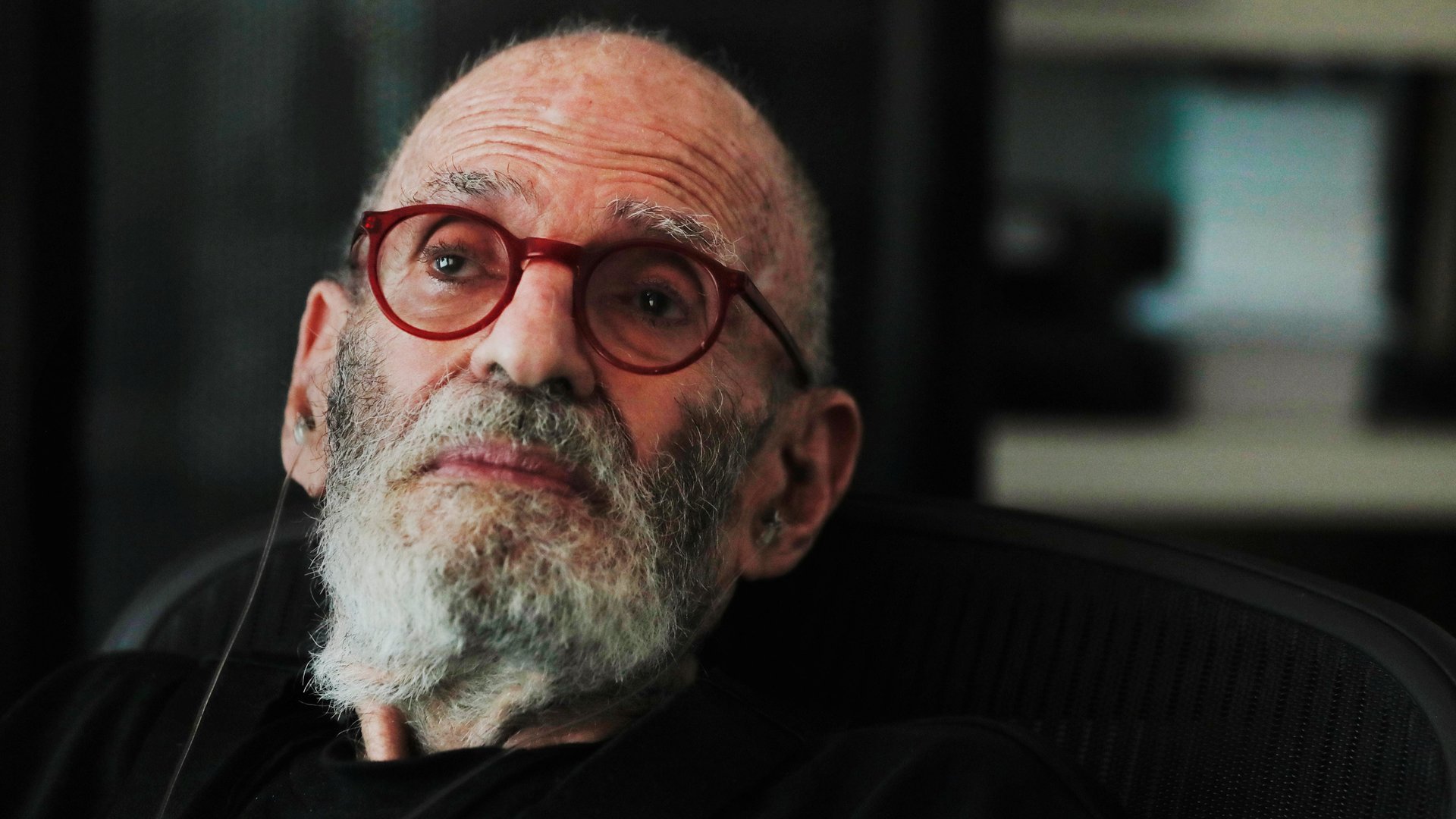

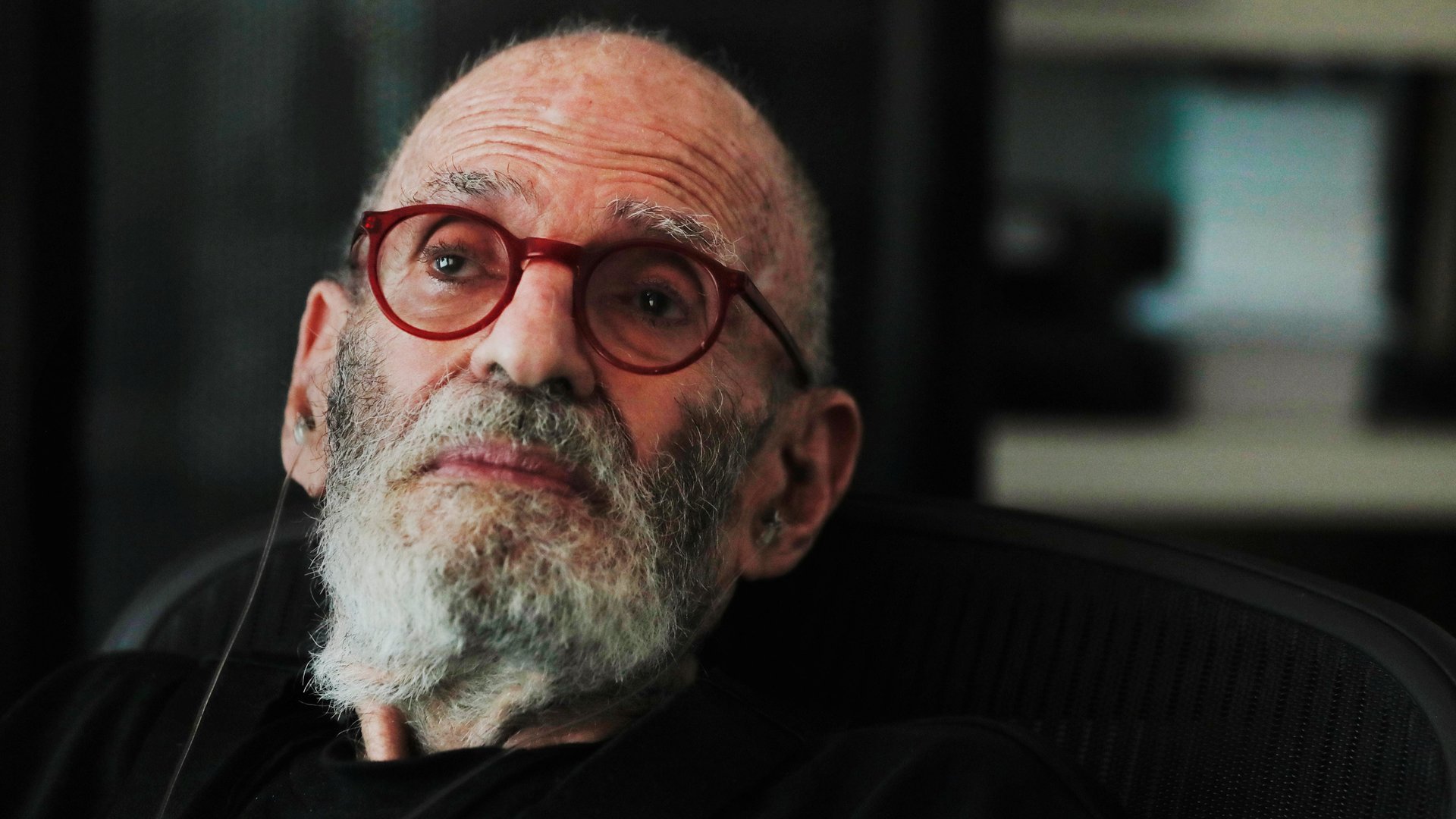

Larry Kramer, America’s most prominent AIDS activist, died yesterday of pneumonia.

Larry Kramer, America’s most prominent AIDS activist, died yesterday of pneumonia.

