Don’t give up on your buff just yet

Neck gaiters, buffs—whatever you call them, the jersey-type loops of fabric that can be worn around the neck and over the face and nose—have been a favorite of athletes during the Covid-19 pandemic. Unlike masks, which can fall off the ears, outdoor runners and cyclists enjoy the ease of pulling buffs up as they pass the occasional dog-walker or fellow jogger, and then down again once they’re alone.

Neck gaiters, buffs—whatever you call them, the jersey-type loops of fabric that can be worn around the neck and over the face and nose—have been a favorite of athletes during the Covid-19 pandemic. Unlike masks, which can fall off the ears, outdoor runners and cyclists enjoy the ease of pulling buffs up as they pass the occasional dog-walker or fellow jogger, and then down again once they’re alone.

Recently, though, major headlines have called the efficacy of neck gaiters into question. Stories in the Washington Post and CNN stated that buffs may actually transmit more droplets than wearing no mask at all.

These stories are reporting research from scientists at Duke University and a local health group called Cover Durham based in North Carolina. The work, published on Friday, Aug. 7 in the journal Science Advances, tested 14 different types of masks, including buffs. It found that neck gaiters made out of a polyester spandex material allowed more droplets of liquid to pass through when the wearer was speaking than any other type of face covering—and even bare lips.

The results sound alarming and even counterintuitive after months of hearing that cloth face coverings can provide some protection for others during the pandemic. But the truth is, this study was never intended to study the efficacy of buffs and other face masks at all; it was more about designing a new way to test mask efficacy. And without comparing this new droplet-measuring method to existing methods, it shouldn’t be used to completely rule out buffs as a face covering.

