Covid-19 is a case study in how universal basic income can fix hunger

Starting in 2017, a group of economists at MIT and other universities set out to study the impact of universal basic income. In rural Kenya, they identified about 10,000 poor households to receive no-strings-attached cash payments—some as a lump sum of $500, others with that amount spread out over two years, and still others who would receive the equivalent of 75 cents per person per day for 12 years. Another 4,000 households would go without the extra help.

Starting in 2017, a group of economists at MIT and other universities set out to study the impact of universal basic income. In rural Kenya, they identified about 10,000 poor households to receive no-strings-attached cash payments—some as a lump sum of $500, others with that amount spread out over two years, and still others who would receive the equivalent of 75 cents per person per day for 12 years. Another 4,000 households would go without the extra help.

Universal basic income (UBI) is popular in theory among some economists and policymakers as a means to confront poverty. But it has been tested in the real world only a few times, and many questions remain about how to make it work. One the researchers were keen to investigate was the degree to which the payments could help Kenyan families weather an unanticipated economic crisis. Normally, this is impossible to test—you can’t just flip a switch to destabilize the economy.

In this case, they didn’t have to. In the midst of the experiment, the coronavirus pandemic swept the globe—and in September, the researchers reported that the cash transfers proved decisively effective. People who received cash payments were up to 11% less likely to report experiencing hunger (defined here as missing at least one meal in a day) than the regional average, and up to 6% less likely to report an illness.

On the surface, this result shouldn’t be surprising: Of course giving impoverished people money during a crisis will help them afford the basics. And yet, in many countries, the stigma against NGOs or the government handing out cash as a means to confront problems like hunger and illness has proven remarkably resilient. What if people stop working? What if they blow the money on booze or other indulgences?

Apart from being classist and racist, those assumptions are being blown apart by empirical evidence collected during the pandemic. The Kenya study was only the latest example.

