Design critic Ralph Caplan saw the 1960s lunch counter sit-in as the era’s greatest design

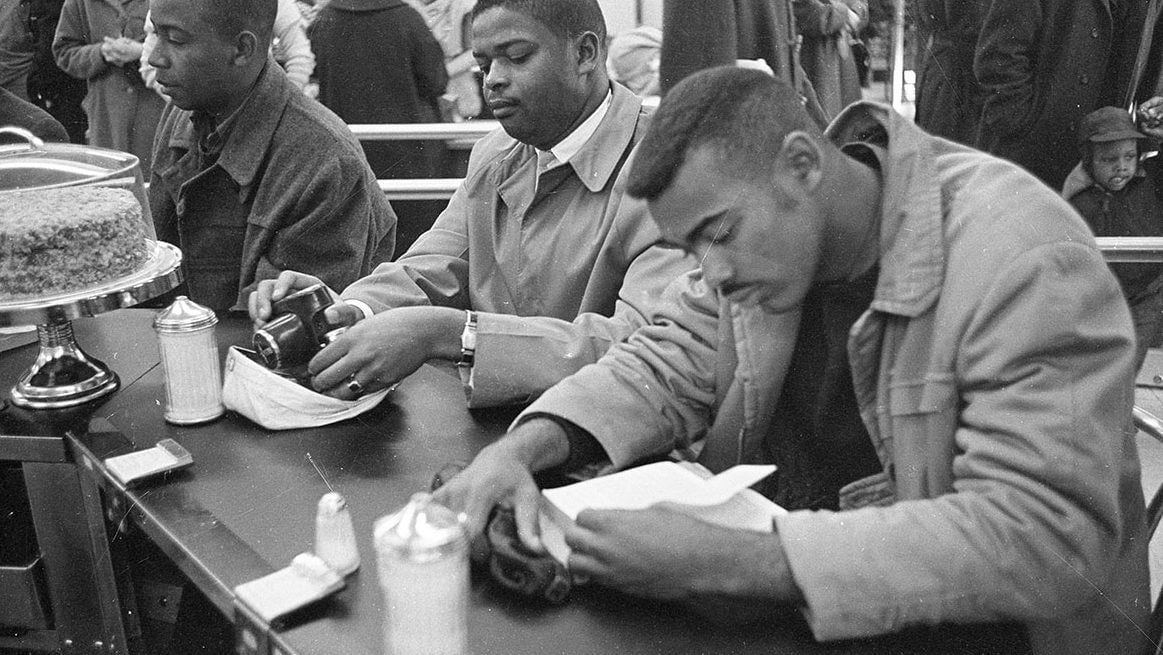

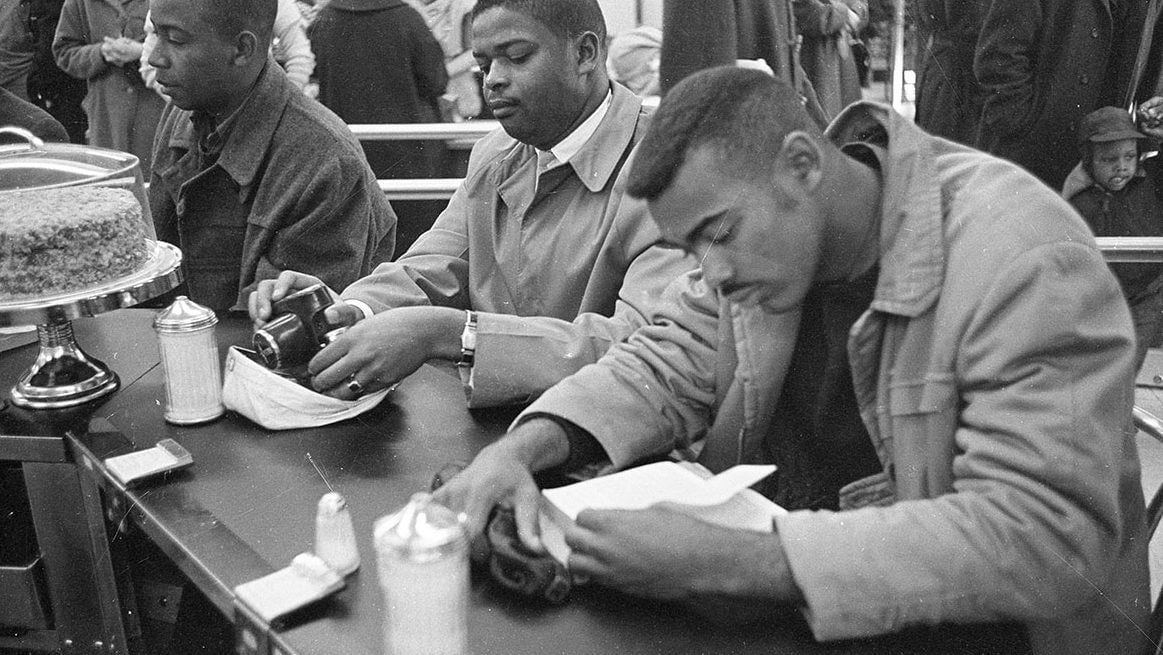

In 1964, writer Ralph Caplan joined a panel of design industry bigwigs at the International Design Conference in Aspen for a lofty-sounding thought experiment: list the best expressions of design of the era. Caplan eschewed obvious picks like the sleek modern chairs or fashion trends that today serve as visual cues of the time. Instead, he chose the “sit-in,” a form of nonviolent protest at segregated lunch counters and theaters in the American south, as his pick.

In 1964, writer Ralph Caplan joined a panel of design industry bigwigs at the International Design Conference in Aspen for a lofty-sounding thought experiment: list the best expressions of design of the era. Caplan eschewed obvious picks like the sleek modern chairs or fashion trends that today serve as visual cues of the time. Instead, he chose the “sit-in,” a form of nonviolent protest at segregated lunch counters and theaters in the American south, as his pick.

