These companies are mining the world’s data by selling street lights and farm drones

Few tech bigwigs get excited about disrupting nitty-gritty municipal markets like street lighting. Even fewer have ever set foot on an actual farm, much less thought of technology designed for one. But the boring world of basic needs and utilities hides huge opportunity for tech’s favourite revenue source: data.

Few tech bigwigs get excited about disrupting nitty-gritty municipal markets like street lighting. Even fewer have ever set foot on an actual farm, much less thought of technology designed for one. But the boring world of basic needs and utilities hides huge opportunity for tech’s favourite revenue source: data.

At first glance, it’s easy to think that Sensity Systems simply sells light fixtures. But the lights are just a means to an end. Sensity’s real interest lies in data gathered from sensors it embeds in fixtures for new LED (light-emitting diode) bulbs. “Today we’re selling lights because we have to demonstrate to customers that this works,” says Hugh Martin, Sensity’s CEO. “But over time we don’t have to be in the lighting business.”

Sensity is one of several companies that have grown up around the idea of densely networked “smart cities” embedded with sensors. At last count, 143 cities around the world had some sort of smart city project (pdf) underway. Silver Spring Networks, another light-sensor firm, is networking 20,000 streetlights in Copenhagen. AGT, a Swiss security firm, is working with Cisco to install internet-connected sensors in trash bins in an Asian city. Some 100 recycling bins in London are already hooked up to the internet.