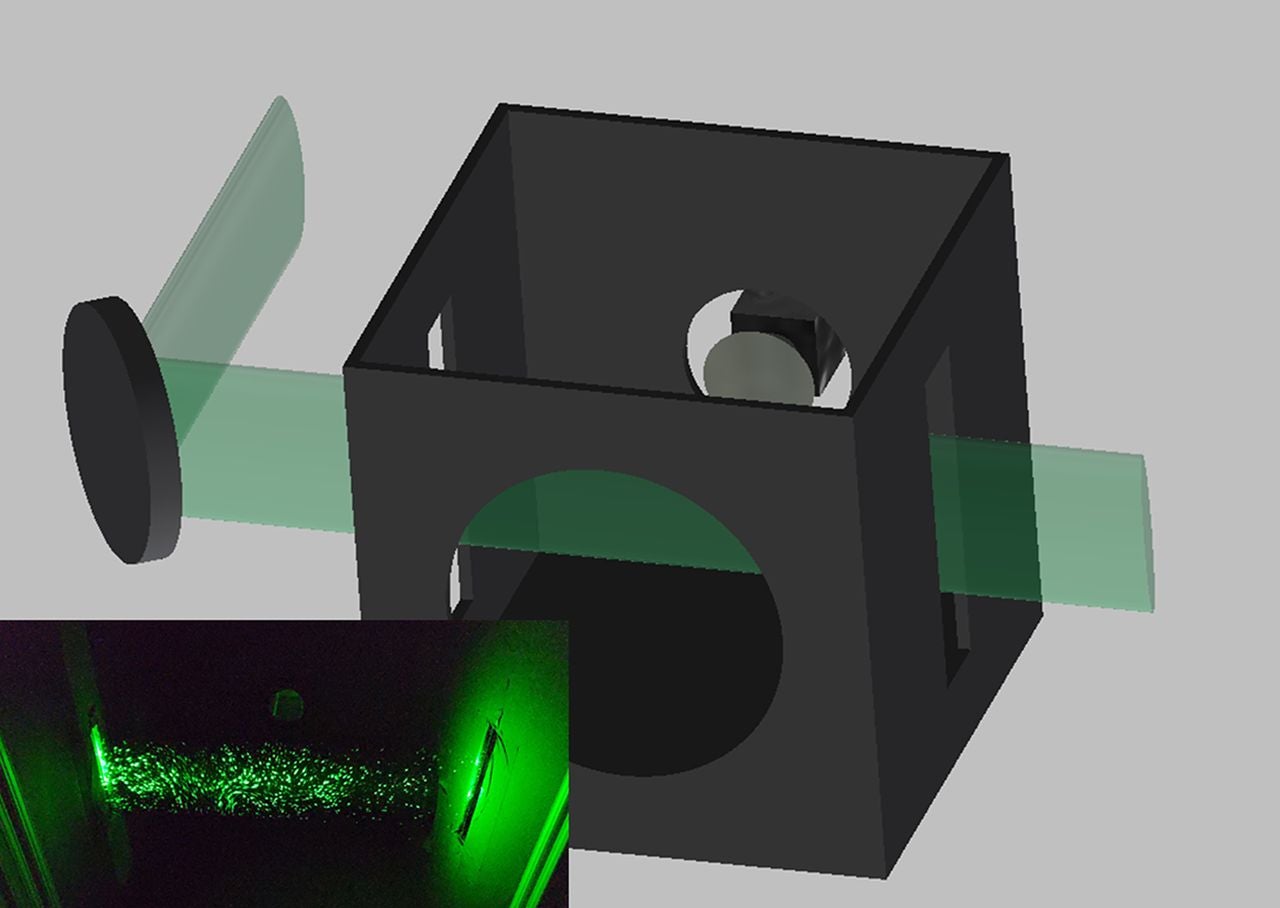

The team from Duke created a simple system using lasers to create a measure of mask efficacy. First, they beamed a laser through a slit in the side of a box, creating a sheet of light. Through another hole in the box, a person spoke while wearing different types of masks; any droplets that made it through would scatter the sheet of light, which a cell phone camera at the other end of box could then capture. The contraption looked like this:

The paper was meant to be a proof-of-concept for this new method of testing masks, as Popular Science reports. Currently, groups like the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and the European Union have their own standards for testing face masks, says Christopher Zangmeister, a researcher who studies aerosols at the US National Institutes of Standards and Technology.

Using these standards to measure mask efficacy is tricky. They generally involve sending air with tiny particles of sodium chloride through a mask, and then measuring how much sodium chloride winds up within the mask, Zangmeister says, but the process requires precise measurements that have to be done in a well-equipped lab. N95 masks, which are used in medical contexts, have all been tested to meet these standards.

“We have not compared our method to other measurement techniques,” Martin Fischer, a chemist and physicist at Duke who led the work, told Quartz in an email. So although the team’s method could be a cheaper, easier approach, it hasn’t been tested sufficiently yet. And it certainly was never intended to rank different kinds of masks, he told Wired.

The dataset generated from the study is small, and the study does not try to explain how a stretchy buff could generate more light refraction from particles than no mask at all. NIST’s Zangmeister notes that this could make sense if the fabric of the buff was actually breaking up the larger droplets we exhale into smaller ones. “You can imagine that you have this big particle, it hits a fiber and it explodes and you make lots of small particles,” he says. But in all his time working in aerosols, he’s never seen that happen.

Instead, it’s better to take these kinds of studies as you would with all coronavirus news: in the context of all the data scientists have amassed so far. Other major public health organizations, like the World Health Organization, have looked at all the existing data on mask efficacy. While no study reaches exactly the same conclusion, generally, they agree: Triple-layer cloth masks that have some kind of filtration layer and water-repelling properties can protect others from your nose and mouth droplets, and, to a certain extent, you from other people’s droplets. Neck gaiters, while they tend to be just a single layer thick, could protect some droplets from escaping below your mouth, as Abraar Karan, a physician at Harvard Medical School, told NPR.

In short, it’s too soon to throw out your buffs. If you’re a concerned athlete, however, you can make sure to layer your buff over your nose and mouth, or you can go back to a more traditional cloth mask. Sure, it’s a little less convenient, but it could give you peace of mind.