China’s health scores for citizens won’t go away when coronavirus does

A government app that used digital bar codes to control citizen movements at the peak of the coronavirus outbreak in China is likely to become a fixture in people’s daily lives.

A government app that used digital bar codes to control citizen movements at the peak of the coronavirus outbreak in China is likely to become a fixture in people’s daily lives.

Hangzhou, a southern Chinese city home to tech giants like Alibaba, said on Saturday (May 23, link in Chinese) that it plans to “normalize” the use of the app, which was rolled out in February, and turn it into a “‘firewall’ to enhance people’s health and immunity” after the pandemic recedes.

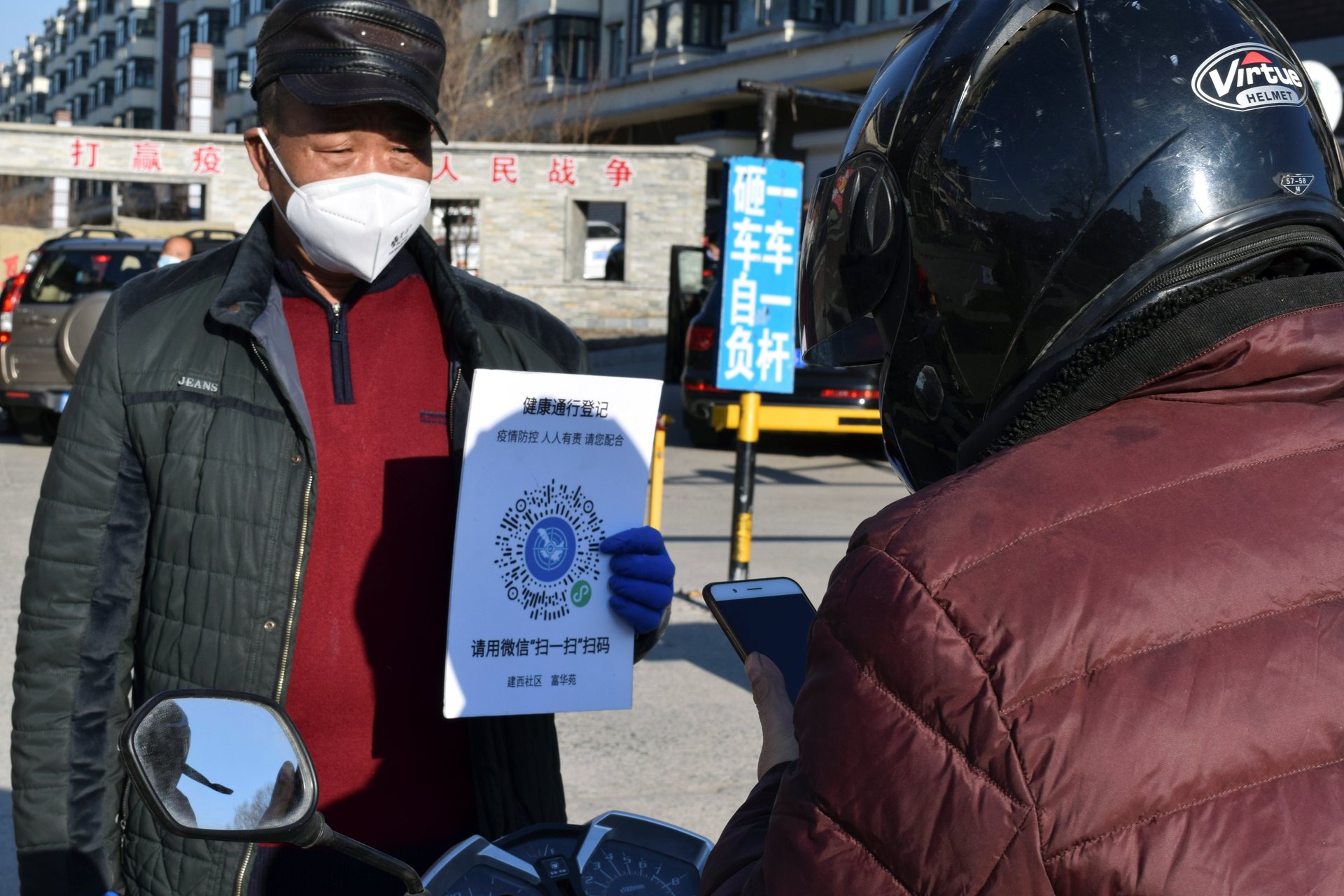

Developed with the help of Alibaba affiliate Ant Financial and social media giant Tencent, and soon made mandatory, the feature was added to Alipay, Ant’s digital payment wallet, as well as Tencent’s messaging app WeChat. It assigned people one of three codes—red, yellow, and green—based on travel history and other information, such as their own test status and contact with any confirmed cases of Covid-19, that users submit.

Local authorities would then cross examine (link in Chinese) the information with financial and transport data collected by various departments, such as users’ past bank card transactions and public transport they had used. A person assigned a green code could leave their home to ride on subways, access public buildings, and go to work when it resumed in February, while those with yellow or red codes had to self-quarantine for various periods of time.

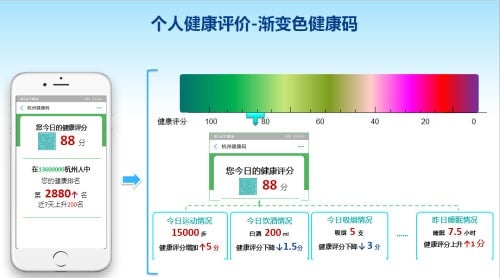

More than 1 billion people in China are covered by the system’s codes, which have been scanned over 9 billion times (link in Chinese) at various sites since February, according to Tencent.

The codes have also been crucial to China’s reopening, allowing low-risk or “green” individuals to begin resuming more normal lives after lockdowns that began in late January. While use of the codes faded in several cities, including Hangzhou, as new cases diminished, more vigorous use of the codes has returned amid concerns about a second wave of Covid-19 cases.