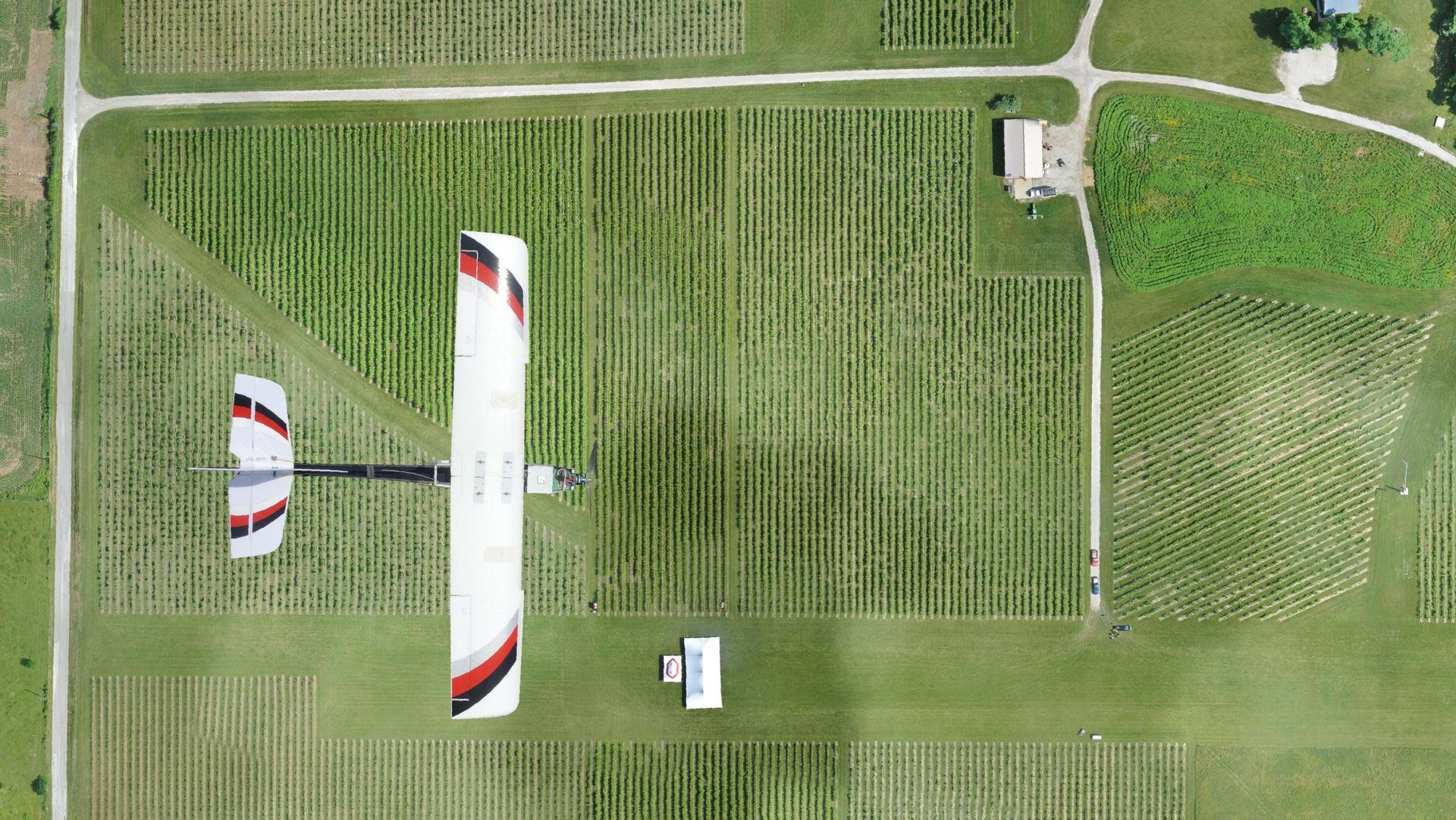

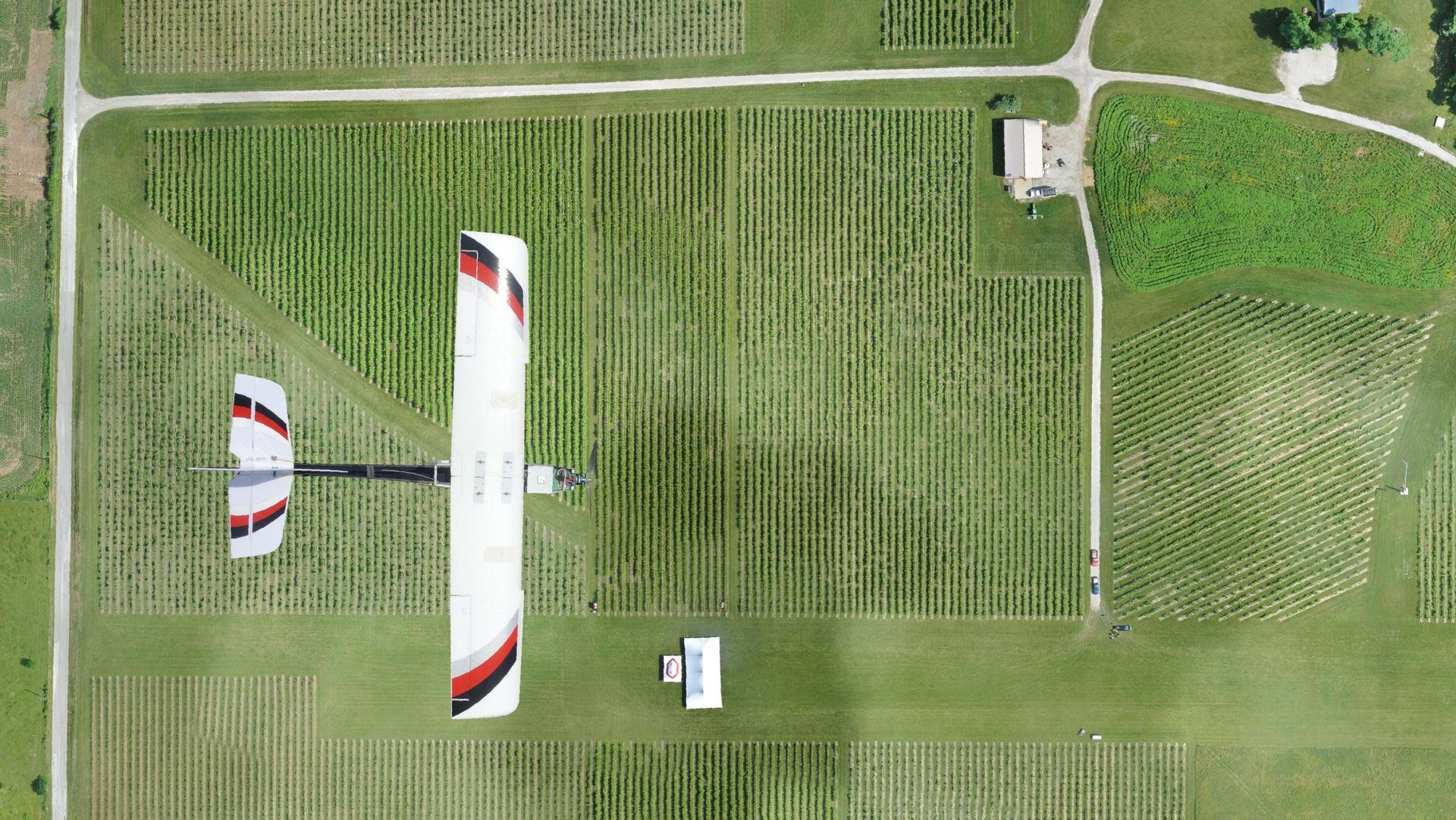

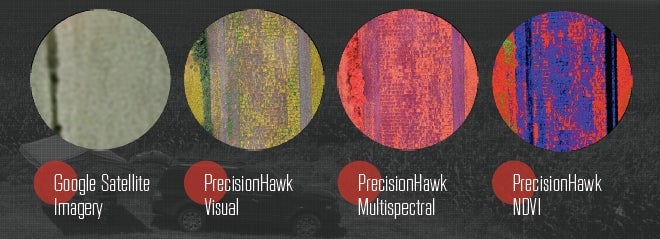

It’s not just urban centers. Farmers see a great deal of value in data from sensors too. PrecisionHawk, a company based in the United States and Canada, hopes to grow big selling drones laden with sensors to large agricultural firms. Again, though, PrecisionHawk isn’t in the drones business; it’s in the data business. “The airplane itself is a convenient means to the end to get them that data,” says Ernest Earon, PrecisionHawk’s president. He sees a future where “the hardware just comes with part of the subscription, with the software service.”

Sensors everywhere

The potential of sensor networks is hard to overstate. Take parking lots. With Sensity’s fixtures, sensors that sit around the lights can figure out where a parking spot is and whether there’s a car in it. If the parking lot is indoors and has a relatively low ceiling, a single sensor could track maybe six spots. A high street light outdoors could see 12 to 15 spots. By contrast, a system being installed in London right now involves bashing a sensor into the ground under each parking spot.

Depending on what kinds of sensors the light’s owners choose to install, Sensity’s fixtures can track everything from how much power the lights themselves are consuming to movement under the post, ambient light, and temperature. More sophisticated sensors can measure pollution levels, radiation, and particulate matter (for air quality levels). The fixtures can also support sound or video recording. Bring these lights onto city streets and you could isolate the precise location of a gunshot within seconds.

You could also track individuals using their mobile phones (something the City of London recently learned does not sit well with everyday people). Martin sees a world in which people could walk right into a stadium without a ticket because sensors in the lights overhead would communicate with fans’ phones, which would remain in their pockets. And “if it’s your birthday, they’ll offer you a hot dog,” he says.

In agriculture, drones with sensors can help farmers answer their questions with ease. Have the seeds sprouted? Do we need to go out and replant? What is the biomass of a field? What does the middle of my cornfield—invisible behind eight-foot-high corn stalks—look like? PrecisionHawk promises that chucking an unmanned aircraft in the air will provide farmers with the data they need quickly and efficiently.

Seeing the light