Caplan considered the sit-in a high example of “situation design,” which is akin to a specialization widely known today as user experience (UX) design. Using field research, psychology, and prototyping tools, UX designers create interventions to change the behavior of people, typically, (but not always) with the goal of improving their interactions with a service.

To Caplan, the simple act of sitting in sections reserved for white customers achieved the ultimate goal of design: It changed an unjust system. The timing and choreography of the peaceful protests orchestrated by African-American college students somehow forced businesses to radically reconsider their racist policies.

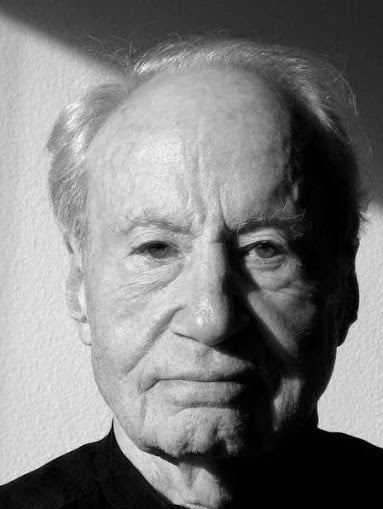

“The designer’s mission is to make things right,” Caplan said in an interview in 2010, shortly after being bestowed the Design Mind award by the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum. “There’s a difference between making things right and making things nice.”

Caplan, who passed away peacefully in New York City on June 4 at age 95, always saw a bigger horizon for designed products and a greater purpose for its creators. Long before “design thinking” became calcified in the corporate jargon, Caplan was writing about human-centered design, the perils of branding, and the virtues of reusable packaging—his first beat as a staff writer for I.D. (Industrial Design) magazine in 1957.

