Turkey’s prime minister is finding it hard to put Twitter back in the bottle

Hours after Turkey’s prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan promised to “eradicate” Twitter in order to demonstrate the “the power of the Turkish Republic” on March 20, the ban went into effect. Users signing in from Turkey saw a message from the country’s telecom regulator that the site was blocked for their “protection.”

Hours after Turkey’s prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan promised to “eradicate” Twitter in order to demonstrate the “the power of the Turkish Republic” on March 20, the ban went into effect. Users signing in from Turkey saw a message from the country’s telecom regulator that the site was blocked for their “protection.”

But, then, a curious thing happened. Twitter in Turkey didn’t fade to black. In fact, many users in Turkey are still tweeting away, at the reported rate of 17,000 tweets a minute. There’s been little disruption to the service, this journalist for the Hurriyet Daily News claims:

In fact, the block itself quickly became the most-discussed topic…on Twitter in Turkey:

Even some of the Prime Minister’s allies seemed to take the ban less-than-seriously….which they conveyed in messages on Twitter:

International activists and Twitter personalities chimed in with messages of support, like this Egyptian Twitter personality with over 50,000 followers:

And famous foreigners offered help, again on Twitter, though these offers earned some derision. (After all, if you’re blocked from Twitter, how would you see the message?):

Right now, Erdogan, is grappling with a fact that may confound politicians for years to come—Twitter and other social networks, once unleashed on a population, are difficult to stamp out. Erdogan’s ban comes after Twitter and other social media were used to circulate voice recordings, allegedly of him and his son, discussing business bribes and other indications of corruption and poor governance. Last summer, dozens were detained in Turkey for “inciting riots” after tweeting in support of anti-government protests in Gezi Park.

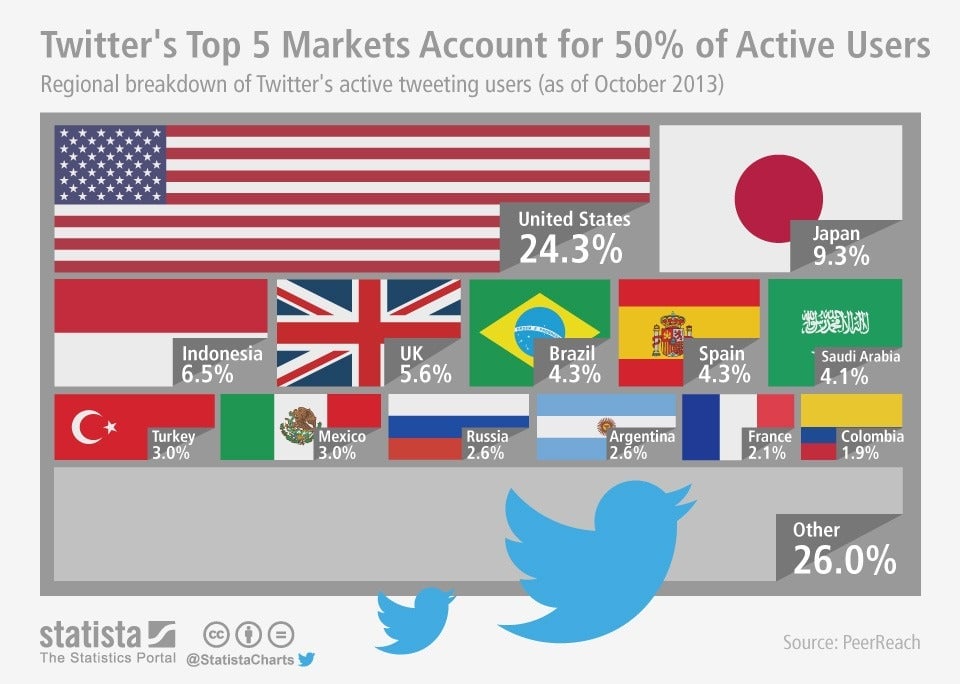

The detentions seem to have done little to deter citizens from using Twitter. As of October, 2013, Turkey was one of the social network’s top ten markets, according to data from Peer Reach, which analyzes Twitter use.

Turkey’s internet-savvy, youthful population (the median age is 29) has proven adept at getting around the recent block, using VPNs that mask their internet address so they appear to be coming from another country, along with other work-arounds such as an SMS option offered by Twitter itself.

Turkey’s citizens also relied on traditional ways of spreading information, albeit to point to ways to get back into the social media stream, painting Google’s Domain Name System address (which helps internet users evade country-wide blocking schemes) on posters of ruling party leaders:

Censorship of social media sites like Twitter and YouTube has been successful in China, but that’s mostly because they were never popular there. Once users reach a critical latch on a social network, as Turkey has with Twitter, it’s much harder to clamp down.