Sensity marks itself out from other networking firms by taking advantage of a huge change that is underway: Martin reckons that there are some 4 billion outdoor or overhead light fixtures that, in the coming decades, will switch from using power-hungry incandescent or sodium bulbs to energy-efficient LEDs. These consume only a fifth as much as energy but last up to 25 times as long. They also use the same low-wattage power supply common in electronics. Sensity’s idea is to convince businesses, cities and local councils that if they’re upgrading their lighting, they may as well install Sensity’s sensor-capable fixtures for a small extra cost.

But like PrecisionHawk, Sensity sees greater value in the data it collects than simply piping it back to the client whose gadgets generated the data. Sensity’s clients own their data just like they own their lights and the land on which those lights stand. Yet land is finite, and there are only so many lightbulbs that you can sell, while data can be sliced up in millions of ways to serve different purposes.

Sensity figures it can license the data from its owners to sell it to third parties, developing a a service “that has nothing to do with the guy who provides the lights,” Martin says. This data could be sold to people interested in tracking earthquakes, global warming, and a range of other things. Martin says the model is for Sensity to charge third-party users to access this data. It will share revenues with the data owners.

PrecisionHawk is less clear about who exactly owns the data collected by its drones. ”That is something we’re working on to try and find a model that works best,” says Earon. While existing customers own their data, Earon suggests that future clients may be asked to opt into sharing. He argues that the specifics of a field interest only its owners. But in aggregate, data from around a county, country, or the world could be useful for other farmers, for central planners, and for policymakers. Indeed, aggregating the data could even help the farmers themselves, if it means lower premiums for crop insurance.

The internet of streetlights

Both companies have seen some early successes. Though a deal to light up all of El Salvador with its sensors fell through, Sensity is making progress with private enterprises, such as malls, where a single contract could mean a big order. The Westfield Valley Fair mall in Santa Clara, California installed Sensity’s system in its parking lots and is considering expanding it to other locations.

PrecisionHawk’s Earon says he counts many of the world’s biggest seed firms as his clients, though he declined to name them. The company must wait for the US Federal Aviation Administration to allow drones over America’s skies (for which it won’t even develop rules until next year) before his business can take off on home turf. Meanwhile, PrecisionHawk is targeting customers in Canada, where the company started life catering to vineyards, and outside North America. There’s plenty of business to go around: Gartner forecasts there will some 26 billion sensor-enabled things in the world, excluding phones, tablets, and computers, by 2020.