San Francisco is using “tactical urbanism” to dethrone cars

The train lines serving downtown San Francisco are nearly empty, cruising beneath mostly shuttered skyscrapers and wind-swept streets. Workers who normally ascend escalators by the thousands during rush-hour commutes are virtually absent. Through thousands of small decisions, San Francisco, one of America’s wealthiest cities, had designed its public transportation around serving white-collar workers. Since the coronavirus pandemic struck, they’re nearly absent.

The train lines serving downtown San Francisco are nearly empty, cruising beneath mostly shuttered skyscrapers and wind-swept streets. Workers who normally ascend escalators by the thousands during rush-hour commutes are virtually absent. Through thousands of small decisions, San Francisco, one of America’s wealthiest cities, had designed its public transportation around serving white-collar workers. Since the coronavirus pandemic struck, they’re nearly absent.

“Our transit system was oriented around our financial district,” says Jeffrey Tumlin, director of San Francisco’s transit agency, MUNI. “Covid has revealed the geography of our essential workers.”

A few blocks away, the buses and trains serving the city’s Chinatown are often full. The 14 MUNI bus leaving Excelsior, home to many of the city’s Hispanic residents, hums with people mostly wearing masks (by city order). Destinations in its outer, less expensive neighborhoods still bustle compared to the desolation downtown as workers head to hospitals, restaurants and other essential businesses from their more modest homes perched on San Francisco’s steep hillsides.

The coronavirus pandemic is rewriting who rides transit, and where they go. Historically, transit agencies have focused on delivering white-collar professionals downtown, often at the expense of lower-income residents who need better access to jobs. Transportation consultant Jarrett Walker argues the systems serve people who look like those running them, known as “choice riders,” rather than the low-income riders with few other options. This elite projection, argues Walker, “is perhaps the single most comprehensive barrier to prosperous, just, and liberating cities.”

Now that ridership has dropped by as much as 90% in major US metros, all those empty seats are giving cities a chance to ponder their identity: who do they serve and why?

A new model is emerging, one that weaves together transit and micro-mobility options, with personal vehicles on the outside, and underserved communities at the center. This approach optimizes what transit does best: funneling as many people through central routes as efficiently as possible, even if that means sacrificing some direct services. To compensate, cities are multiplying the options people need to access these main lines—without cars. This means measures as unglamorous as rapid buses, but also closing roads to cars, subsidizing car-sharing, authorizing fleets of electric vehicles, and other novel experiments now underway.

Soon, advocates say, you’ll be able to walk out the door, catch a scooter, grab the subway and pedal your last half mile to work having booked every leg of your commute on a smartphone app.

But US transit agencies still need to sell this vision, and pay for it. In San Francisco, the transit agency was projecting a $66 million budget deficit before the pandemic this January. Now that’s expected to grow to $200 million this year. City leaders are fighting over to raise fares or find new revenue streams: “One thing we’ve been very clear on is we will not raise fares on struggling San Franciscans,” said one city supervisor.

The pandemic has opened the doors for change. The crisis will be a test of what cities want to become. That is leading to “tactical urbanism,” part of the greatest wave of experiments in urban design in half a century.

How we got here

Since the mid-20th century, most Americans have lived in a dystopic version of a city first publicized by General Motors. During the 1939 World’s Fair, GM’s Futurama gave the public a vision of huge urban thoroughfares under towering buildings that whisked drivers to areas sharply divided between residential, commercial, and industrial. Banished to the urban perimeter were “undesirable” districts and “slum areas.” GM’s vision has turned into massive gridlock. Since the 1980s, the number of hours American spend in traffic has nearly tripled, with Americans now spending nearly 99 hours per year in traffic. Cities are now spending billions of dollars to try and undo this, says urban policy researcher David Zipper, a fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School.

It won’t be easy. The obsession with getting as many cars down roads as quickly as possible has profoundly shaped the layout of cities and government budgets. The US has historically spent about 70% of its transportation funding on highways and only 20% on transit. Almost nothing, relatively speaking, is allocated for walking and biking. Transit, when it exists, is often an urban afterthought with limited service for commuters and even less for the car-less. It is also chronically underfunded. Mass transit only covers about a quarter of its expenses with fares, which average around $1.20 per trip. With ridership collapsing, transit agencies now face a yawning revenue gap between $4.2 billion and $8.1 billion through 2021, almost 10% of total spending, according to the American Public Transportation Association.

