It’ll take more than a pandemic to break down Delhi’s beloved Metro system

If you’d asked a resident of India’s capital in January if the city could do without the Delhi Metro, the answer would have been an emphatic “no.” And yet, residents have been managing for over three months without their beloved mass-transit network, shut since March 22 because of the coronavirus.

If you’d asked a resident of India’s capital in January if the city could do without the Delhi Metro, the answer would have been an emphatic “no.” And yet, residents have been managing for over three months without their beloved mass-transit network, shut since March 22 because of the coronavirus.

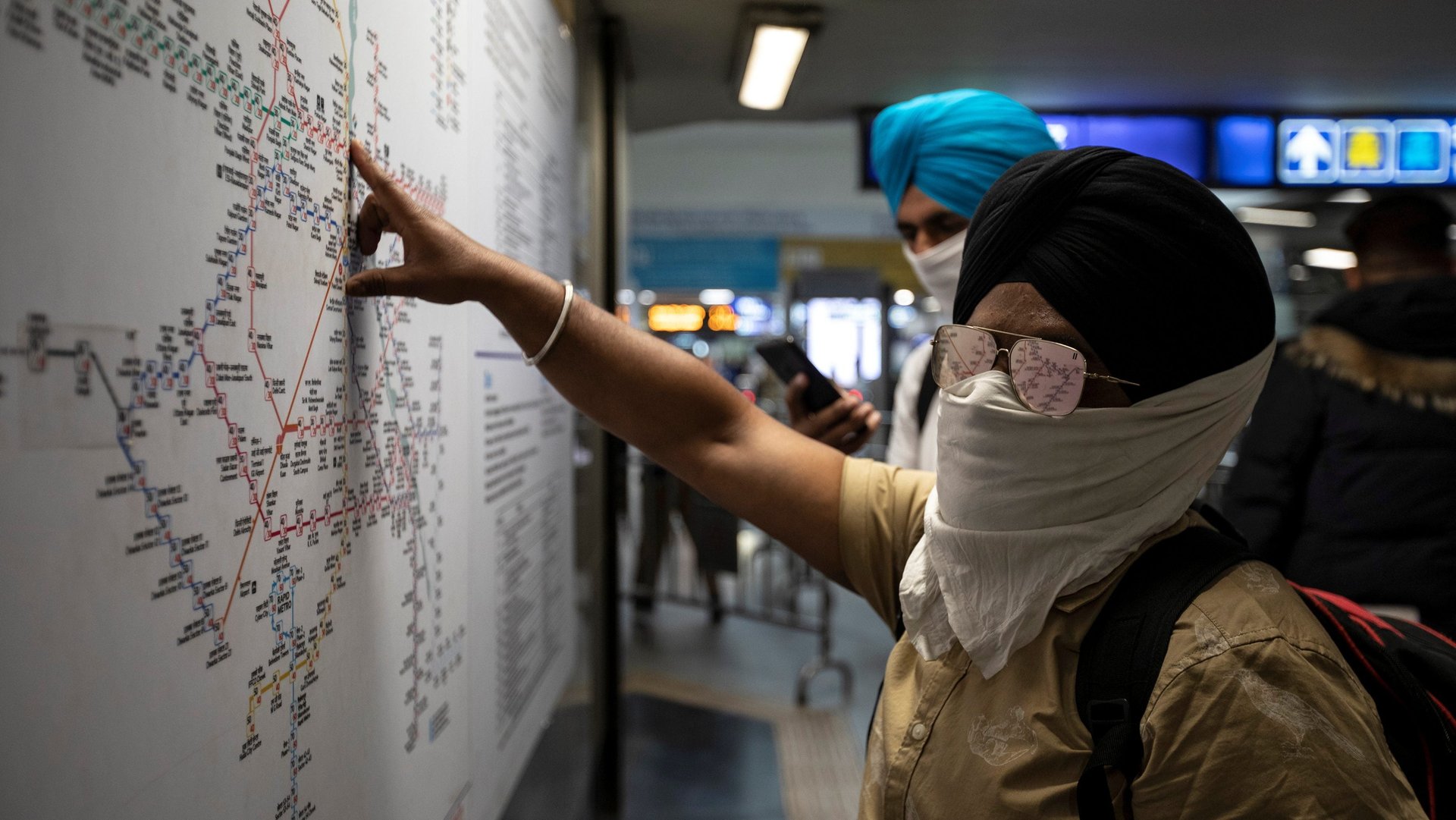

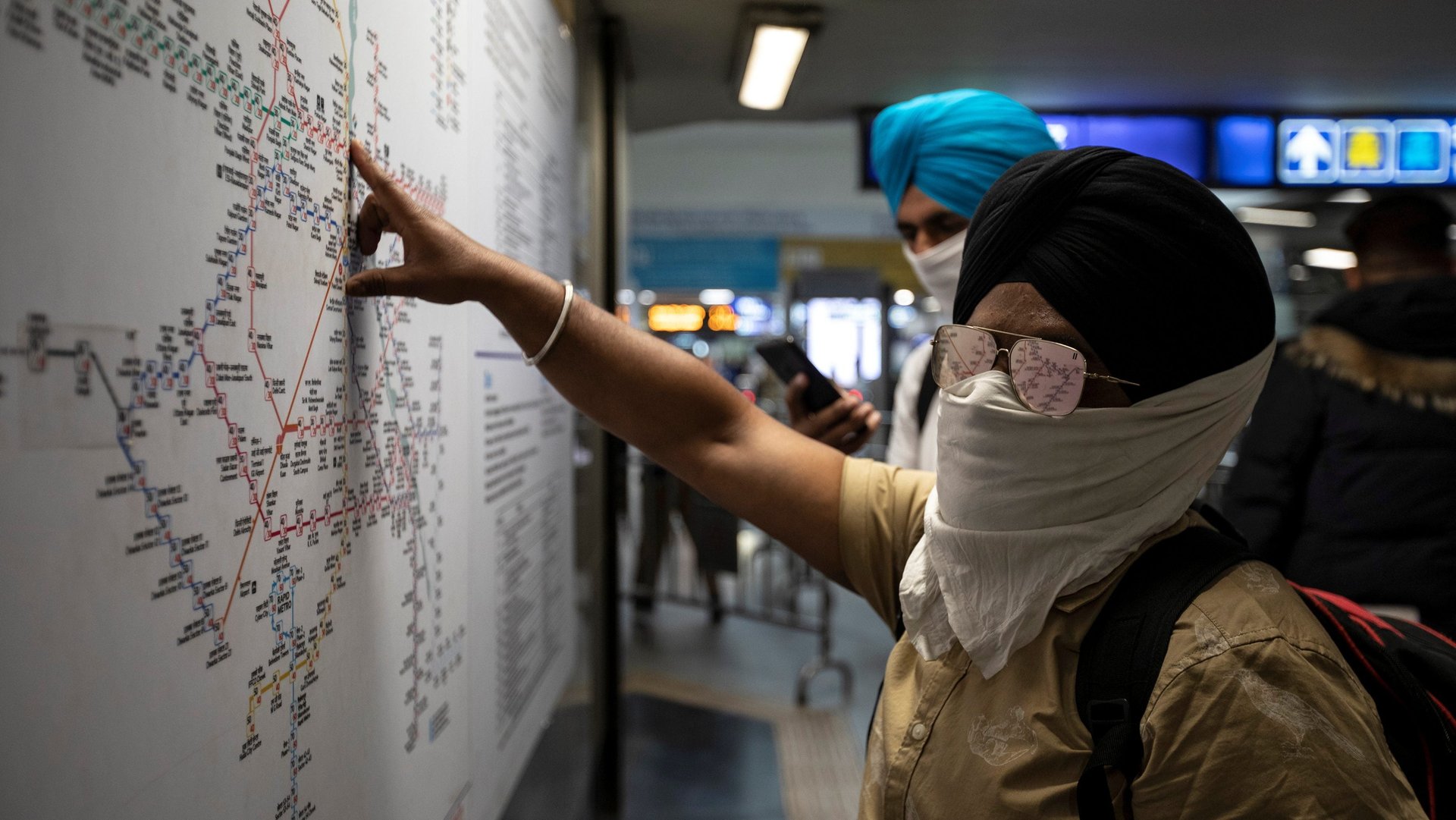

As life limps back to normal and shops and offices open up, the Metro still has to work out its safety protocols in order to restart safely as Delhi, with the highest case count of any city in India, tries to contain the spread of Covid-19. Some of the Metro’s most attractive features now pose a challenge—its air-conditioning has been a boon in Delhi’s fiery summers, but is now seen as a big risk because it increases the chances of the virus remaining and circulating in coaches.

Maintaining social distancing at stations could also be a nightmare given the trains carry 4.6 million people a day, leading to people squeezing past one another to get in and out of coaches, as well as serpentine queues at security checkpoints at rush hour. Those would only become worse if commuters have to go through an additional layer of screening for Covid-19 symptoms.

