In a facial recognition bill backed by Microsoft, three words stand between citizens and their civil rights

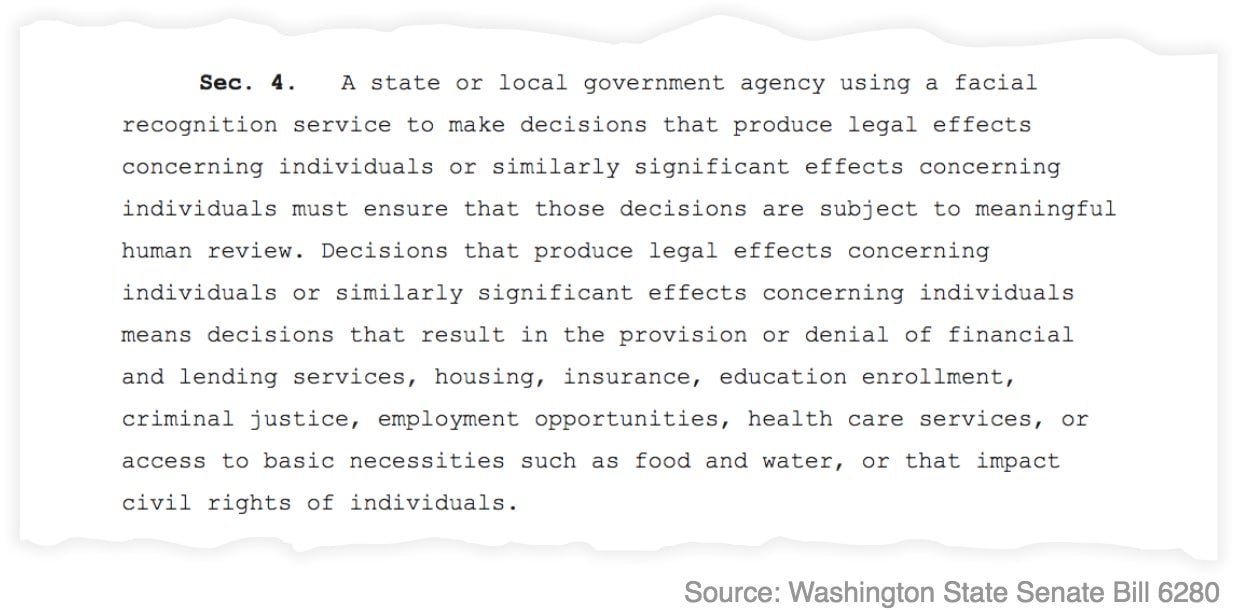

In Washington, the first US state to pass a law regulating facial recognition, it’s legal for government agencies to use facial recognition to deny citizens access to basic rights and services—under one condition. The AI-powered systems must be subject to “meaningful human review.”

In Washington, the first US state to pass a law regulating facial recognition, it’s legal for government agencies to use facial recognition to deny citizens access to basic rights and services—under one condition. The AI-powered systems must be subject to “meaningful human review.”

Under the law’s definitions, so long as a trained human being has power to overturn the machines’ decisions, governments can use facial recognition systems to deny people access to loans, housing, insurance, education, jobs, healthcare, food, water, or their civil rights. The law leaves private companies’ use of facial recognition unregulated.

Washington’s law was written by a Microsoft employee and passed with strong lobbying support from the Seattle-based software giant. And now, those three words are spawning copies: After state legislators introduced the bill in January 2020, lawmakers in California, Maryland, Idaho, and South Dakota took up similar bills. They have nearly identical language about human review—again under lobbying pressure from Microsoft.

In the absence of federal regulation on facial recognition, state and local governments have begun to fill in the gap with a patchwork of their own laws. Tech companies, led by Microsoft, have dispatched lobbyists to state capitals across the country to support loose regulations on facial recognition instead of bans that would squash the development and sale of the technology.

“The fact that a lot of these bills look like each other and match what the tech companies are calling for is just evidence of their influence,” said Jameson Spivack, a policy associate at Georgetown University’s Center on Privacy and Technology. “By getting out ahead of calls for bans or moratoria or stricter regulations, it allows them to steer the conversation better.”

Civil liberties watchdogs worry that looser regulations, which allow companies to keep their facial recognition businesses intact, will leave citizens with fewer protections. When Washington’s bill passed in March, the local ACLU chapter pilloried the “meaningful human review” clause, which it said is not a sufficient safeguard against the misuse of facial recognition.

“People routinely succumb to automation bias, deferring to output from computer decision-support systems, rather than using their own judgment,” ACLU Washington technology lead Jennifer Lee argued in a blog post. “‘Meaningful human review’ is a deeply flawed concept and should not be used to justify use of face surveillance technology to make critical decisions.”

Academics who study AI ethics have been calling for human oversight of AI systems for years. But Maria De-Arteaga, an assistant professor at UT Austin who studies the role human reviewers play in AI decision-making systems, says the mere presence of a person isn’t a panacea.

“Thinking about human oversight is very important, but by itself it doesn’t provide you any guarantees,” she said. Factors like how much time people have to review an algorithm’s work and the type of training they get play a big role in how good they are at catching machines’ mistakes, she explained.

The Washington law—and the mirror bills in California, Maryland, Idaho, and South Dakota—contain identical, imprecise language that leaves a lot up to interpretation. The bills simply say that human reviewers must “have the authority to alter the decision under review” and be trained periodically on how facial recognition systems work and how to interpret their decisions.

“It doesn’t really change that much about how facial recognition is used, especially when the language is as vague as it is in this law,” Spivack said. He added that the regulations would be more useful if they specified that human reviewers follow, for example, a set of guidelines based on the Facial Identification Scientific Working Group’s standards for image comparison and training.

But De-Arteaga says the human review requirement falls short on a more fundamental level. “Adding a human doesn’t address the fact that facial images are an unjustified basis for decision making in a vast number of cases,” she said.

The ACLU argues that the main problem with the Microsoft-backed bill is that, in exchange for weak restrictions, it enshrines in law the legality of using facial recognition for making critical decisions about people’s lives: “Alternative regulations supported by big tech companies and opposed by impacted communities do not provide adequate protections—in fact, they threaten to legitimize the infrastructural expansion of powerful face surveillance technology.”