The shortfall threatens to exacerbate inequities in an already unequal system. As good jobs have migrated to cities, long commutes and rising housing prices have excluded those seeking to escape poverty. And few things are as important as transportation. In New York City, unemployment and lower incomes are linked to poor transit access. A 2015 Harvard University study found shorter commuting times are better predictors of communities’ upward mobility than elementary-school test scores or the share of two-parent households.

To deliver on the promise of public transit, the systems will need to be reimagined. San Francisco, always searching for what’s new, is a good place to look.

The San Francisco case

Few places are on the front-lines of change like the Bay Area, home to Silicon Valley. Uber launched there in 2010. Lyft’s giant pink mustaches began appearing on car hoods two years later. Since then, a deluge of transportation options have filled the streets. A stroll down San Francisco’s main drag, Market Street, is a glimpse into an electric future. It was closed to most private cars this January as part of the city’s transit-first strategy. Hoodie-wearing tech workers steer Lime scooters next to electric skateboards and precariously balanced one-wheelers. Cyclists on e-bikes from the hip Mission district ride alongside vintage streetcars, rescued from defunct 20th-century transit systems. New exotic electric conveyances arrive each year.

But this belies a system that wasn’t working all that well, especially for those in distant lower-income neighborhoods. During peak hours, subway, rail and bus lines have been strained past the breaking point. To the south, in the heart of Silicon Valley, limited rail options and low-density housing has led to traffic congestion even worse than in Los Angeles. Once the economy reopens, San Francisco is most at risk among US cities for even more crushing delays, estimates Will Barbour, a transportation research scientist at Vanderbilt University. If transit systems can’t restore original capacity, delays of 20 to 80 extra minutes per trip are expected. “Mobility is the primary constraint for further economic recovery,” admits Tumlin.