There is symbolism in the timing. Kramer was indispensable in his calling out the American government’s inaction as HIV spread through the US (and the world), in demanding research for a treatment, and then making those treatments available. It seems somewhat ironic that he died in the middle of another plague, as he labeled both AIDS and Covid-19.

Kramer, a playwright and author, was a founder of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), and had an unforgiving approach to activism and campaigning. He accused officials of murder and genocide because of their delay in declaring a health emergency, often calling out—as the face of the government response to that epidemic—the very Anthony Fauci who is the face of today’s epidemic.

His work—and the broader impact of AIDS activism—couldn’t be more relevant. It established the blueprint of how to hold the government accountable in the face of a health crisis.

“Larry Kramer had a vital, important role in the history of this country addressing public health crises,” Rick Berke, the co-founder and executive editor of health publication STAT, told Quartz. “He was a singular figure in that he was able to get your attention whether you liked him or not.” Berke, who covered the AIDS crisis for the New York Times, was himself a target of Kramer’s relentless campaigning.

With his coalition, Kramer staged protests, and raised his voice, called out individuals responsible, and was able to direct the press and the government’s attention to the crisis. As Fauci—a nemesis who later became a friend of Kramer’s—shows in his heartfelt remembrance, he had enormous impact in pushing the government to move faster and better and to get rid of unnecessary bureaucracy.

The coronavirus crisis is very different from AIDS. It took years to understand AIDS was caused by a virus, and wasn’t a type of cancer, and in its first decades, the epidemic was predominantly limited to pockets of society (gay, drug users, sex workers, prisoners) that were regarded by the government as somewhat dispensable. Activists were fighting for AIDS to be even acknowledged, while Covid-19 has frozen the world in a matter of weeks.

Yet at the same time, there are elements in common. With AIDS, the deadly delay of the government was measured in years—Ronald Reagan took seven years to say the word AIDS; with Covid-19, the delay was only a matter weeks (but even those weeks mattered immensely). Both diseases became very political: In the case of AIDS, it was because of the refusal to acknowledge its existence and impact; for Coronavirus, it’s the prioritizing of healthcare over business, and the administration’s unwillingness to listen to its own scientific advisors.

The legacy of AIDS activism is a level of transparency and accountability in the government’s response to Covid-19 that would have been unconceivable in the 1980s and 1990s. That was when Americans became familiar with a medical vocabulary—treatment, testing, prevention, medication cocktails—previously unknown, and when the idea that the public deserves to be educated and informed originated, Berke said.

Then there is the question of speed. “The whole way Tony Fauci and his institute operate was made faster and more efficient because of what they endured during the AIDS crisis,” Berke said. The speed of research, testing, and reporting is a direct effect of the work Kramer and other activists put in, forcing the government to let go of unnecessary red tape, and holding them accountable.

AIDS was a watershed moment in American health, and is a remarkable testament to its impact that so many of the people involved in the coronavirus critics—both in government, and those holding the government accountable—are the same. A generation of public health leaders was forged by AIDS, and they are the one’s best equipped to tackle coronavirus.

Right before he died, Kramer was working on a play on the coronavirus epidemic, and it likely wouldn’t spare criticism of Fauci, who again is the face of government response. Other important AIDS activists have since become prominent health experts—like Gregg Gonsalves, or Mark Harrington, who are now some of the country’s foremost epidemiologists—and continue to contribute to the awareness and education on the disease. They call out government’s inaction, too, openly criticizing the White House’s scientific advisors for not standing up to Donald Trump’s misleading statements, again holding the government responsible for the thousands of deaths occurring in America.

It’s hard to think of someone who could be the Kramer of this crisis, though the role of health activism is as essential as ever. That is partly because his charisma is irreplaceable, says Berke, but also because the coronavirus crisis is more complex, and divided in many intersecting issues.

For that, Berke suggests, we may not need a Kramer—but, perhaps, several. “It would be great to have an activist who could really pressure companies to move faster on treatment,” he said. At the same time, other activists are needed to tackle the myriad of other issues presented by the virus, including cost of healthcare, and the necessity of economic interventions to save jobs and homes.