Moving back in with your parents may be your worst fear—and your best idea yet

Once, when I was struggling with a big life decision some years ago, my therapist asked me a question: What was the worst possible outcome I could envision?

Once, when I was struggling with a big life decision some years ago, my therapist asked me a question: What was the worst possible outcome I could envision?

My answer was instant: “Moving back in with my parents.”

It was nothing personal: I love my parents, and I was lucky I could count on them to take me in if I needed them. But I hadn’t lived at home since I was 16. Like a lot of modern-day, middle-class Americans, I’d absorbed the idea that moving back in with your parents was a sign of failure, something people had to do when they lost their jobs or went through a breakup or otherwise found themselves in crisis. No adult who had a viable alternative would choose to live at home.

Or so I thought, until the Covid-19 pandemic sent me and many other adults scurrying back to our parents’ homes, with the impetus ranging from newfound unemployment to health concerns, desperately needed help with childcare, and, in my case, the desire to have the comfort of family and companionship during a crisis—not to mention access to a backyard.

In the US, 35% of people in their 20s lived with their parents or grandparents as of June 2020, up from 30% before the pandemic. While the share of people in their 30s living with parents hasn’t changed since Covid-19 arrived, anecdotal reports suggest there are plenty of people across age groups who are merging households with their parents, whether temporarily or indefinitely.

The circumstances behind these living arrangements are far from ideal. But for the first time, I’ve realized something that people from other countries and cultural backgrounds have long known: Living with your parents isn’t necessarily a place of last resort. It’s an opportunity to grow closer and support one another. Perhaps most surprising of all, it can even be … fun.

Living at home during the pandemic

I fled to my parents’ home in suburban Ohio in mid-March, propelled by a strong desire not to spend the weeks ahead quarantined alone with my dog in Brooklyn in a junior one-bedroom. I didn’t know how long I’d be staying, exactly, but I had my mail forwarded until June. As it turned out, that was a good guess—I was there for almost three months.

“Why aren’t we fighting more?” I mused to friends over Zoom one evening early on in quarantine, befuddled by the ease with which my parents and I had settled into a routine. On weekdays, we each retreated to separate corners of the house to work, waving briefly at each other on periodic trips to the refrigerator. Around 6 pm, my mom and I would walk the dogs—mine and theirs—around the neighborhood. My father and I switched off making dinner, and I experimented with new recipes: ricotta gnocchi with sage and peas, coconut green curry, a soup called Roberto.

Afterward, we would watch old movies like The Long Goodbye or The Lady Vanishes, or peel off again for various telephone calls and Zoom dates. On the weekends, my mom and I went for hikes, working our way through local nature reserves we’d never carved out time to visit before. My dad stayed home to write or grade papers, providing detailed updates about the creatures he spotted at the bird feeder by the kitchen window.

Outside the house in suburban Ohio, there was still disease and economic turmoil and suffering. My company had layoffs. My dad lost one of his two jobs. My mom stressed over the switch to remote work. And we had all the standard family squabbles. My dad insisted on rearranging the dishwasher every time I loaded it; I was constantly begging him to put the cable news channel on mute.

But compared to when I’d lived at home as a teenager, things were bizarrely peaceful. We understood each other better now, and knew how to ask for, and give, space when we needed it. And mostly, I was just grateful to be with my family during the scariest period of my lifetime.

The benefits of multigenerational living

For much of US history, adult children living with their parents was the norm. As journalist Claudia Kolker explains in her book The Immigrant Advantage, when most Americans lived and worked on farms, it was simply practical to have the whole family together under one roof.

In the 19th century, however, romantic marriage took priority over the larger extended family—a trend exacerbated by the rise of Sigmund Freud and his tell me about your mother ilk. “Psychiatric theory began to portray the traditional family as a vat of psychological turmoil,” Kolker explains. Between the 1920s and the 1960s, health experts advised young adults to strike out on their own, and the economic boom of the post-World War II era meant that doing so was within reach for many, particularly for white Americans.

As a 2011 report from Pew Research Center points out, multigenerational living has remained a crucial economic safety net for groups that often have limited financial resources, including young adults, Black people, Hispanic people, immigrants, and the unemployed. Expanded household sizes are “an important adaptation to economic crises and the limitations of the welfare state,” says sociologist Katherine Newman, author of The Accordion Family and Falling from Grace, a book about downward economic mobility.

Extended family living may be born of practical necessity, but it also creates a self-reinforcing sense of devotion, as Newman found in her research. When middle-class families face unemployment or housing crises, she says, “their support networks are very fragile … They don’t have the ties of reciprocal sharing that are very common among poor families.”

