I took an online class—and actually liked it

Ever since massive open online courses (MOOCs) were launched, essay after essay has been published on how they are disappointing, what could be improved, and what will never be attained. It is my impression that many of the people who write about MOOCs have never taken nor designed one. Perhaps they work in academia, or perhaps they observe it from outside—the ultimate of ironies because commenting on the world as observed from the outside is the very definition of academia.

Ever since massive open online courses (MOOCs) were launched, essay after essay has been published on how they are disappointing, what could be improved, and what will never be attained. It is my impression that many of the people who write about MOOCs have never taken nor designed one. Perhaps they work in academia, or perhaps they observe it from outside—the ultimate of ironies because commenting on the world as observed from the outside is the very definition of academia.

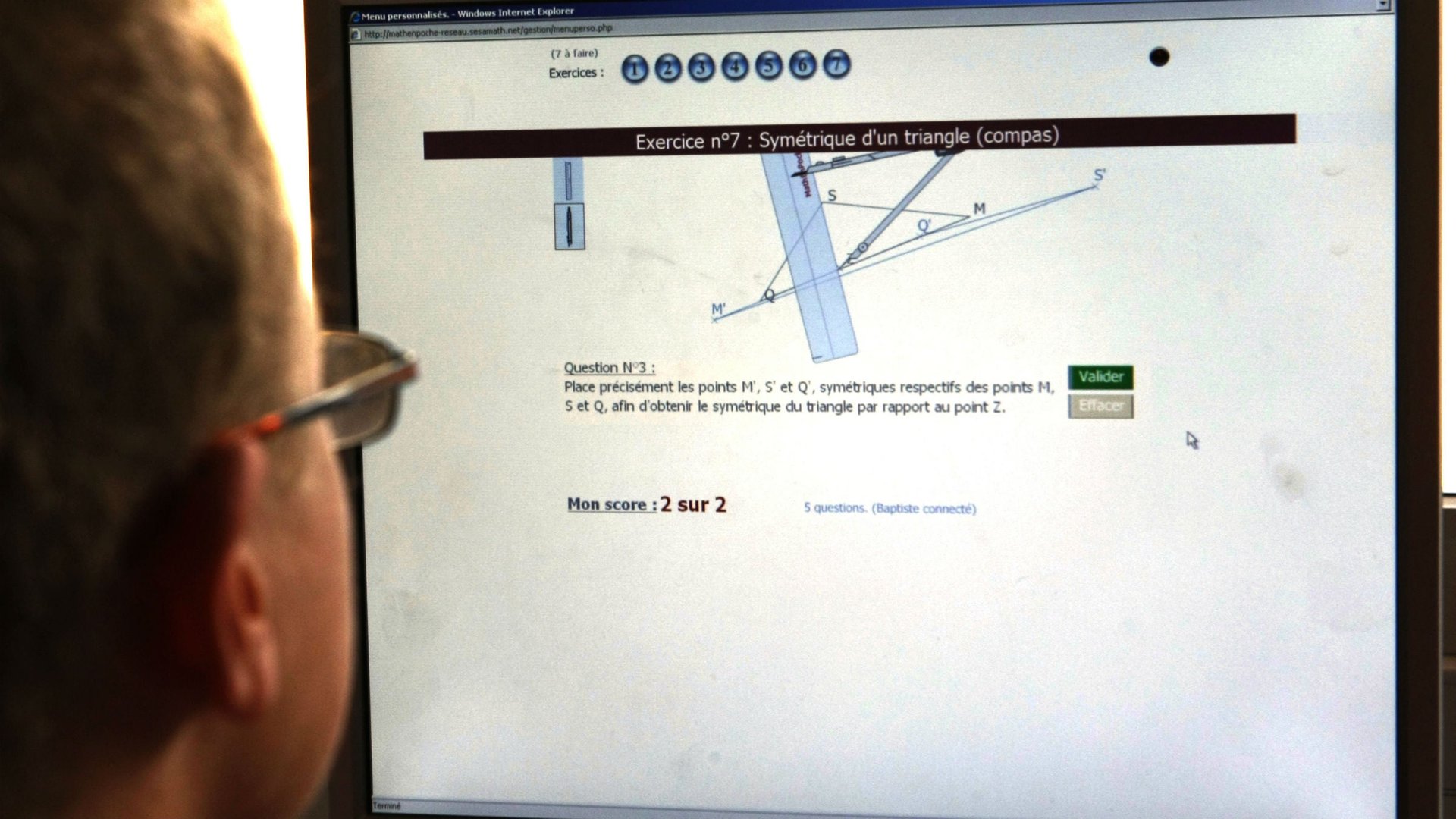

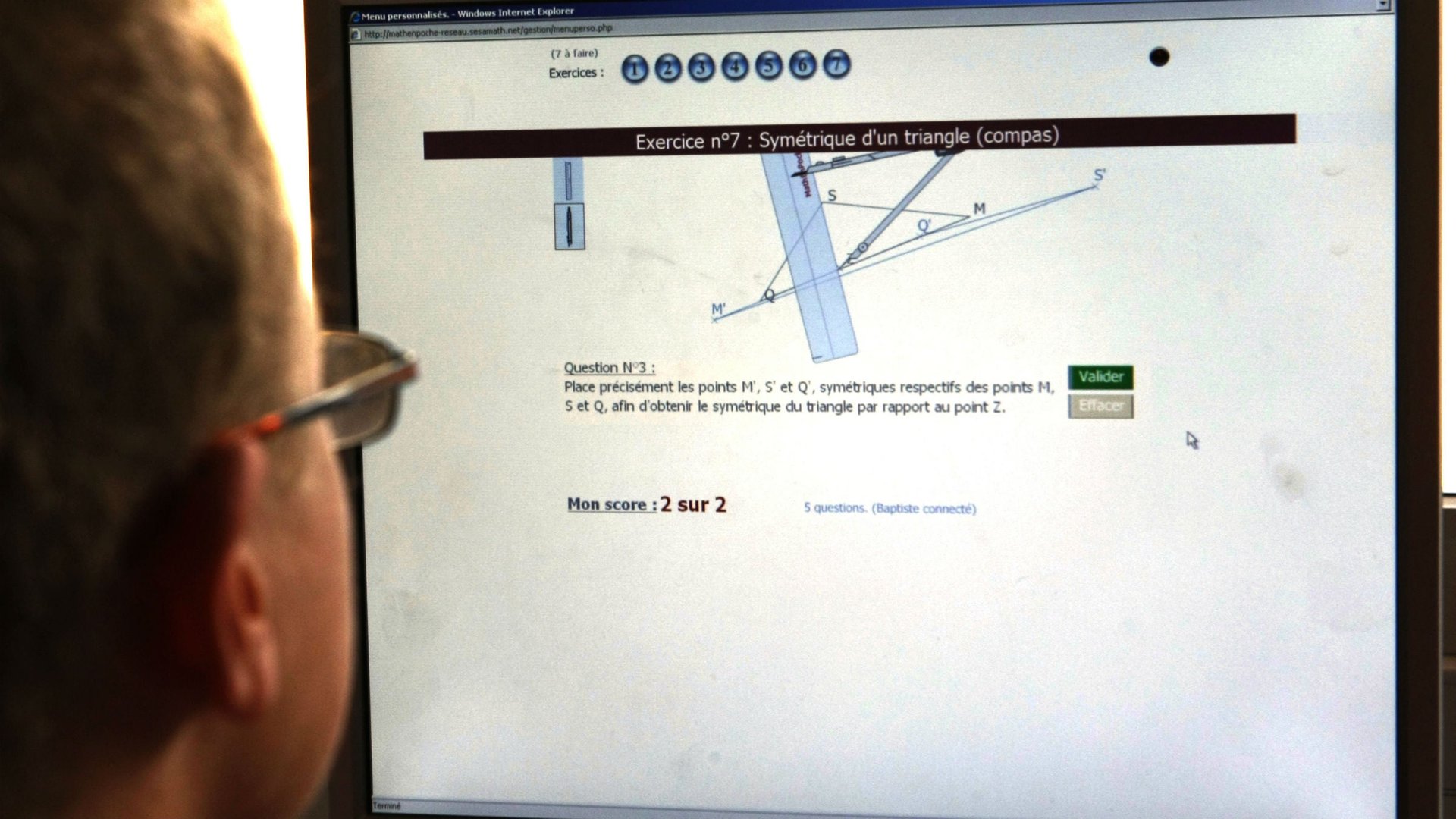

I did take a MOOC though—about data visualization, taught by Alberto Cairo at the Knight Center for Journalism at the University of Austin, Texas. And I liked it.

