Closing schools for Covid-19 hurts students’ financial future

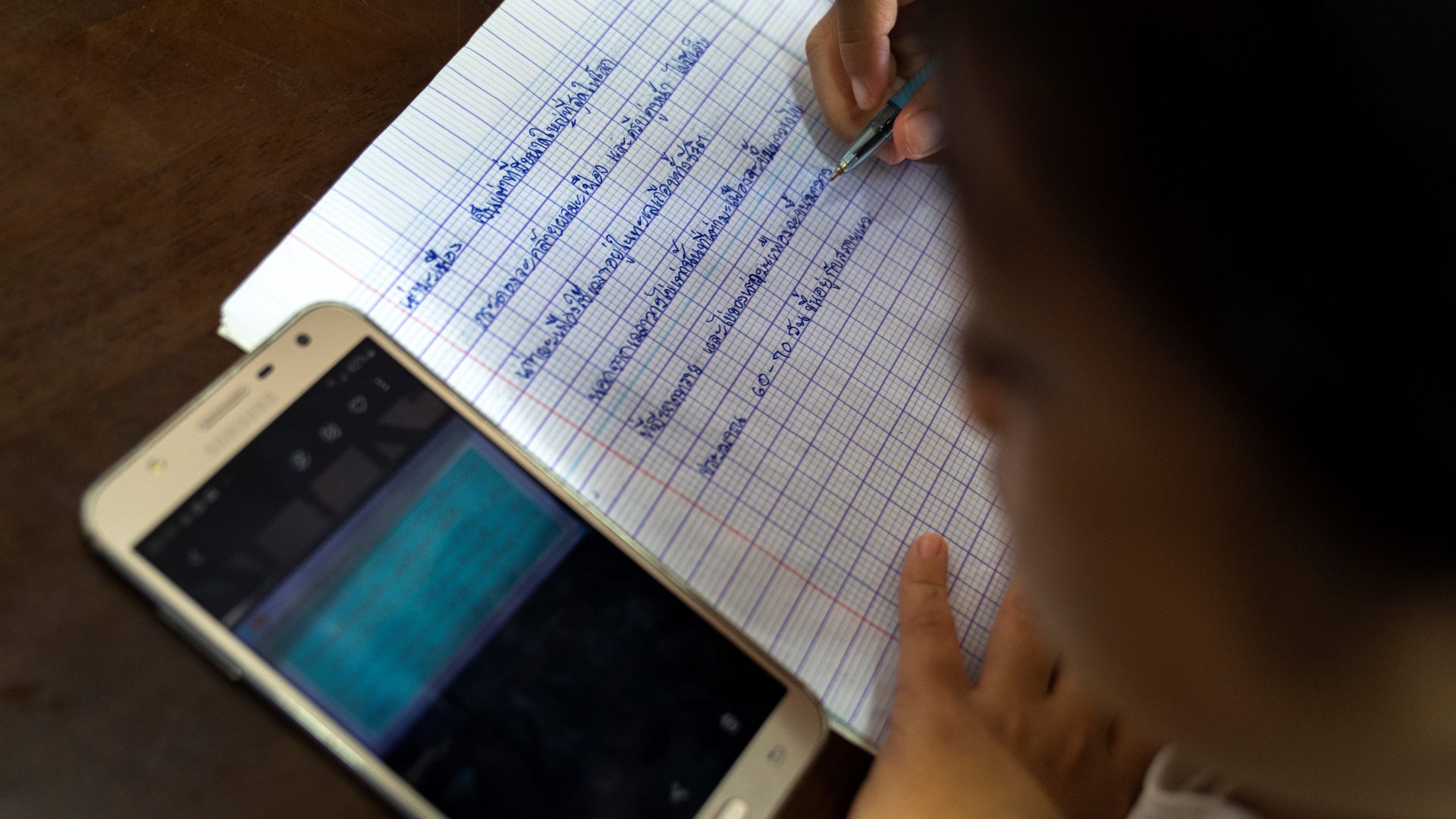

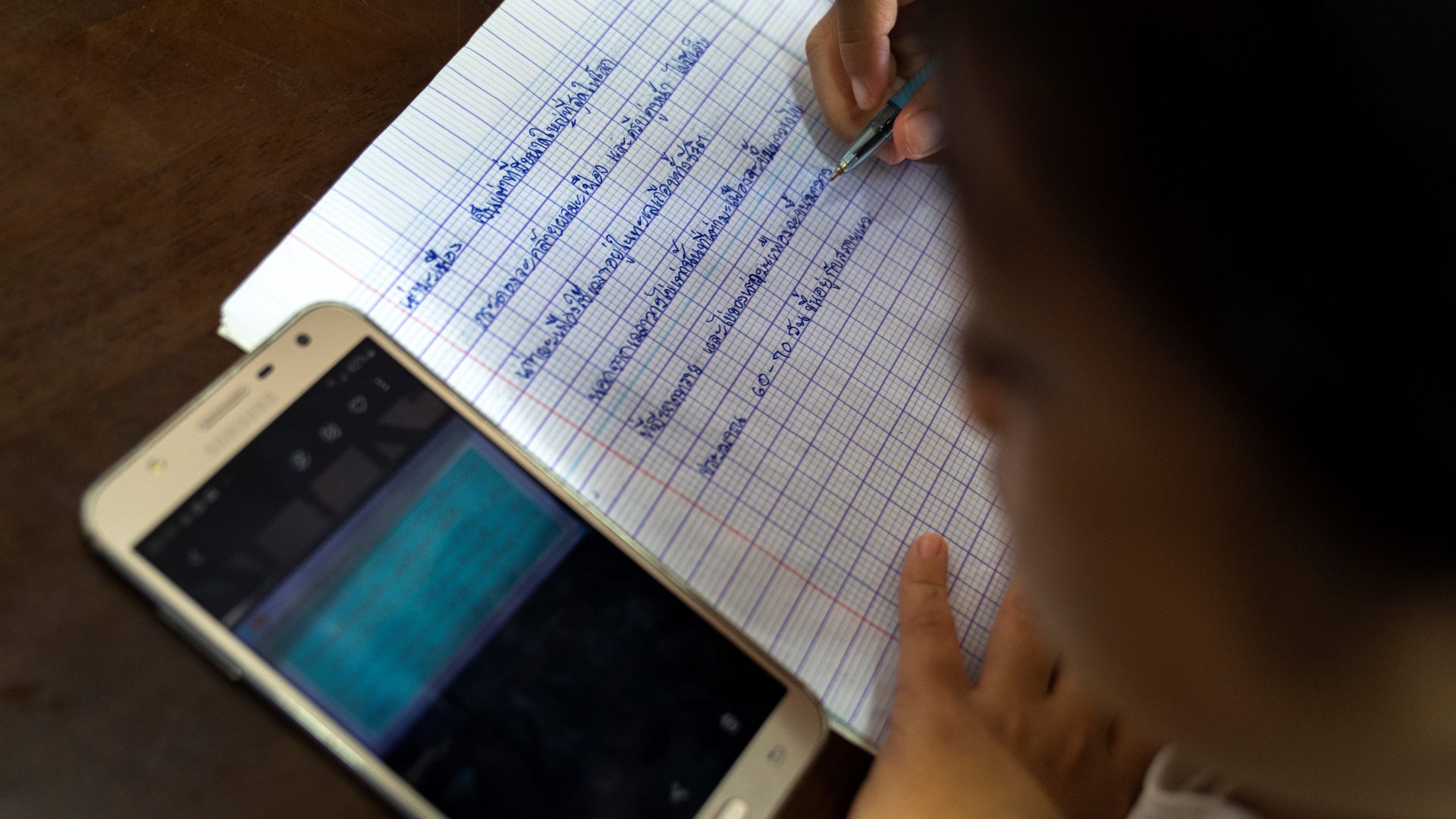

As schools worldwide have sent students home to protect against the spread of Covid-19, the impacts of the time spent out of the classroom have begun to come into focus. During the first half of 2020, many students have fallen behind academically as they’ve relied on remote learning, which will make it harder for many to meet grade level expectations. Some might see a loss of the skills they’ve already developed.

As schools worldwide have sent students home to protect against the spread of Covid-19, the impacts of the time spent out of the classroom have begun to come into focus. During the first half of 2020, many students have fallen behind academically as they’ve relied on remote learning, which will make it harder for many to meet grade level expectations. Some might see a loss of the skills they’ve already developed.

Now, researchers are even getting a sense of what those losses might mean for students’ economic prospects into adulthood, according to a new OECD report (pdf). The researchers found that most students will see approximately 3% lower earnings in their careers—likely more for disadvantaged students, broadly defined as students from low-income or low-education households, according to Eric Hanushek, an economist at Stanford University and one of the authors of the report.

The learning losses students have already felt, which may be exacerbated by reopening strategies, “will follow students into the labor market, and both students and their nations are likely to feel the adverse economic outcomes,” the report reads.