In this sense, as David Brooks observes in a recent essay for The Atlantic, the fact that American policies and institutions treat the nuclear family structure as the default is yet another way of entrenching inequality. “We’ve moved from big, interconnected, and extended families, which helped protect the most vulnerable people in society from the shocks of life, to smaller, detached nuclear families (a married couple and their children), which give the most privileged people in society room to maximize their talents and expand their options,” he writes.

During recessions, the rigidity of the nuclear family ideology loosens; everyone understands why young adults move back home with their parents. But when the economy is stable, many middle-class and upper-class Americans perceive a stigma attached to the figure of the adult child who lives at home, particularly once they’re out of their mid-20s.

Implicit in this stigma is the all-American idea that the goal of parenting is to raise a child who becomes autonomous, and that independence is better than interdependence. It’s one thing to have a young adult living at home to save on expenses while they get a degree or take a low-paying internship. “But if Johnny’s in the basement playing video games, that’s a different story,” says Newman. “In the US, we have a culture of self-reliance and a conviction that individual responsibility is really key. And very often we’ll forget that these big structural waves of change are not really entirely in the control of individuals.” Perhaps Johnny is in the basement playing video games at age 30 not because he’s a lazy good-for-nothing, but because he owes $100,000 in student-loan debt.

Or perhaps Johnny just likes living with his parents—and what’s so terrible about that? In some countries and cultures, the function of the family isn’t so much to prepare children for lives of self-reliance as to persist as a long-term force for mutual aid.

In Italy, for example, the attitude is “of course the children are at home, they’re always at home until they marry,” Newman explains. “What’s changed is the age at which people marry.” (The average Italian woman and man get married at about 32 and 35 years old, respectively, compared to an average 26 and 29 years old in 1990.)

Kolker’s research on West Indian families in the US, meanwhile, found that these communities tend to perceive multigenerational living as a practical step toward ensuring a family’s long-term success, making higher education and homeownership more attainable and providing high-quality childcare for young kids. In addition, Kolker says, “there are a lot of emotional and social benefits to having a lot of people around. In a lot of cultures besides Anglo-American culture, it’s just considered more pleasant.”

This is not to suggest that the US is an aberration in the global community. In Japan, the rise in adult children staying at home was “received as a moral catastrophe—a collapse of the society’s ability to produce adults,” Newman says. The trend was perceived as an indictment of absentee fathers, who were said to have been so busy working that they had effectively abandoned their families, hobbling their children’s ability to mature. Unmarried adult children who remained at home are sometimes known by the unflattering term “parasite singles.”

And in Nordic countries like Sweden and Denmark, Newman says that multigenerational households are not so much stigmatized as altogether unusual. The robust welfare state offers much of the economic support that the extended family might otherwise provide.

There are a lot of benefits to living in countries that offer free college, universal healthcare, generous unemployment benefits, and state-subsidized childcare and eldercare. But for all the upsides, Newman was surprised to find that many of the Nordic people she interviewed felt rather disconnected and lonely.

“They would say, We don’t really love each other as much as other cultures. We’re too isolated from one another; we don’t need each other as much,” she explains. Newman realized that families are closer when they need each other. “Economic dependence creates these bonds.”

Recognizing our parents’ humanity

For some Americans, the pandemic has served as a reminder of just how much we need our families. My former Quartz colleague Hope Corrigan, who is 27, spent five months living with her mother in Florida this year.

She hadn’t planned on this arrangement. Corrigan and her boyfriend left New York City to go to an out-of-state wedding the second weekend of March, just as the gravity of the pandemic was sinking in, and never went back. Her boyfriend went to his parents’ in Louisiana, and Corrigan, with only a weekend’s worth of clothes, joined her mom, three cats, a rescue dog named Argyle, and a feral cat colony living in the backyard of their house in Pensacola.

“I just wanted to be there with her because I didn’t want her to be by herself for that time. With everyone going into lockdown, it’s taxing on mental health,” Corrigan says. “So I ended up just staying, and it was the best decision.”

Even while paying rent on her New York apartment, she saved money easily. She and her mother divided up chores and took turns cooking. At night, when Corrigan was through with work, they watched TV together and went on walks; on weekends, they’d head to the beach and go paddleboarding or biking. It was the first time she had lived with her mom since high school. “Having her as an equal was so much fun,” she says. “I was like, ‘Okay, my mom is a human.’” She eventually returned to New York City, but says she’d happily live with her mom again. “When I came back up here, I was very sad to leave her,” she says.

The experience made Corrigan realize how grateful she is to have the option of moving back home. It’s one thing to know in the abstract that you have family as a safety net, and another to test it out and find that it holds up. It also changed her opinion about what it means to live with your parents as an adult.