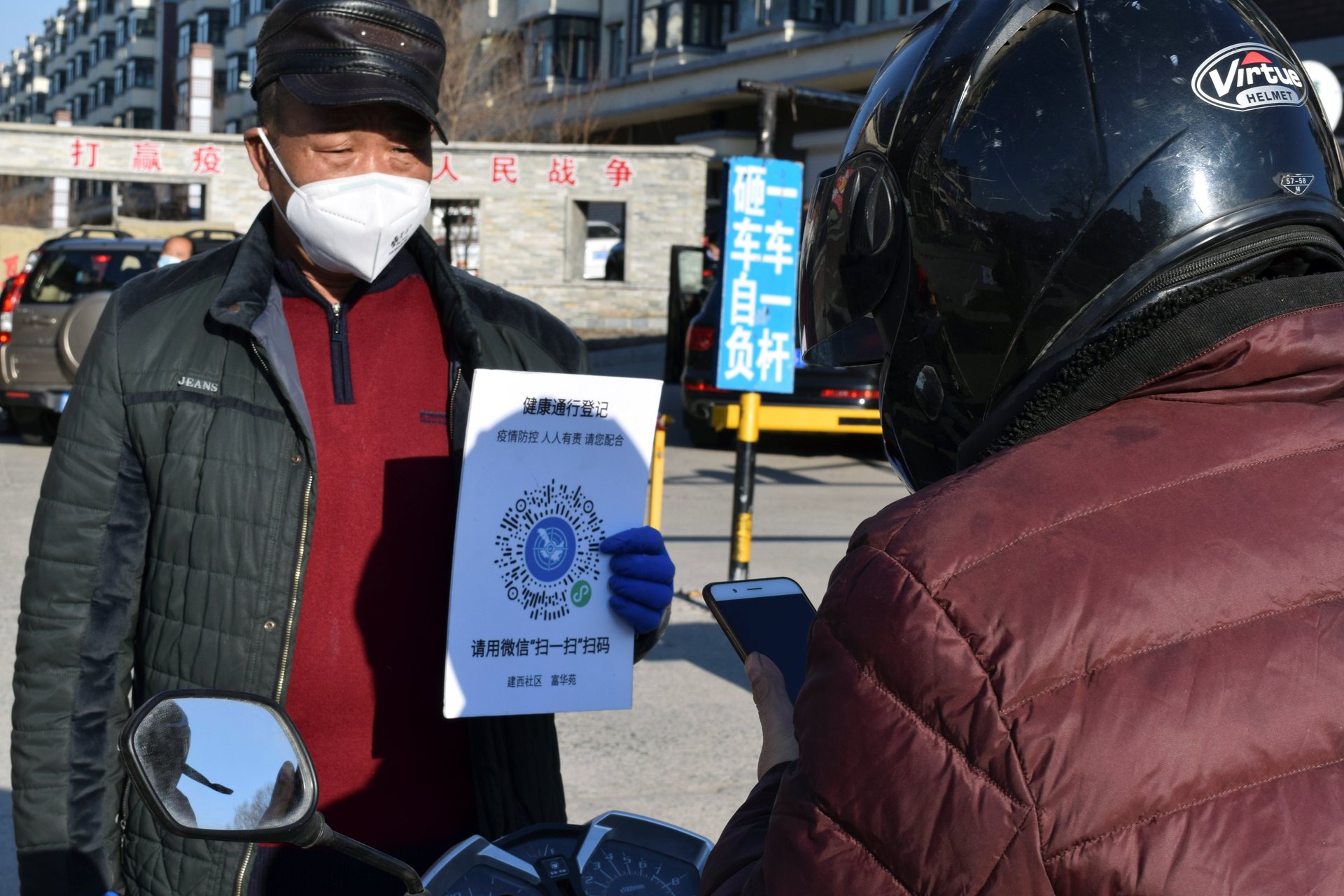

In the future, Hangzhou’s health commission said it could use the codes to assign a health status based on people’s digital medical records, including the results of health check-ups and lifestyle habits, such as how many cigarettes they smoke, steps they walk, or hours they sleep daily. It will also use more colors, ranging from green to deep purple.

Compared with Europe or the United States (paywall), Asia has been much quicker to use big data in its virus efforts. Singapore, for example, asked all of its citizens to download its BlueTooth tracing app in March, while South Korea has successfully used the timeline feature (pdf) of Google Maps to have citizens voluntarily record their locations (it also used financial and telecom data in its efforts). Taiwan meanwhile used telecom data to make sure people didn’t break home quarantines.

The use of technology in these ways has raised concerns (paywall) about privacy and “mission creep” after the pandemic—but no country has gone as far as China, where widespread surveillance already exists, and where many expected the government to use the pandemic to deepen its monitoring.

“Hangzhou health code is getting extremely black mirror-esque…” tweeted Chenchen Zhang, an assistant professor of politics and international relations at Queen’s University Belfast. “…It’s not known yet what this ‘score’ can do. Just the latest [example] of governing by quantifying everything in China.”

Even in its original form, many in China were concerned by the app, which, according to a New York Times analysis of is code, appears to share information such as a user’s location, city and an identifying code number with police. An Alipay representative told Quartz that protecting the privacy of users is a strict requirement for all third-party developers, which includes health code systems, on its platform. Earlier, an Alipay representative also said that the company had provided technical help to the developer of the health code system, and is one of the many platforms for users to access it, but isn’t involved in its rules and operations.

Compared with the existing version, Hangzhou’s vision would grant the authorities access to much more personal data. The city’s health commission did not explain how the future version of health code could obtain such data, or whether it needs to get users’ consent before doing so.

An Alipay representative said the company had not been contacted in connection with this project.

“It is extremely hard to confine government powers within an institutional cage once the powers have been let out. Now, from the top leaders to grassroots officials, all of them might be able to check citizen’s travel history one day,” wrote a user (link in Chinese) commenting on a report on Hangzhou’s plans of Chinese social media Weibo. “By then, as long as you don’t have a green code, you won’t be able to go anywhere in this country.”

Update, May 26: The story was updated with a statement from Ant Financial.