The longer schools stay closed, the greater the potential losses, especially for children in countries where greater cognitive skills, and more years of schooling, lead to higher earnings.

Other researchers have estimated economic losses similar to the OECD’s 3% projection; one report from June approximated 2-2.5% loss on earnings in the US, while another from July estimated about 3% for students in the UK.

As a result, nations’ GDPs are also expected to suffer. “For nations, the impact could optimistically be 1.5% lower GDP throughout the remainder of the century and proportionately even lower if education systems are slow to return to prior levels of performance,” according to the OECD report.

The report’s conclusions are based on a wealth of literature linking learning—metrics include years of schooling and test scores—to future income opportunities.

To minimize these losses, the authors of the report recommend improving teacher efficacy—”for example, ensuring that the teachers who are best able to use video and internet instruction have more students, while those best at in-person instruction should concentrate on that,” Hanushek says—as well as providing more individualized instruction to help students catch up.

It will take a long time to see the full economic impact of this period, Hanushek says, though we can have a sense of how kids are doing in the meantime via standardized test scores. He’s also concerned that schools will emerge worse, and not better, once the coronavirus crisis is in the past.

“The thing that people seem to underestimate is the importance of learning,” says Hanushek. “They often seem to assume that just getting a certificate of graduation is what counts—not realizing that a high school diploma can signify very different levels of learning.”