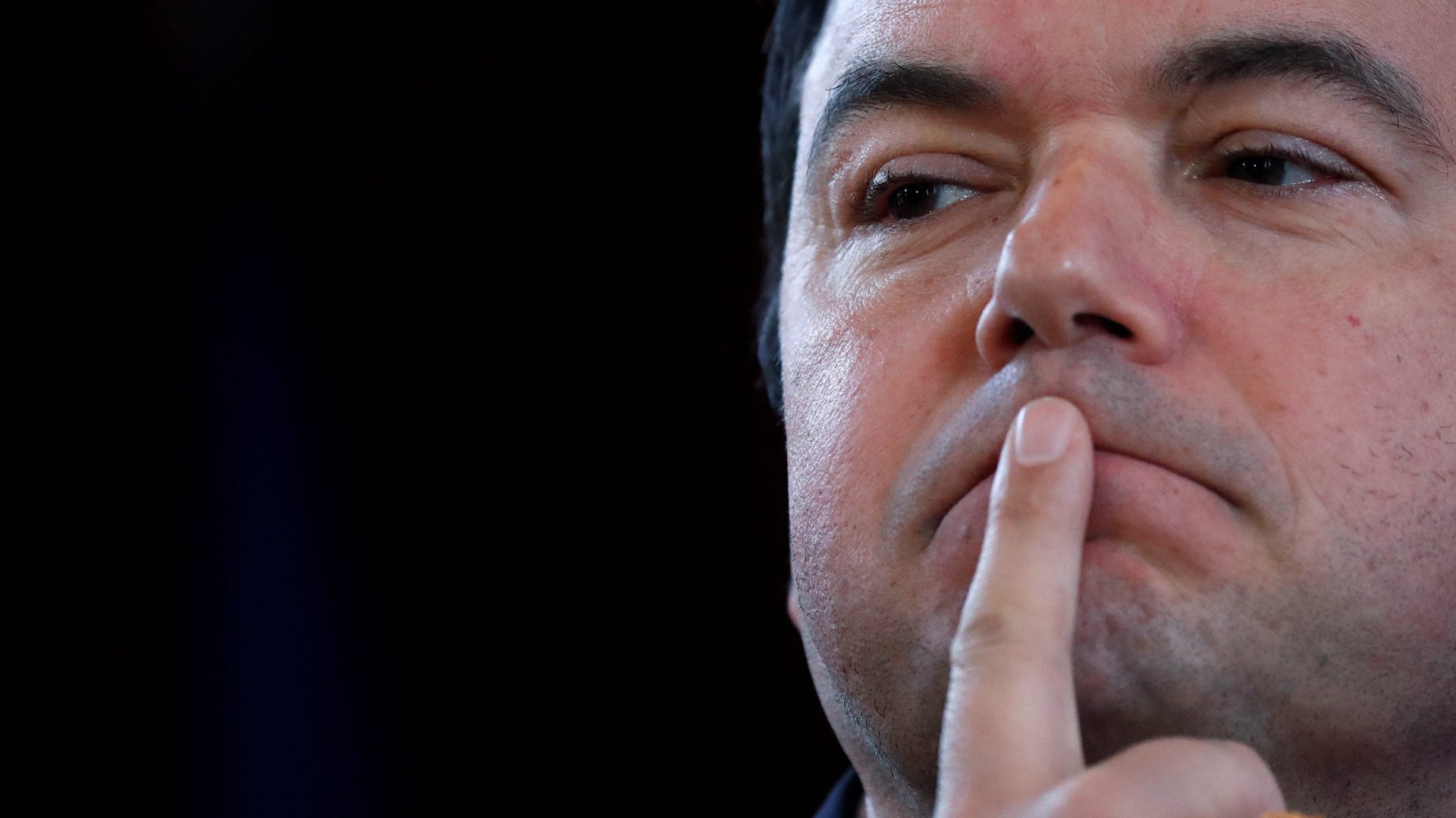

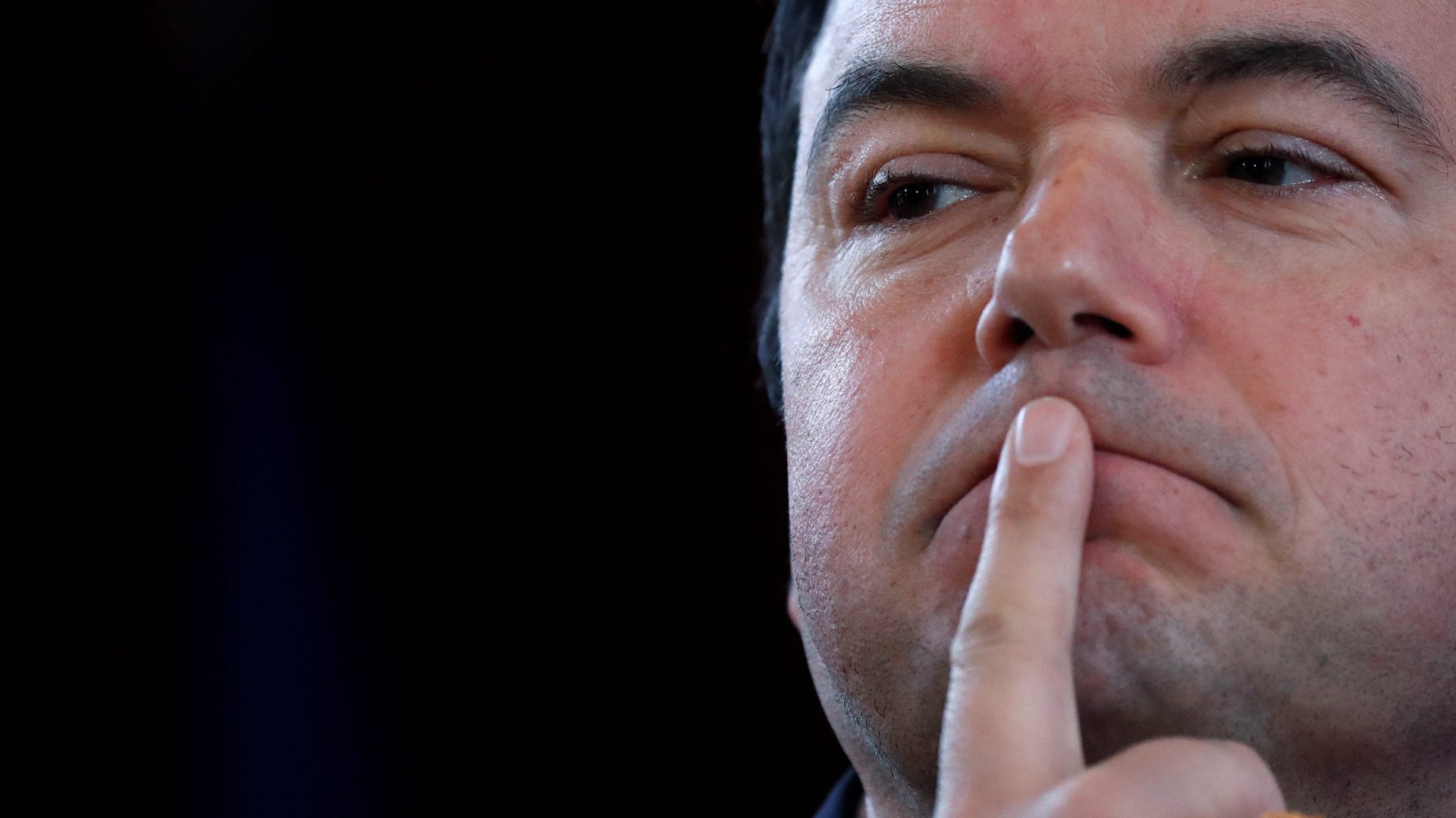

Beijing loved Thomas Piketty’s critique of capitalism—until he turned to China

Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century was a big hit in China, as 700-page tomes on economic theory go. A few years after its publication, the French economist’s 2013 book got a shout-out (link in Chinese) from president Xi Jinping, who praised Piketty’s use of statistical evidence to showcase Western countries’ historic levels of inequality.

Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century was a big hit in China, as 700-page tomes on economic theory go. A few years after its publication, the French economist’s 2013 book got a shout-out (link in Chinese) from president Xi Jinping, who praised Piketty’s use of statistical evidence to showcase Western countries’ historic levels of inequality.

Piketty’s audacious follow-up, Capital and Ideology, is getting a much frostier reception. Published last year, the new book widens its scope to focus on inequality in places like India, Brazil, Russia, and China. Beijing did not appreciate the scrutiny. According to the South China Morning Post, Piketty’s Chinese publisher, Citic Press Group, has demanded that all sections related to inequality in China be cut. “I refused these conditions, so at this stage it looks as if Capital and Ideology won’t be published in China,” Piketty told the SCMP.

The topic of inequality may be all the more sensitive these days as China recovers from the pandemic, which has disproportionately hit (paywall) its poor migrant workers and will likely widen the income gap between urban and rural populations.

In a tweet, Piketty said that it was “sad that [Chinese leader] Xi Jinping’s ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ shrinks itself from open discussion.”