“I always felt like people who moved back in with their parents in their 20s were failures, because that’s what society has conditioned us to think,” she says. “Then I did it, and I was like, Wow, this is really fun, and I’m saving so much money. Now I know why other cultures do it. You live with your parents and they live with their parents; that bond is much stronger when you do.”

Extended family as safety net

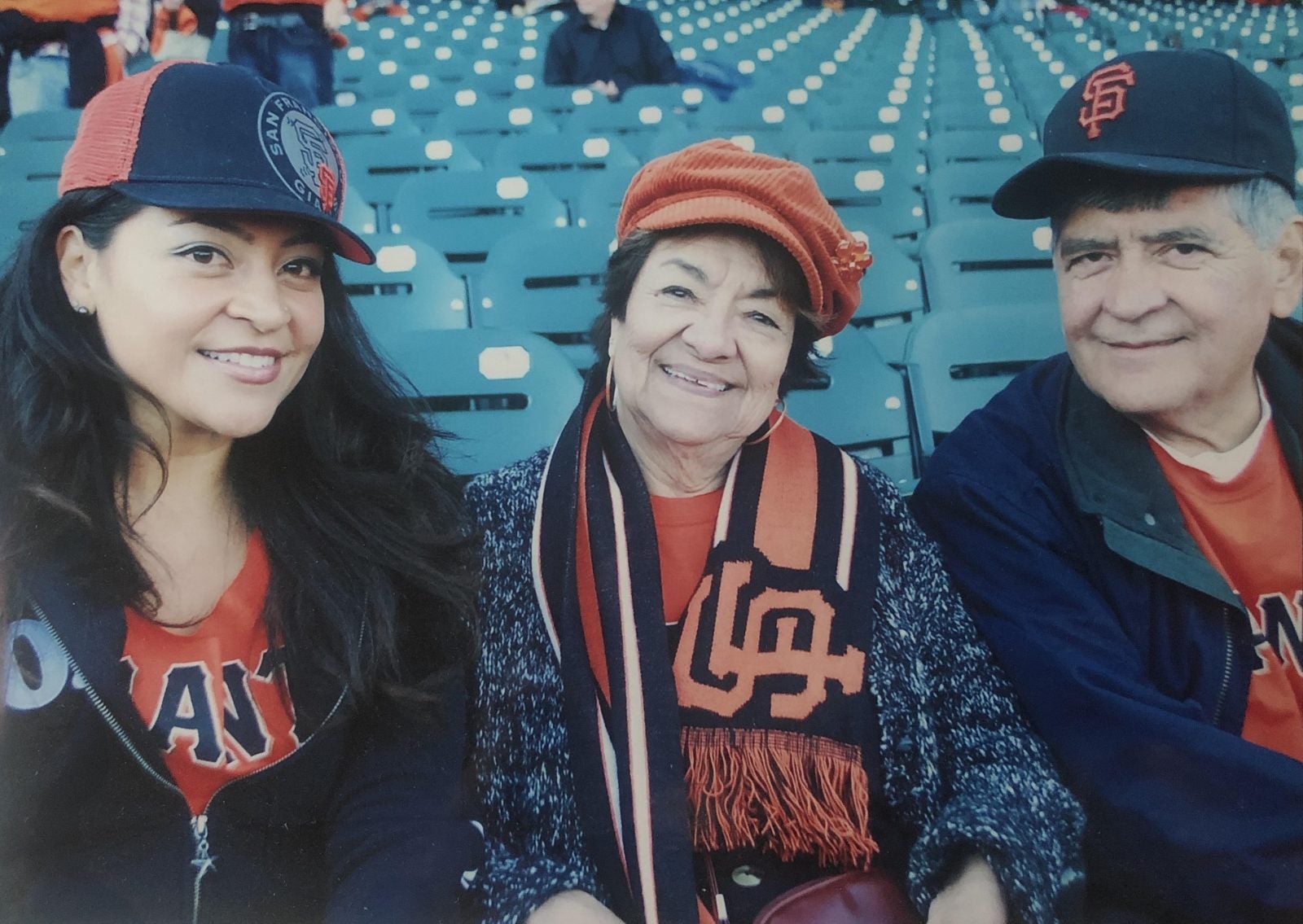

Perlita Dicochea had been practicing multigenerational living well before the pandemic hit. Dicochea, who works in communications at Stanford University, first moved back in with her parents in her 30s in the midst of a career transition away from academia. Eventually, she moved out and started a family of her own. But when her relationship ended, Dicochea moved in with her parents again, accompanied this time by her two young children.

In Latino culture, Dicochea notes, multigenerational families are more common—but “there’s not one simple pattern.” In her middle-class family, it was “assumed that we grow up and move on, or definitely if you have kids, you’re with your husband.”