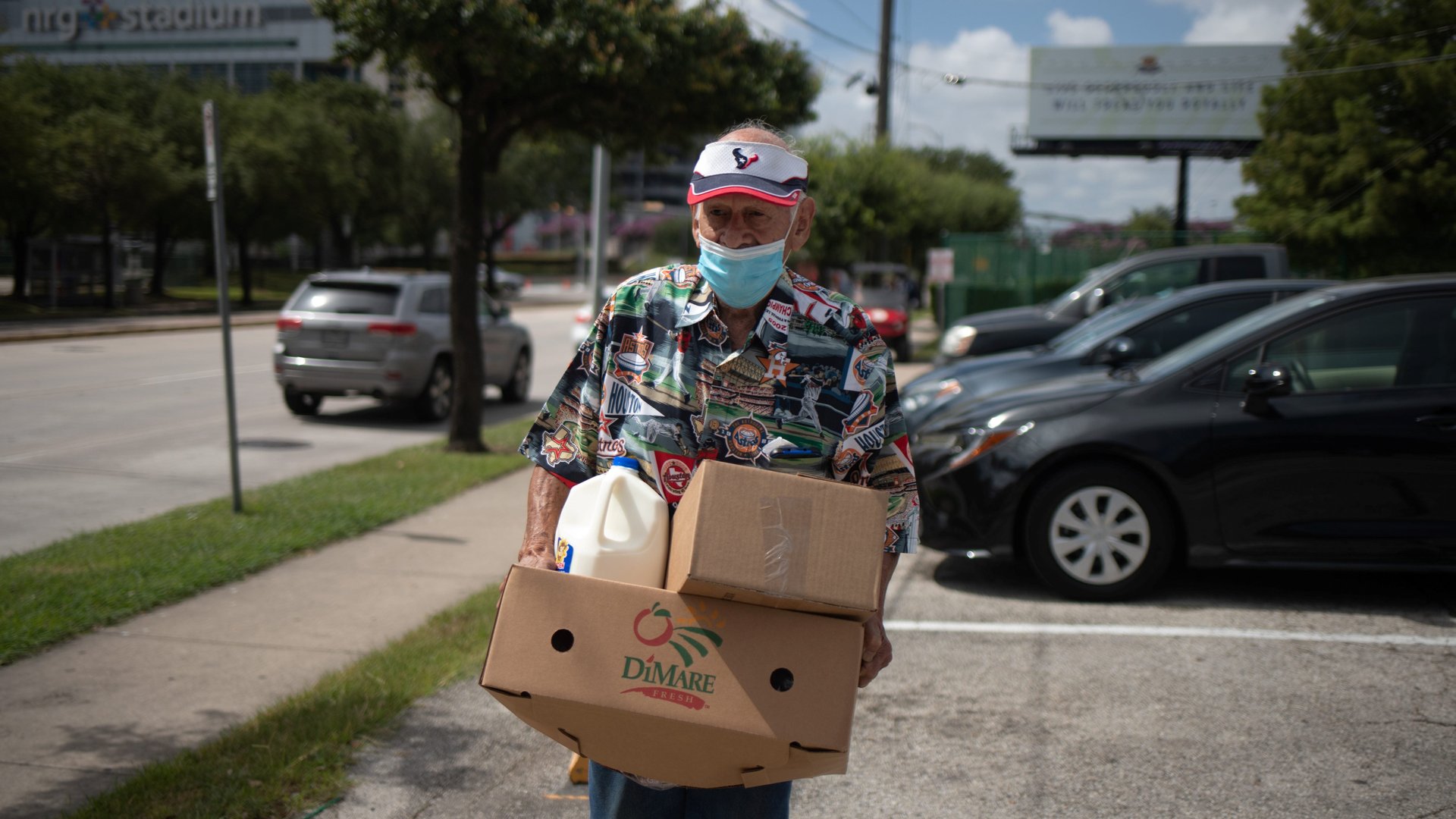

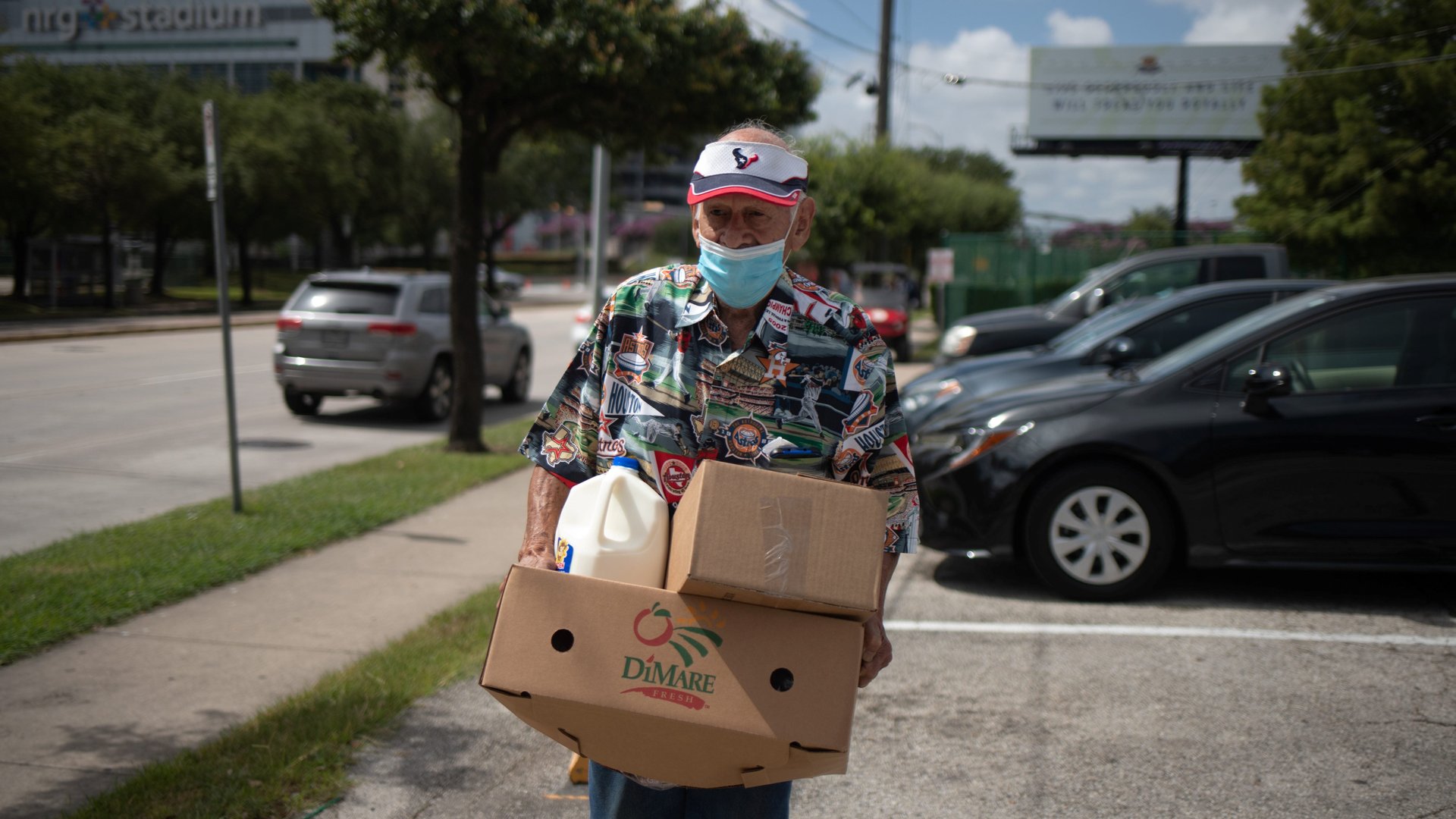

New data on the power of cash transfers may help to permanently wedge open a crack in longstanding political opposition to UBI, especially as the dire state of the global economy has pressured nearly every government to experiment with some form of it. Between March and June, 195 countries extended some form of pandemic-related benefits to their citizens, reaching 1.2 billion people, according to the World Bank. That includes the US, where the one-time stimulus payments of up to $1,200 that trickled out to most Americans since April, as well as beefed-up unemployment and food assistance payments, are the closest the country has ever come to UBI.

The pandemic is “the first time there’s a ton of investment in getting cash transfers to people all over the world, in a pretty big way,” said Tavneet Suri, an MIT economist who helped lead the Kenya study.

Prior to the pandemic, many recipients of the recurring payments in Kenya used the money to open small shops or other businesses, Suri said. When the pandemic hit, most of the families were able to keep their businesses open because they were being kept afloat by the payments—one of the study’s key findings. That means the families will have a leg up once the economy stabilizes.

In the early months of the pandemic, around the same time that Suri and her colleagues were collecting data in Kenya, a separate UBI study in California was also returning results that showed promise for food security. In that study, led by sociologists at the University of Tennessee, 125 low-income families in Stockton, California are receiving $500 per month for two years. The study began in February 2019 and is ongoing, but preliminary data show that by June of this year, the percentage of families able to prepare three meals per day rose from 32 to 75, despite the economic impact of the pandemic. In March, as lockdowns began, food accounted for nearly half of how the money was spent.

There are also signs that US stimulus transfers improved food security. When schools began to close, the government expanded access to food stamps to families with children through a new program called Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer, which was primarily meant to offset the loss of school-provided meals. Because the benefit rolled out