How a diverse team came up with a dating app designed to combat bias

Dating and relationships are a common conversation topic for many coworkers—but particularly so at S’More, a New York City-based dating app founded last year.

Dating and relationships are a common conversation topic for many coworkers—but particularly so at S’More, a New York City-based dating app founded last year.

The app’s head of operations, Sneha Ramachandran, recalls one eye-opening exchange she had with her teammates about cultural norms surrounding the questions people ask each other on dates. One woman explained that in her home country of South Africa, it’s common to ask early on whether the other person has been tested for HIV. For Ramachandran, who’s originally from India, “if someone asked me that, I would be so offended—that was my bias.”

It was a classic example of how diversity serves as a competitive advantage, allowing colleagues to anticipate and plan for possible reactions from a broad user base.

In S’More’s case, founder and CEO Adam Cohen-Aslatei sought to assemble a team of people from a variety of backgrounds, the better to shape an app with cross-cultural appeal. The startup’s small crew of six full-time employees includes a Black millennial woman from South Africa, a married woman from India, a Filipino-American woman, a white man, and a straight Asian man, along with Cohen-Aslatei himself. There’s also an Asian-American designer, an Indian intern, and an Asian intern.

“At S’More, we have conversations every week about how we feel about sexuality and relationships,” Cohen-Aslatei says. “Those conversations lead to much better products, because we’re considering so many voices.”

The composition of S’More’s team is also central to its mission: To counteract the biases that are rampant in the world of online romance.

The bias of dating app design

Research has shown that Black women and Asian men face particular bias from potential matches while online dating, and that white people are the least inclined to date outside of their race—even if their preferences state otherwise.

Apps themselves often seem to only exacerbate people’s biases. As one 2020 study explained, because the swipe-right model of dating apps like Tinder greatly emphasizes appearance (which necessarily includes race), race “appears to contribute to users’ dating market value, serving as a factor to indicate similarity, and therefore reduce uncertainty about their dateability.”

When design encourages people to make superficial snap judgments, in other words, their unconscious and explicit biases surrounding race kick in; they’ve got little else to go on. Some apps also allow people to set filters for race and ethnicity, a feature that critics say further perpetuates discriminatory tendencies. And apps like Coffee Meets Bagel have come under fire for using algorithms that primarily surface matches with people from the same race.

