What quarantine foods you should buy if you hate cooking

I eat to stay alive. Sure, I like the idea of cooking, and I love a good home-cooked meal (I do the dishes in return). But I’ve never had any interest in cooking for myself.

I eat to stay alive. Sure, I like the idea of cooking, and I love a good home-cooked meal (I do the dishes in return). But I’ve never had any interest in cooking for myself.

Before the pandemic, this was fine: For breakfasts, I’d stick to eggs with spinach and cheese and toasts; for lunches, I’d bring a sandwich, leftovers, or frozen meal into the office. For dinner, my partner and I would either grab a bite to eat, or he’d cook and I’d clean. On nights when we weren’t together, I’d make something small for myself—usually involving the microwave.

I could get away with this routine because I am in my late 20s, am privileged to have no dietary restrictions, and am a parent only to some plants and a cat. Once Covid-19 hit, however, my affinity for cooking became yet another pressure point for 2020: As much as my partner likes cooking, he understandably didn’t want to do it all the time. Going out was no longer an option; single frozen meals feel a lot sadder when you’re eating them every day. And as much as I’d like, it’s impossible to subside on snacks alone. I’d have to learn how to cook.

I am not alone in my aversion to the kitchen. A 2017 survey by food analyst Eddie Yoon found that only about 10% of people in the US actually love cooking. About half of them hate it—despite the fact that it may feel like an unpopular opinion. Yet fear not, fellow culinary-phobes: There are groceries you can buy to support your quarantine cooking that don’t make you want to stab your eye with a fork.

For me, the biggest barrier to learning how to cook was identifying why I don’t like it. Once I figured out those aversions, I started to figure out how to adjust my meals to avoid them—not just surviving, but actually enjoying my food.

The problem: Not enough time (or patience)

The solution: Stir fry it, or prep it and leave it.

I am very good at planning a lot of things in my life, but very bad at planning others. Like being hungry: When I am not hungry, I do not want to stop what I am doing to think about what I may want to eat when I am hungry. When I am hungry, I merely want to end the physical sensation as soon as possible so I can get on with my day.

This strategy to eating means that you miss out on variety very quickly. There are only so many sandwiches and snacks you can make.

I’ve found that for me, the solutions are either quickly stir-frying vegetables that can’t be undercooked—peppers and tomatoes (technically fruits)—or roasting others that can’t be overcooked, like brussels sprouts, cauliflower, broccoli, beets, and squash (okay, you could overcook them, but I love a little crispy crunch). Both of these tactics take no more than 10 to 15 minutes of total prep. Roasting does technically take longer to come to fruition, but there’s no boredom involved; you can simply leave it in the oven for your 20 or 40 minutes while you go back to doing things you actually enjoy.

The problem: Even supposedly easy foods turn out flavorless

The solution: Spices, herbs, and oils.

One of the mistakes I made in the early days of the pandemic was thinking that I only needed the basics like salt and pepper to cook. And while that’s true, it gets very boring very quickly—tricking you into thinking you can’t cook.

A spice cabinet with variety is key. This way, even if you cook the same kinds of foods over and over again (like chicken thighs), you can change up the meal even more by experimenting with seasoning. If a whole bottle seems like too much of an investment, take a look at the international aisle, where smaller portions of some spices may be available in bags.

There is no right set of spices to have on hand. Over time, my household has amassed a collection of oils, salty spices like onion, garlic powder, and umami mix, and different kinds of heat, like chipotle and a shichimi togarashi mix. We also keep herbs like turmeric, parsley, bay leaves, and saffron. For more inspiration, you can check out these food bloggers and see which strike your fancy.

The problem: No interest in minutia

The solution: Find a small thing that piques your interest, and lean into that.

I’ve found that experienced cooks love to talk about the details of their recipes and specific ingredients—how swapping out one type of salt for another can change the texture of a dish, or how different kinds of peppers bring unique heats. If that excites you, lean into that feeling!

But it’s okay if talk of bread yeast variety makes your eyes glaze over. (It does for me.) The wonderful thing about food is its incredible diversity. No matter what level of cooking you do, there is a food niche for you—and most require simple ingredients you’d find at your normal grocery store.

