The VHS-Betamax war of electric cars is about to be decided

Earth is a single planet divided by dozens of different electrical plug standards. As world travelers (and device manufacturers) know, there is a frustrating babble of incompatible pins, prongs, and plugs out there. As electrification first spread across the globe in the 1900s, no one paid attention to making them all work together. When a global standard finally arrived in 1986—the Type N—it came far too late: Only Brazil and South Africa have adopted it.

Earth is a single planet divided by dozens of different electrical plug standards. As world travelers (and device manufacturers) know, there is a frustrating babble of incompatible pins, prongs, and plugs out there. As electrification first spread across the globe in the 1900s, no one paid attention to making them all work together. When a global standard finally arrived in 1986—the Type N—it came far too late: Only Brazil and South Africa have adopted it.

Now the world has a second chance to get it right. The next great electric revolution will put 120 million electric vehicles (EVs) on the road in the next 10 years. McKinsey, a consulting firm, estimates 40 million chargers will be needed in China, Europe, and the United States to support them, a $50 billion investment. In the age of globalization, the market must escape the same maze of adapters that beleaguered the first wave of electrification.

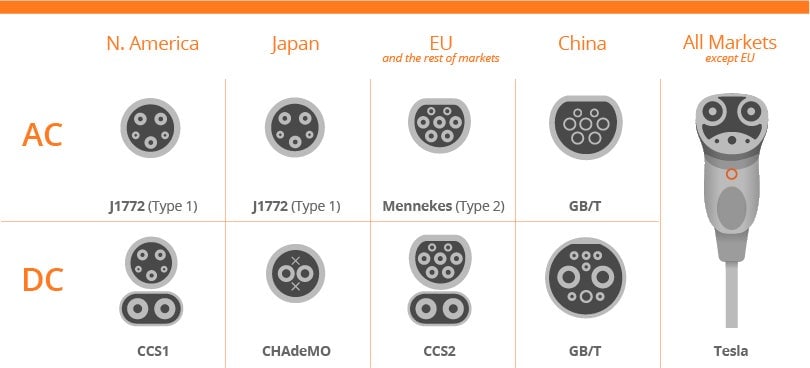

“EVs are still in early stages of the VHS-Betamax rivalry,” says Ramteen Sioshansi, an engineering professor at Ohio State University. Energy services firm Enel X reports there are now nine major EV connectors around the world, often several in the same country. Each is slightly different.

North America has begun consolidating around a common standard, called J1772, and related CCS1 for fast charging, but has several others. The EU has chosen Mennekes and CCS2. Japan (Chademo) and China (GB/T) each have their own. Tesla designed its proprietary system to work around the world for Tesla owners. Adapters allow some of these to work together, but not all.

It’s a bit of a mess. The plethora of different shapes, plugs, and voltages emerged from a combination of legacy electrical systems and off-the-shelf parts first used to construct EVs, says Henrik Holland, the chief operating officer of EV charging firm Greenlots. Home charging works well within regions. But fast-charging remains a polyglot of different standards.

Functionally, the plug standards vary based on two key criteria: how fast can they charge, and how well they communicate with charging stations and the electric grid. The North American model (J1772) offers easy home and business charging, but is limited by its bulk and speed (it converts electricity from the domestic alternating current (AC) to direct current (DC)). A combined version known as CCS1 allows DC fast-charging. In Europe, a CCS2 standard combines DC and AC charging in one plug, but has some voltage and power limitations. Nissan and Mitsubishi’s Chademo standard works well with the electrical grid, but is concentrated in Japan. Tesla has combined the best of the models in one: It’s small, lightweight, and capable of fast-charging, yet remains proprietary (though adapters exist).

At stake in the plug war is wider acceptance of EVs and the future of the grid, says Sioshansi. Mass adoption of electric vehicles will require drivers to be confident they can refuel without gambling on finding the right plug (although a little planning avoids this). The 20% of charging that happens at work or on the road is infrequent but essential.

If enough drivers make the switch, EVs can become a more robust part of the electric grid. Utilities are investing billions of dollars to turn EVs into networks of distributed batteries that balance the power supply, enabled by two-way communication built into future chargers: They’ll talk to the vehicle to maximize battery life by managing the flow of electricity. When intermittent renewables like wind and solar power more and more of the grid, this will be critical.

Consolidation is coming, but for now the diverse standards will help drive EV adoption, as long as the industry eventually cooperates. “We have to remember that the lack of standards in the beginning of an innovation journey is a good thing,” says Giovanni Bertolino of Enel X. “It actually drives innovation.” He points to the world wide web’s evolution from a tangle of communication protocols to an Ethernet standard now supported by billions of global devices.

Governments are already forcing the issue. The EU is pushing manufacturers to adopt its preferred CCS2 standard. It’s working. In Europe, Tesla has retrofitted its Supercharging stations with the ports, and installed them on new Model 3s sold in the bloc. Similarly, Nissan’s Ariya SUV has left the Chademo world for the CCS2 standard. “I believe there will eventually be one new legislated standard for EV charging,” says Greenlot’s Holland, noting Europe has already passed laws to standardize charging cords for mobile phones.

In the US, Bill Loewenthal, a product lead for EV charging network ChargePoint, says the writing is on the wall for a common standard. The company’s 114,000 charging stations around the globe already offer compatible plugs for a given region. But the CCS1 standard is gaining market share in the US, and Tesla is offering adapters or even adopting common standards (as it has in the EU).

Soon, he argues, refueling with electricity won’t seem all that different than picking the octane at a gasoline pump.