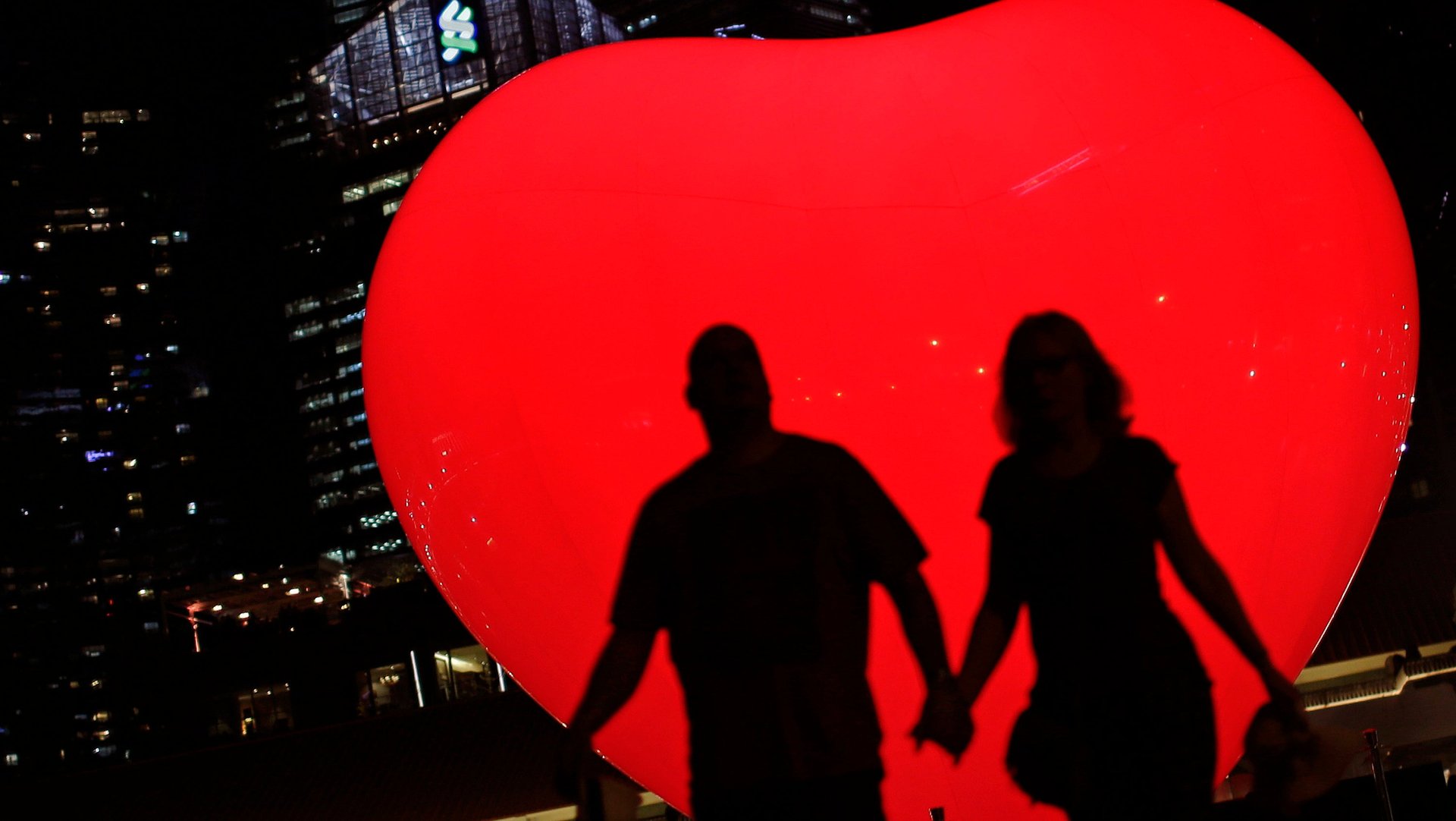

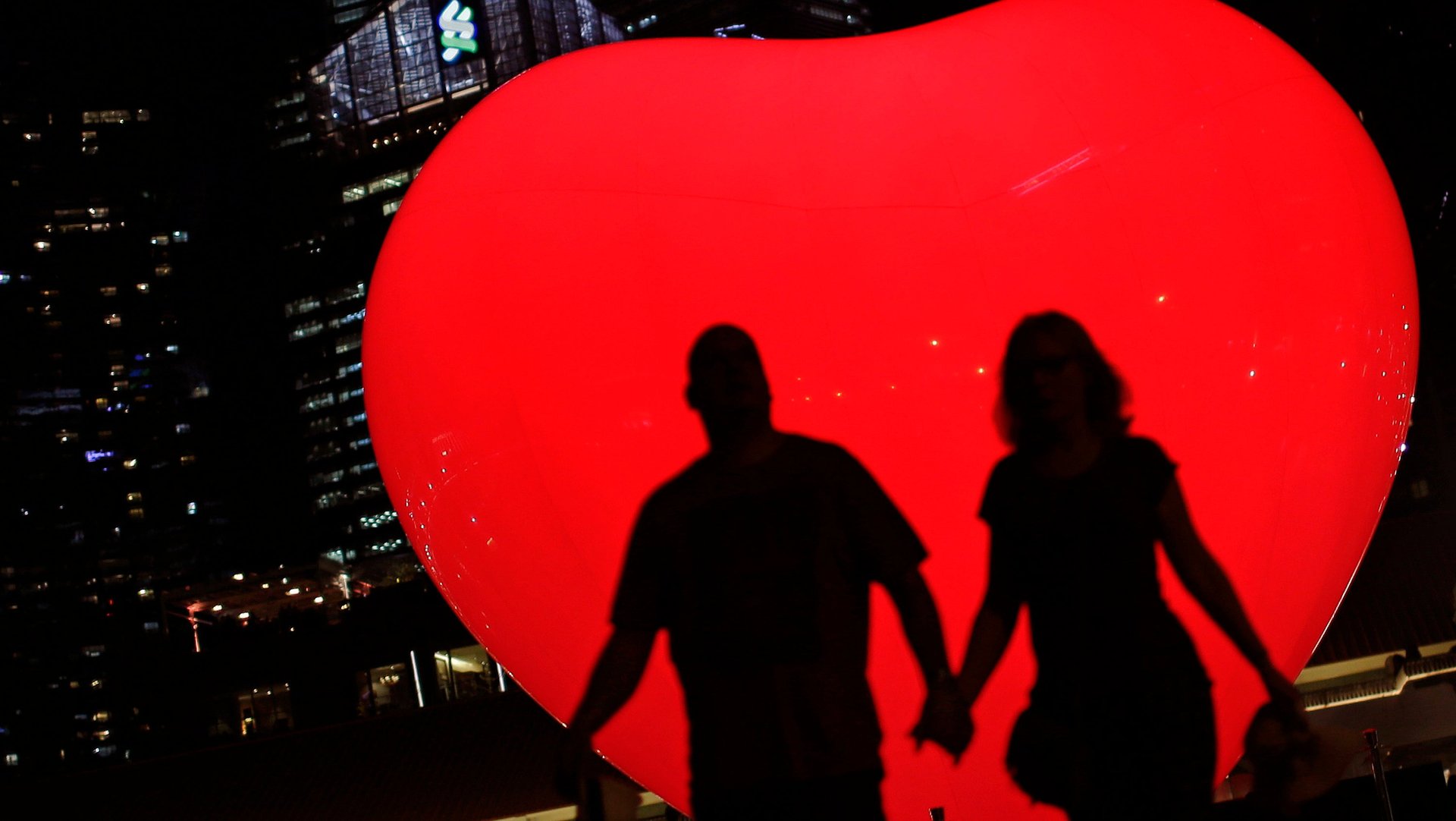

But if dating apps’ design can reinforce prejudice, perhaps they can also be designed to mitigate it. That’s part of the impetus behind S’More, the name of which is both short for “something more” in reference to its efforts to promote deeper connections and a reference to the gooey cookie-and-marshmallow campfire treat. Its design aims to make the online dating process a little less reactive—thereby challenging some of the knee-jerk biases that can inform whether a person swipes left or right.

Against snap judgments

S’More does not offer filters by race or ethnicity and initially blurs the photos on users’ profiles. This is intended to prompt potential matches to instead browse the person’s interests or favorite band.

As users interact with the profile, the photos gradually unblur. People still get to determine whether or not they find the potential match attractive, but the process gets slowed down. Since launching officially in March 2020 after months of developing and testing the app, the company has attracted over 50,000 users across five US cities.

“As a gay Jewish person, I understand people do have cultural preferences,” says Cohen-Aslatei, who previously worked as managing director of the gay dating app Chappy. But, he points out, “there are specific apps to address niche markets,” like J-Date or Muzmatch for people seeking romantic connections with others who observe the same religion.

General dating apps like S’More, Cohen-Aslatei says, are meant to help people focus on shared hobbies and values—like whether a potential match also enjoys running and cooking—not facilitate racial divisions. He attributes the superficiality of many dating-app experiences to the fact that a majority of the people who work at those apps tend to be straight white men. “That’s why a lot of these apps are built for straight men; you can play ‘hot or not’ all day long,” he says.

As another example of how S’More’s diversity has influenced its product, he describes the way the team designed the app’s video dating option. Video dating as a concept has been around for years, but it’s never really taken off—largely, Cohen-Aslatei says, because women were freaked out by the concept of “suddenly having this guy or girl in your home.”