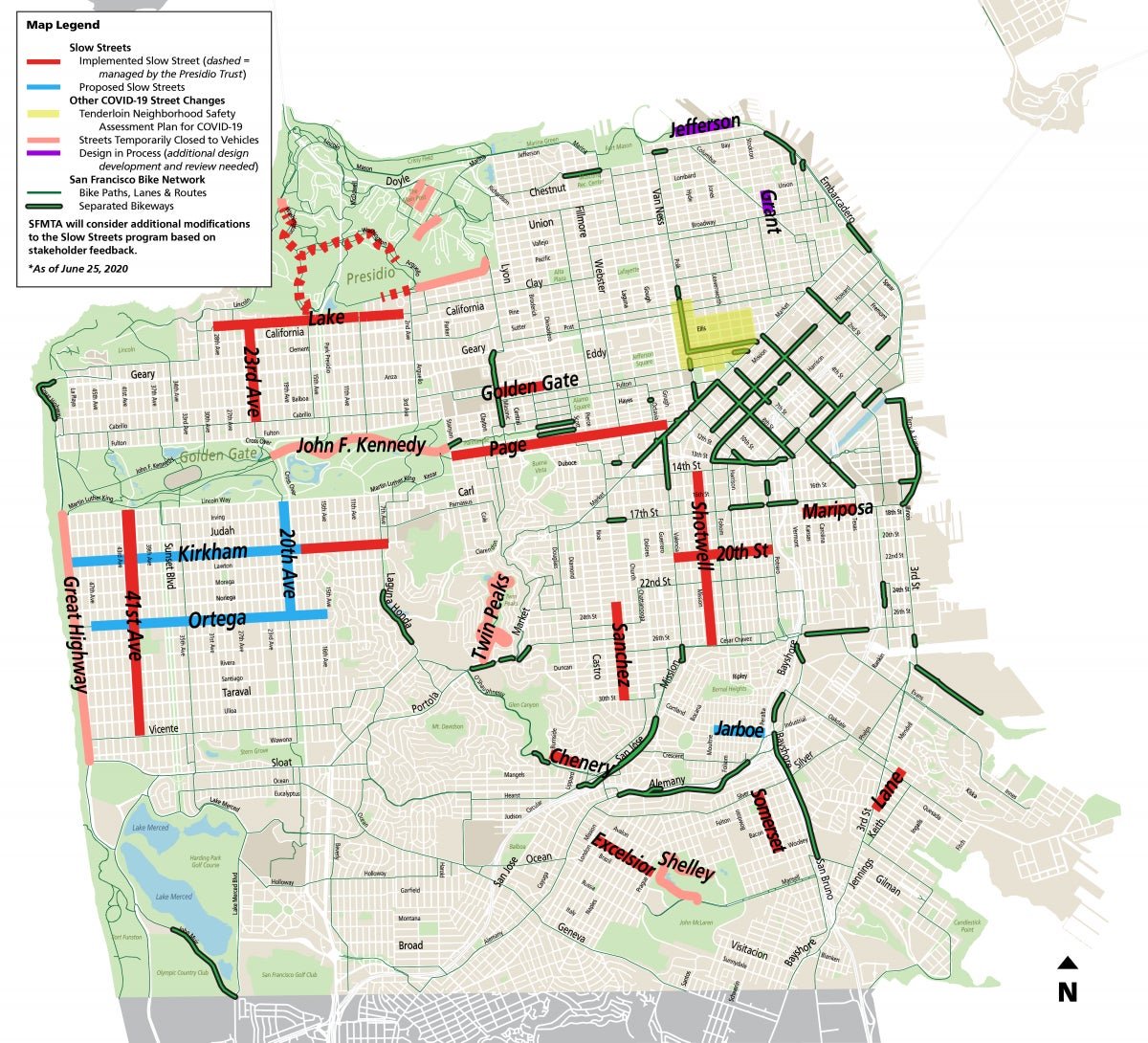

That’s initiated the largest urban transportation experiment in a generation. San Francisco transit officials are embracing “tactical urbanism.” Instead of years of planning, they’re adopting fast, light-weight solutions laying the groundwork for future changes. New bus stops are being erected overnight with cans of paint and plastic. San Francisco has designated 24 miles as “slow streets,” which limit traffic on residential streets for bikes and pedestrians, as well as new bike lanes to handle new riders using personal bikes and the city’s multiple bikeshare programs. Ten more miles are now scheduled.

The city is repurposing sidewalks and parking spaces for outdoor dining, and public gathering spaces. It has pushed through a politically fraught rerouting of its train system that would have been impossible pre-pandemic. Its Covid-19 core system fast-tracks buses from outer neighborhoods, while halting some direct light-rail routes in inner neighborhoods. Those measures reduce overall wait times and overcrowding, according to MUNI, improving the equity of the system in neighborhoods with more low income and minority households, as well as lower private vehicle ownership.

That’s phase one, focused on the core. The next phase is expanding partnerships at the perimeter. Unlike the heavy infrastructure for rail stations and bus stops, the private sector can easily step in to handle first- and last-mile connections. San Francisco recently signed a contract with Lyft to provide 8,500 bikes, effectively doubling its fleet, and numerous electric scooter startups already operate in the city. Twenty thousand critical workers were given free annual Citi Bike memberships by Lyft.

Vehicles are increasingly being drawn into the equation as well. Ride-hailing services want to serve as a transit extension by doing what backbone rail and bus lines often do not: provide flexible suburban, paratransit, and last-mile services. Lyft has already integrated transit routes into its app, announcing more than 80 transit partnerships including Miami, St. Louis, and Carson, CA. In neighboring Marin county, Uber is doing the same. A two-year, $80,000 pilot for Marin Connect will give the country’s residents access to four wheelchair-accessible vans in the Uber app, as well as vouchers for rides from transit stops. It’s the first stop before opening up its ride-hailing service as a long-term contract with transit agencies around the world.

Change is afoot outside the Bay Area, too. The US government is taking a second look at walking and biking: the bi-partisan Bicycle Commuter Act would give commuters tax benefits of up to up to $54 per month to cover their commuting costs on bikes, e-bikes, and bike-sharing memberships.

This ferment is giving cities a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reimagine themselves, says Warren Logan, head of Oakland’s Department of Transportation. “For the first time, all-star teams in government are working on it,” he says. “The pandemic has given us a blank canvas to make radical changes.” And, he notes, they are responding to the needs of riders who have rarely had a voice: lower-income workers, many deemed essential during the pandemic. This time, he says, cities have a license to try things that would be off the table in normal times, and a willingness to reorient their cities toward more equitable growth.

Tiffany Chu, founder of the urban mobility planning startup Remix, sees this every day in her work with 325 cities around the globe. This spring, New York launched an overnight bus service for essential workers over a weekend. Española, New Mexico rerouted their entire system without furloughing a single operator. Krakow, Poland designed completely new routes dedicated to hospital staff. And many, many others.

These transit initiatives can’t rectify urban inequality on their own. Improving transit options in a neighborhood can make it more attractive to live in, which can mean higher rents and gentrification. Experiments in transit equity are therefore dependent, in part, on housing policy. But the momentum and the appetite for experimentation are higher than they’ve been in a lifetime. “Almost every transit agency is fast-tracking something and making a ton of changes right now,” Chu says. “We’re seeing it happen every day.”