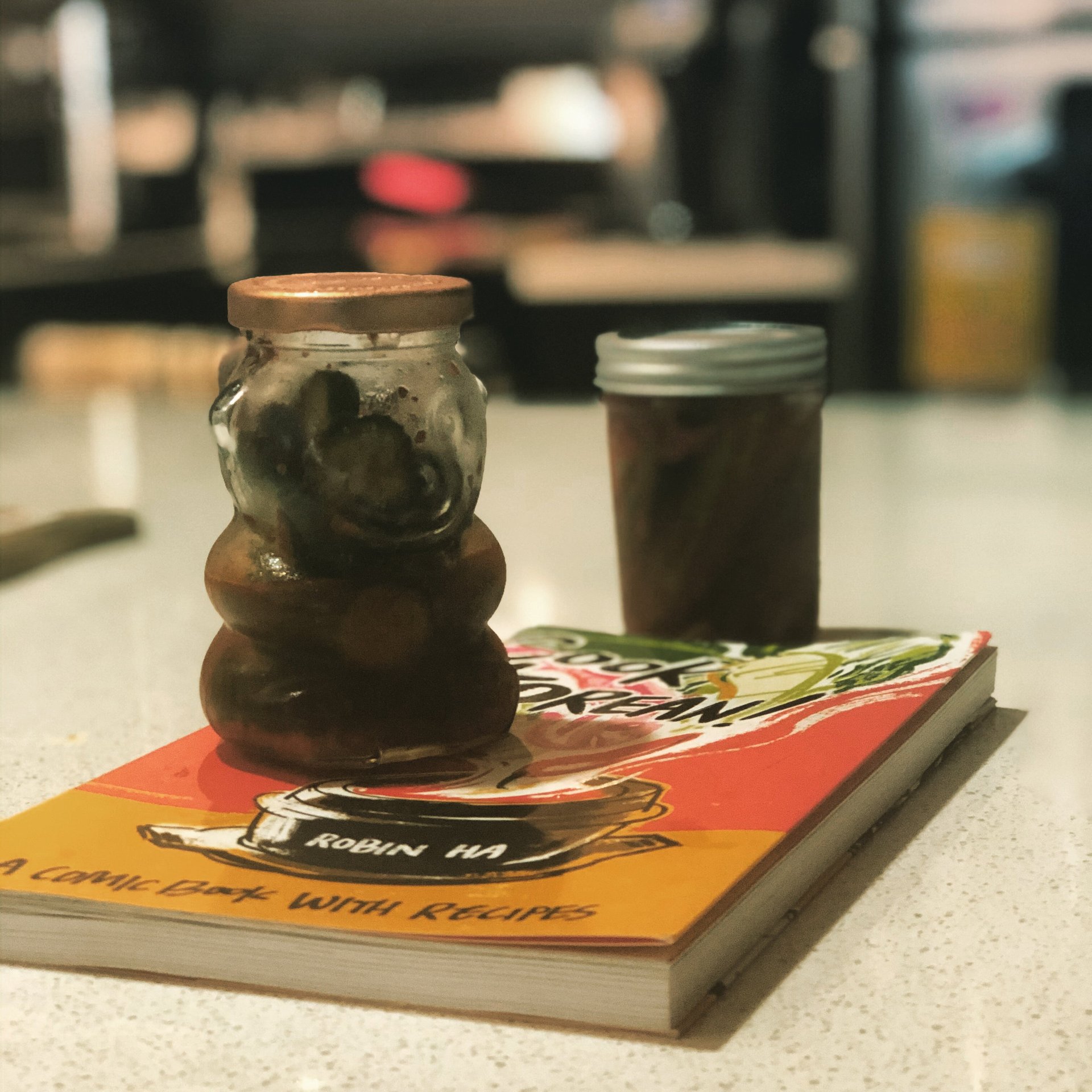

For example, while I am not particularly interested in food aside from its nutritional value, I am interested in bacteria. And I love the tang of vinegar and salt—particularly as a rehydration drink after a run. So I started looking into pickling. I cracked open Robin Ha’s Cook Korean!— a comic cookbook that teaches readers about making traditional Korean foo I bought at a local art fair—and then started adapting Ha’s pickling recipes to other kinds of vegetables. You don’t have to buy a book, though—there are all kinds of recipes for pickles online.

As of May, I now pickle cucumbers, okra, onions, radishes, and even avocado for snacks for my future self. Ha’s book was a starting point for me to experiment; once I learned the very basics of pickling—which can only take about 15 minutes for the simplest of recipes—I realized I can experiment and play around with the fuel I feed my little Lactobacillus bacteria to get different kinds of fermented flavors.

And, okay, it’s not cooking when I make side dishes that force bacteria to do most of the work, but it still forces me to think about food and its flavors in a way I wouldn’t ordinarily. It’s a start.

You, too, can find these little niches in the world of cooking that work for you! It may take a little trial and error, but once you identify the framework that piques your interest, you’ll find there’s much more to explore.