In the book, Piketty draws on research he co-authored and published last year, and which uses tax data, surveys, and China’s national accounting statistics to estimate the growth of Chinese inequality from 1978 to 2015. He found that the share of the country’s income held by the top 10% of China’s population rose from 27% in the late 1970s to 41% by 2015, comparable to the levels of inequality seen in the US.

The book also criticizes the lack of detailed data on Chinese income tax, making it impossible to get a fully accurate picture of how the country’s gains in wealth have been distributed over the years. While a 2006 government order required high-income earners to file special declarations, the data was rudimentary and publication ceased in 2011. Piketty was able to scrape together regional data in subsequent years, but they were “irregular,” “inconsistent,” and “fragmentary.”

The criticism doesn’t stop there. If good income data is hard to come by, Piketty wrote, it’s even worse with data on wealth. There is no inheritance tax in China, and therefore no data on inheritances, making it exceedingly difficult to study wealth concentration. “It is truly paradoxical that a country led by a communist party, which proclaims its adherence to ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics,’ could make such a choice,” Piketty wrote.

It also means that China is, by one measure, the world’s best place to be a billionaire. As Piketty explains: ”So we find ourselves in the early twenty-first century in a highly paradoxical situation: an Asian billionaire who would like to pass on his fortune without paying any inheritance tax should move to Communist China.”

Which books China decides to censor, and which it allows on shelves, is full of contradictions, and censorship itself is a constantly shifting line. George Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm have been available for decades, though at least one school has removed the novels as part of a recent nationwide book-cleansing drive. Last year, China censored parts of Edward Snowden’s autobiography, but the former US intelligence employee found a way to get around the censors: posting the censored tracts on Twitter and crowdsourcing translations.