It took a while for both her and her parents to accept that her path had diverged from that norm, she says. “We went through a hard time, and I had to face a lot of childhood issues.”

But now she thinks the nuclear family isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. “I see my friends who are married and living in nuclear families, they both need to work, they’re raising these kids, it’s really tough,” Dicochea says. She’s grateful for the ways her family functions as a collective unit—from the benefits her children derive from spending time with their grandparents every day to the flexibility she has to dash out for an errand.

Dicochea also says she’s lucky the house is big enough to give everyone some space. Her parents’ bedroom is at one end of the house, and they tend to spend the bulk of their time in the living room and dining room. She and her children share a bedroom at the other end of the hall, and use a third room as the kids’ playroom; they also have a kitchenette.

She’s aware that many families aren’t as lucky. “There needs to be more support for multigenerational living,” she says. “It needs to be easier for people to add a room or add a granny unit, or whatever challenges there might be in having spaces that facilitate multigenerational living.”

Dicochea doesn’t gloss over the challenges of living with her parents: “If I had the economic means, my initial decision would be for me and the kids to live on our own,” she says. But at the same time, she says, “If I was able to leave tomorrow, my parents would be devastated.” And she knows she would miss them, too. “Even now, if my parents are out two or three hours, I don’t like it,” she says. “I’m like, This is weird.”

The rebirth of closeness

Of course, extended family living can create plenty of problems. For one thing, there’s a big difference between a situation like mine in Ohio (three people in a three-bedroom house) and a lot of people crammed into a one-bedroom apartment. “I don’t want to minimize the fact that if you’ve got a household that starts off in a strained economic situation where interpersonal conflict erupts out of that strain, it can lead to very serious problems behind the curtain,” Newman says.

The lack of privacy that comes with having multiple generations under one roof can also drive people mad. Kolker interviewed a Jamaican social worker living with her parents for The Immigrant Advantage, and found that the best strategy was to set up healthy boundaries.

“The closer the quarters, the more formal one becomes, and the more you respect those emotional walls,” Kolker says.

Susan Newman, a social psychologist and the author of Under One Roof Again, says the importance of boundaries applies equally to parents and adult children. Parents need to avoid nagging their 29-year-old children about cleaning their rooms or lecturing them about their career choices, and adult children have to take care to avoid transforming back into their teenage selves, expecting their parents to cook all their meals and slamming doors shut in frustration.

“Treat your parents with the respect and care and caution that you do with your friends,” says Newman. Set ground rules about who’s responsible for which household chores, hone in on common interests, and approach conflicts with a sense of “mutual support and trust, and forgiveness if a friend does a bad thing to you.”

Multigenerational living arrangements don’t have to involve regressing back into childhood; instead, they can be an opportunity to build a new kind of relationship. Katherine Newman observes that, under the right conditions, extended-family living “can lead to rebirth of closeness.”

I was thinking about life cycles and new eras on my mother’s birthday in late May. In a wild burst of overconfidence in my baking abilities, she’d requested a French tea from Simone Beck’s cookbook, including a multi-layer shortbread cake filled with coffee, orange, mocha, and chocolate buttercreams, which Beck appropriately calls Le Formidable. Meanwhile, my father had spent the day assembling my mom’s birthday present, a new teal-colored adult tricycle (she’d never quite mastered the bike). After dinner, we all went outside and cheered as she wobbled down the street.

“Don’t film this,” my mom said as she pedaled by.

“I won’t,” I promised, filming.

Later that night, I wondered how many of my coupled friends who were also in their 30s were weathering the pandemic with their partners and children. It would have been easy to compare myself to them, and to slip into feeling bad about what showing up at my parents’ house solo implied about my progress—or lack thereof—toward the traditional milestones of adulthood.

Yet I didn’t feel bad about it. Back when I had imagined moving in with my parents as a worst-case scenario, I’d been projecting not just about the loss of independence it might represent, but the shame and sadness I might feel if I didn’t have a partner to turn to instead. It was the stigma of loneliness, just as much as the stigma of failure, that made moving home seem like a terrible fate. But that was only how I thought when looking at myself through a critic’s eyes.

Coming home showed me there’s no need to pour my sense of self-worth into whether I fulfill the whole self-sufficient nuclear dream. I hope to have a partner and kids. But whatever happens, I want to keep cultivating the kind of kinship where everyone depends on one other—parents and grandparents and grandkids, siblings and cousins, and chosen family and beyond, a diagram with arrows flying in every direction. And I want to remember that, when my worst-case scenario finally came to pass, I wasn’t focused on the life I didn’t have, but grateful for the love I did.

Charts by Dan Kopf.