Crisis looms for 50 million parents as US states decide how to handle the school year

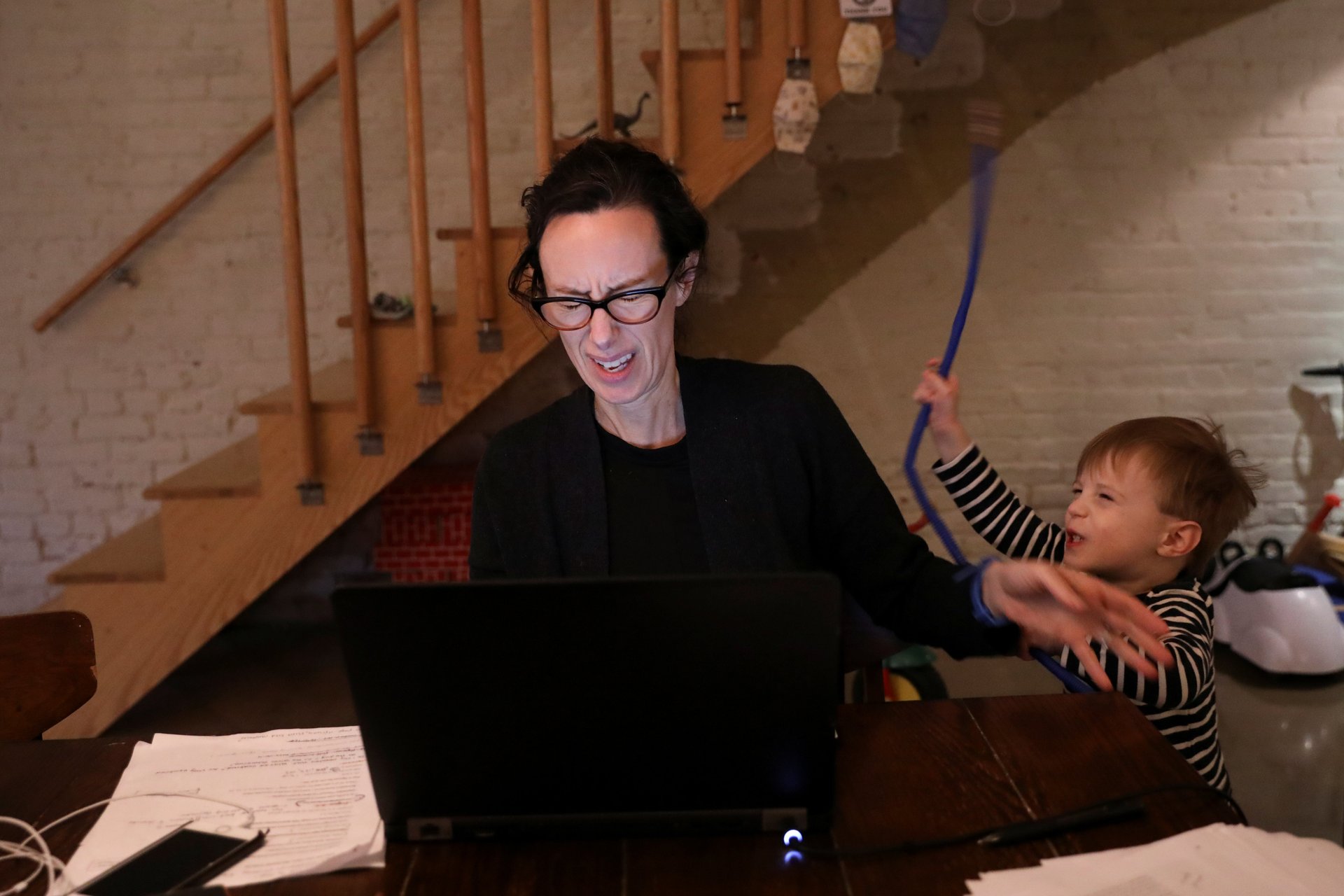

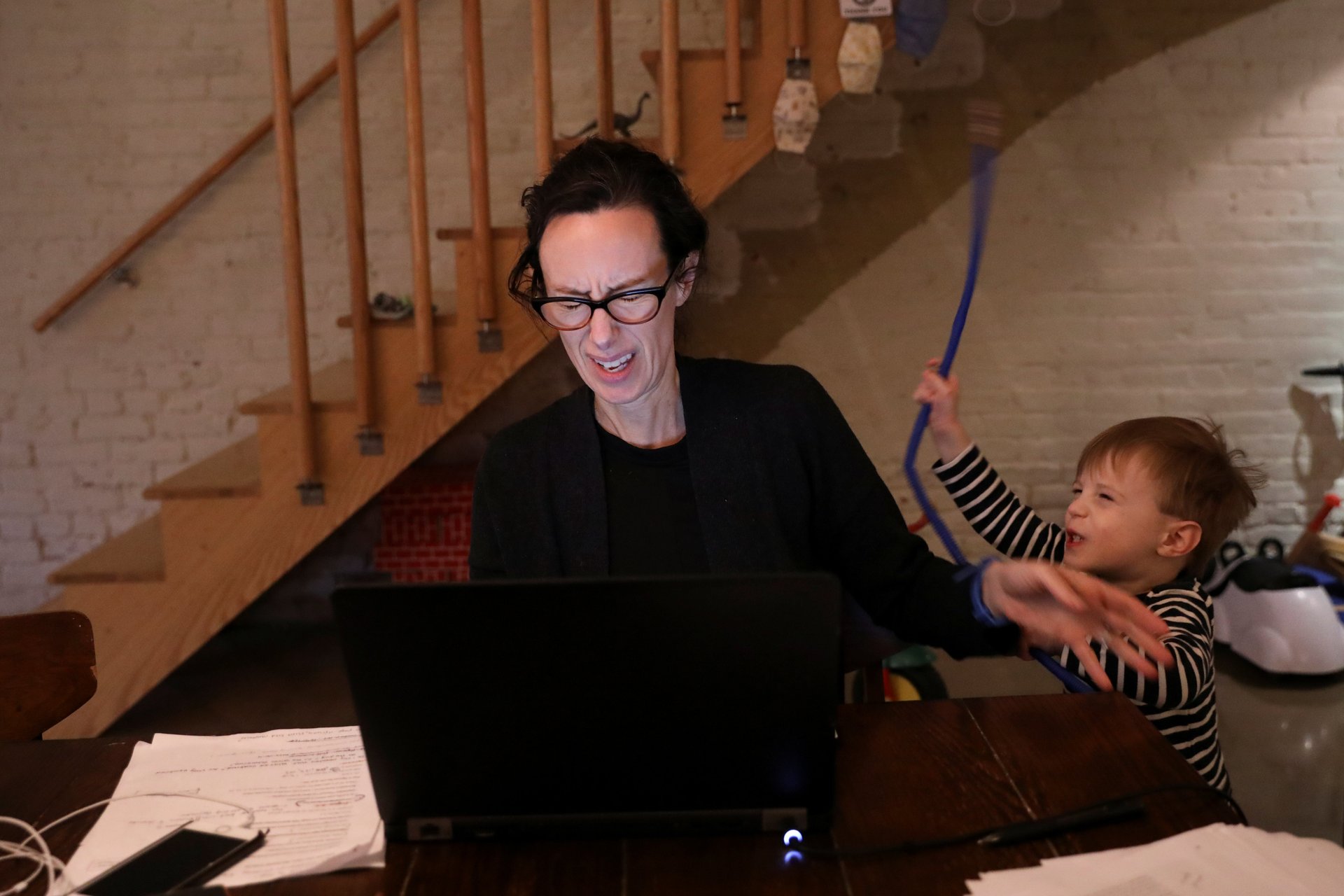

American parents stand to lose even more productivity—and their minds—as more school districts like Los Angeles limit how many students will return to the classroom for the upcoming school year. This situation could weaken recovery efforts over the long term.

American parents stand to lose even more productivity—and their minds—as more school districts like Los Angeles limit how many students will return to the classroom for the upcoming school year. This situation could weaken recovery efforts over the long term.

People living with children under the age of 14 were 32% of the US workforce in 2018, according to an analysis of US Census data by the Becker Friedman Institute at the University of Chicago. That means 50 million workers would need to figure out what to do with their children if workplaces open before schools and day care facilities.

According to the study, while some of those families have a stay-at-home parent, many others don’t: 21% of US workers live in a household without a non-working adult who could take over their childcare duties. In order for every one of those households to have an adult watching the kids, 11% of the workforce would have to stay home.

Virtually all US schools closed in the spring to stop the spread of Covid-19. Many camps and other summer activities have also been cancelled this year. Meanwhile, stay-at-home and social distancing measures are severely reducing other childcare options, like babysitters, nannies, and au-pairs. Families can’t rely as much on grandparents or other older relatives either, especially if one of the parents has an essential position considered high-risk for Covid-19 exposure.