Born in Ambridge, Pennsylvania, Caplan didn’t study to be a designer. His early interests included poetry, theater, boxing and comedy—a sensibility that shines through his in his writing and lectures. Caplan’s first design lesson came via the civil rights organizer Bayard Rustin. “He had us play different roles—integrating a theater, integrating a restaurant and I played the role of a Black man going into a restaurant,” Caplan said in an interview for the podcast Design Matters. He said Rustin criticized his performance, explaining that a Black man would never saunter into a restaurant in such a cavalier manner. For one, they would likely walk by first to case the joint and see how friendly it was. “The whole thing was so well thought out and planned and I thought that’s what design ought to be,” he said.

In Caplan’s words

As a non-designer, Caplan had an ability to explain design to a wide audience minus the quixotic jargon of the trade. With wit and unembellished prose, he unraveled the supply chain of invention and commercial forces behind everyday objects.

For instance, he aptly described the agony of sharing cramped elevators and subway trains: “Much of modern anxiety stems from the time we spend in unnatural proximity to strangers without the preliminary sniffing that is instinctive in animals, including us.”

Or on the design of fast food meals: “What is a McDonald’s hamburger but an industrial designed product—the result of market research, facilities planning, productivity incentives, demographic studies and product engineering.”

Caplan wrote critically about faulty design, using anecdotes that taught readers how to scrutinize products, systems, and buildings in their own environment. “Ralph suffered no fools and took no prisoners, but he did it with great elegance,” says Ayse Birsel, an industrial designer whom Caplan mentored. “He changed design without designing himself…Ralph made design better by being its most caring and yet no-nonsense critic.”

“He was this living piece of design history,” adds former student Amelie Klein (nee Znidaric). “He beamed directly to us from the most exciting period in design history. He was one of the earliest real design critics in history, starting at a time when critique within the field was very un-welcome.” Klein, now a curator at the Vitra Design Museum, recalls Caplan’s humility and generosity. “He raised not only one but several generations of design thinkers and critics. We all owe so much to him,” she says.

Indeed, after he retired, Caplan was a constant fixture at student presentations and design gatherings. With his wife, Judith Ramquist, by his side, he was often the first to say a word of encouragement to a nervous presenter and commend them afterwards.

Making design relatable

Caplan’s ability to make design relatable was a quality that many corporations sought in a writer. After his job at ID, he became a trusted consultant to organizations like the Eames Office, IBM, Westinghouse, and Herman Miller.

“I liked his writing, it was particular and to the point,” says Steve Frykholm, former creative director of Herman Miller, who worked closely with Caplan for more than 25 years. Based in Grand Rapids, Michigan, he particularly cherished meeting Caplan in New York City. “You were always the center of his attention when you were with him,” he recalls.

Many designers influenced by Caplan are going back to their bookshelves and rereading his books and articles for solace now. “By Design (Caplan’s 1982 book) is the bible of design for many of us,” Birsel says. “In it, Ralph talks about something his father said: ‘Did you ever notice that the best comedians never tell jokes? They create funny situations.’ Ralph, like the best comedians, created situations about design, and used humor to make us understand his point. In talking about shoe design, he explained that if a visitor from outer space looked at men’s and women’s shoes, he would assume they were for two different species.”

Frykholm says he’s been perusing the 1976 Herman Miller monograph that Caplan wrote and is rereading a back issue of a journal in which Herman Miller brochures were featured. “I was thinking, ‘Why didn’t I credit the writers?’ In my mind, they were just as important to a piece of communication as the designers.”

Molly Heintz, another former student of Caplan’s who now helms the Design Research graduate program at the School of Visual Arts, says his words are particularly resonant today amid the clamor for racial equality around the world. “I was thinking back to our class many years ago, when Ralph referenced the 1960s lunch counter sit-in at Woolworth’s in Greensboro, NC, as the best example of 20th century situation design,” she wrote via email to the program’s alumni. “Our society in the US has not evolved enough since 1960. I personally am committing to take a more active role in anti-racist and inclusive change and am committing our department to the same.”