While urban experts believe that the impact on ridership from the coronavirus pandemic won’t be lasting, the temporary vacuum left by the Metro is offering the capital a needed reminder to pay more attention to other types of transport. Despite long being viewed as a less safe and far less comfortable mode of transportation, buses were quickly cleared for public use once lockdown restrictions began lifting in April, as authorities found it fairly simple to limit the number of commuters in each vehicle and ensure social distancing at stops.

“All of this is perhaps a stop-gap till the vaccine comes,” Rahul Srivastava, a Mumbai-based urbanologist and co-founder of design planning and research collective urbz, and The Institute of Urbanology. “But this could be a time to view public transport as civic infrastructure, relying on many modes rather than just one energy-intensive system of transport.”

Public transport for the middle-class

The first Delhi Metro train carrying passengers set off on Dec. 25, 2002, and traveled just 8.5 kilometers (5 miles). From that short sprint, with the help of financing from Japan, it grew into a network of nearly 300 stations covering 389 km including stops in the satellite towns of Gurugram and Noida—making for a modern, gleaming marvel in an ancient city. The “Metro Man,” overseeing this expansion, former railways civil engineer E Sreedharan, became widely admired for sticking to budgets and schedules.

“The Delhi Metro’s success has been celebrated by almost everyone from ordinary citizens to experts,” says Srivastava. “Delhi witnessed for the first time public transport that came with certainty… unlike Mumbai that has had its local trains for over 150 years.”

The government-owned Metro offered a level of comfort and efficiency far greater than that of state-run buses, which were cheap but not always reliable because of congested roads. Private buses and motorized rickshaws came with added worries—a fatal rape on a bus in the capital in 2012 underscored the dangers of bus travel for women in particular. In contrast, the Metro’s women-only coaches have been a boon for female commuters. The system’s safety—it’s guarded by a federal police force—and cleanliness have played a huge role in elevating the public transport experience of many Delhi residents.

Delhi’s success has also been instructive for other cities, with Jaipur, Bengaluru, Lucknow, and even Mumbai building their own systems. The Indian government aims to have metro rail connectivity in 15 cities by 2025. But despite its immense popularity, one of the biggest critiques against the metro is that billions of dollars have been spent to build a service that is far too expensive for most of the capital’s 30 million people.

“The Metro has had a positive impact on the lives of women and middle-class travelers. But it doesn’t serve the poor,” says Madhav Pai, executive director at the WRI India Ross Center for Sustainable Cities think tank.

Its users are mostly young and middle class—since the metro is far more expensive than taking the bus. An average bus trip costs Rs11 versus Rs29 for a typical metro ride. And a long one-way journey can cost Rs80, or more than a dollar, in a country where per daily capita income is just $6.

Some urbanists also believe it’s promoting a flawed living model for Delhi, eroding a sense of neighborhood. “The Metro has connected far-off places to each other in cities where it is now spreading its tentacles,” says architect Gautam Bhatia. “When where you work, live, and play are far away from each other, it destroys the fabric of a city.”

More buses—and more private vehicles?

Before the rail service, the Delhi Transport Corporations’ (DTC) buses were the city’s lifelines. But the policy focus on the Metro became a death knell for other modes of public transport in Delhi. Today, Delhi has just over 50% of the 11,000 buses it says it needs—a deficit that has existed for several years now. The gap was compounded by the fact that as dangerous private buses were phased out, they were never replaced.

In March this year, the capital finally got its first new buses in a decade, and the government is promising thousands more by next year.

Given the Metro’s longstanding issues with last-mile connectivity, it could only benefit by integrating far better than it does with buses and other kinds of transport. The DTC’s feeder buses were to fix this problem, but that collaboration between the Delhi Metro, and the state-run bus service never reached adequate scale. This, in particular, is the metro’s failing as it operates as a quasi-private entity, rather than working together with other transport systems and land authorities to optimize its potential.

The Delhi Metro didn’t respond to a request for an interview for the story.

Public transport experts also note that even as the transit network grew, traffic has worsened—and so has pollution. Private car and motorcycle ownership in Delhi rose by 4-9% every year from 2014 to 2019.

The city now has over 600 vehicles per 1,000 people, far higher than the national average of 22. The longer Covid-19 drags on, the more likely it is that people in the capital will turn to private modes of travel for safety.

While the economic slowdown might make it harder to buy new cars and bikes, car dealerships and platforms have greater demand for pre-owned vehicles.

Nevertheless, the metro is continuing to expand. Pai, though, believes the system has reached the stage of diminishing returns. “A new line is not going to bring as many benefits,” he says.