at different times in different states, researchers at the Brookings Institution were able to compare rates of food insecurity in similar households with and without it. In July, they reported that in the first week after the benefit is initiated, the rate of hunger among children fell 11%—and that nationwide, the program likely lifted between 2.7 million and 3.9 million children out of hunger.

Lisa Gennetian, a Duke University economist who studies cash transfers, said she hopes that the pandemic can be a learning opportunity—not just about the benefits of cash transfers, but about how to provide them effectively.

Around 12 million Americans, for example, didn’t automatically qualify for the $1,200 stimulus check; their incomes are too low to require federal income tax returns, so the IRS required additional documentation before sending out the checks.

“One thing that was readily apparent to me the US just really lacks infrastructure to do this well,” said Gennetian. “Even once we had political will to get money out into the hands of people, we didn’t have a good mechanism to do that.”

The cumbersome bureaucracy meant that many of those 12 million families, a disproportionate share of whom are Black or Latino, didn’t know the benefit even existed, or struggled with the digital paperwork required to access it, said Seth Distefano, policy outreach director at the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy. Distefano has been giving virtual training sessions to local social workers on the steps to apply, in the hope that more families will finish their applications before the Nov. 21 deadline.

But even for those who can access the benefits, a single payment doesn’t go very far, according to the limited research on UBI. That’s another finding of the Kenya study: Families whose payments are spread out over a longer period tend to experience better health and hunger outcomes. Those households may be more able to take advantage of their income stability to make long-term investments.

In other words, in order for cash transfers to work best, they can’t be limited to times of crisis.

“UBI has a mentally and economically liberating effect,” Suri said. “Not having to worry about how to feed your kids every day makes you feel better. And if I don’t have to worry about all this other stuff, does that let me be the best version of myself?”