MOOCs may not have revolutionized the world of education. Yet. But they are introducing important and necessary changes. Judging their success based on old parameters, comparing them to what classrooms used to be and schools used to do, seems unfair and a bit pointless—because you can’t measure innovation based on the metric of what already exists. In about two years, MOOCs have already become ubiquitous, and the world of education has had to quickly adapt to include them: the advantages they bring can’t be measured by comparison with traditional courses, which run on much higher resources and smaller numbers of students. It’s a different paradigm. Here’s why they work:

Because learning

Education is—where more, where less—elitist and transactional. If you can afford it, see its importance, dedicate time to it, and put in effort and money. In exchange, you get certificates. Some form of laisse passer to where you want to be when you grow up.

Online courses help extend universities beyond the transaction. Yes, they are available to those who can’t get access—for financial, or spatial, temporal reasons— to college, but also to those who work full time, or who already have high degrees or just happen to be curious about new subjects but can’t justify or face the cost of classes they don’t need.

Many of these people aren’t necessarily going to use the knowledge they acquire in a MOOC as a market currency. So here’s the first innovation that open online courses represent: learning for learning’s sake.

Old school is the new school

Even MOOCs that are offered as an alternative, or a complement, to traditional classes could work well. Much criticism of MOOCs assumes that all universities work the way American universities do—top-notch infrastructure, small classes, engaging professors, and scrupulous students.

That’s not how the rest of the world works. I studied in Italy, at the University of Bologna, where the maximum cost of one year of undergraduate study is €2,573 ($3,566)—and not much has gone in the way of innovation when it comes to studying. Many of the classes I ever attended had well over 100 students (sometimes several hundred), and professors wouldn’t often assign readings, encourage debates, check that we were up to date with studying. There were lessons, notes, lots of books to read, and finals (none of which were open book). We rarely got to write and present papers, and even more rarely worked in groups. There were no introduction weeks, no course advisors (which does not mean professors would not give advice), and you had to figure most things out on your own.

I am not going to argue whether it’s a better or worse model —it’s probably a bit of both—but it sure is cheaper. Now, under the scenario of my one-size-fits-most education, what would really change if MOOCs truly became an alternative to showing up for classes? A lot more people would be able to attend. Furthermore, it would expand options for students: allowing them, for example, to follow courses from partner universities, or in different languages, even if they can’t afford the cost of traveling for a semester abroad.

Easy in, easy out

True, many people drop out or don’t finish the courses. Quartz contributor Todd Tauber points out that more than 90% of the students enrolling in MOOCs don’t finish their classes. So what? If it weren’t that following classes has a quantifiable objective—getting a degree, and then hopefully a job—would it be such a big deal if students abandoned the courses they weren’t interested in following? Wouldn’t the dropout ratio force professors to make their lessons more engaging? Plus—for a little Darwinism—if it’s so easy to drop out from online classes, than those who advance are those who show more commitment.

The internet can’t stop, won’t stop

We know better than to try to stop the internet. Connectivity democratizes, especially information. It forces access (slowly but surely, starting with the haves but eventually reaching the have-nots): temporally, spatially, and financially.

Online courses are not a panacea: the ideal is in-person instruction, free of charge, to everyone, everywhere. It’s a ways off.

In the meantime, there are MOOCs.

Take a second to be amazed at what that still represents for most people in most places: whatever new subject you happen to be curious about, there is probably a free online course out there to take, on your schedule. The people complaining about this feat, this possibility, seem the same sort to complain that the internet connection on their plane is slow. But sometimes, it’s okay to wow before we whine.