“What we wanted to do is make it more fun and add a layer of safety and security,” he says. For the first two minutes, the video chat is blurred, giving both parties a chance to figure out whether or not they’re comfortable. “If you feel like it’s not going in the right direction, you can leave before showing your home.” As a bonus, it happens to be a convenient feature to offer in the midst of a pandemic.

A culture of difference

At a company where there’s no one dominant racial or ethnic group, Ramachandran says, staffers don’t feel like they’re in the minority expressing themselves or talking about their experiences. “When the team started off, it was so evident in how we worked, how we’d talk in the office, what was important to us, how we’d eat, everything was so different,” she says.

The other thing that distinguishes S’More’s culture, Ramachandran says, is that Cohen-Aslatei actively asks people for their opinions, rather than putting the onus on individuals to come forward with their ideas and perspectives. “Are there tense conversations? Of course,” Sneha says. But the fact that the boss is saying stuff like “I would like to know what you’re thinking, does this make sense?” means that people are a lot more likely to feel that their thoughts are actually welcome—and thus, they’re more likely to be heard.

S’More is still new, and it’s yet to be seen whether it will succeed in nudging users to move past ingrained biases. But research suggests that online dating behavior is malleable. For example, one 2013 study analyzed the messages sent between OkCupid users who chose to self-identify their race. It found that people who received a message from someone outside their own race were then more likely to initiate new inter-racial conversations themselves.

As the researchers behind a 2018 article arguing for anti-discriminatory dating app design explain: “People’s intimate preferences are somewhat fluid, and are shaped both by the options presented to them and through encounters with things they don’t expect.” In other words, dating apps may be able to bolster the anti-racist movement by rewriting the rules of attraction.