As the start of another school year quickly approaches, working American parents are dealing with the prospect of continuing to juggle child care and full-time jobs. While many white-collar workers have been able to work from home, employees in the retail, hospitality, tourism, manufacturing, and construction industry can’t.

So far, the number of parents pulling back or dropping out of the labor force has been lower than expected, according to economist Elise Gould of the Economic Policy Institute based in Washington, DC. This is because the industries that experienced the greatest job losses—hospitality and retail—employed more young, childless workers.

However, this will likely change in coming months. Gould expects the labor participation rate for parents of young children, especially mothers, to fall as more businesses close again due to a spike in Covid-19 cases across dozens of US states and more school districts switch to virtual learning. More parents might also drop out of the labor force if employers that have allowed flexible work hours and other accommodations start feeling less generous as the pandemic continues.

To properly address this, the federal government should keep its $600 supplement in unemployment insurance, and states should continue eviction moratoriums, Gould said. “Policies should be triggered on and off by economic and health conditions, and not by some random date,” she added.

If schools do plan on opening, Gould said there needs to be more government aid invested into public education to provide resources such as personal protective equipment and additional airflow filtering to increase safety for teachers and students, reducing the possibility of transmission.

Wage stagnation means many parents are already under financial strain despite dual-income households. The pandemic should not force them to choose between childcare responsibilities and their participation in the larger economy, Gould said. “You can’t choose between leaving your three-year-old home alone and going to work,” she added. “They’re super constrained in terms of economic decision-making.”