Are people having more panic attacks?

Editor’s note: This story contains descriptions of panic attacks. If you would prefer not to read those details, you can skip past them.

Editor’s note: This story contains descriptions of panic attacks. If you would prefer not to read those details, you can skip past them.

Tom was already not in a great head space at the beginning of the pandemic. The 29-year-old resident of Glasgow, Scotland had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder about four years ago, and was coming out of a major depressive episode when March’s lockdown orders kept him from his loved ones. “I’ve been fortunate that my family and friends have remained safe and well throughout this time, but my mental health has definitely taken a huge knock,” says Tom, whose name has been changed for this story. For the first time, he started to feel anxious pretty much constantly.

Then there were the panic attacks—heart pounding, pins and needles in his lips and hands, feeling like he’s losing control. The feelings would come in waves, gradually abating over the course of an hour. Tom had had panic attacks in the past, but never so intensely—in March and April, he would have 10 to 14 per week. “At first I wasn’t even sure what was happening to me, just that I felt I was completely losing my mind.”

He’s far from alone.

Panic attacks may be on the rise, as Covid-19 pushes psychological distress, anxiety, and depression to epidemic levels. Scrolling through mental health communities on Reddit (r/mentalhealth, r/PanicAttack) reveals hundreds of people who think they’ve experienced a panic attack, and have turned to the internet in need of answers.

The attacks themselves are not a mental disorder, and are different than a panic disorder in notable ways, says Mary Alvord, a psychologist with her own practice outside Washington DC. Panic attacks can happen in the context of psychiatric conditions beyond anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder—people with depression or obsessive-compulsive can have them, too.

Despite how scary they can feel, panic attacks are relatively common. Around a quarter of Americans without agoraphobia are estimated to have had one at some point in their lives, though Alvord suggests that figure might be up to 50%.

If you have one—and it’s not something else, like a side effect from medication or an actual heart attack—chances are you’re going to be OK, and your feelings are manageable. (If you have multiple panic attacks, or fear over having another panic attack gets in the way of their life, this may be a sign of panic disorder and you should seek help from a mental health professional.)

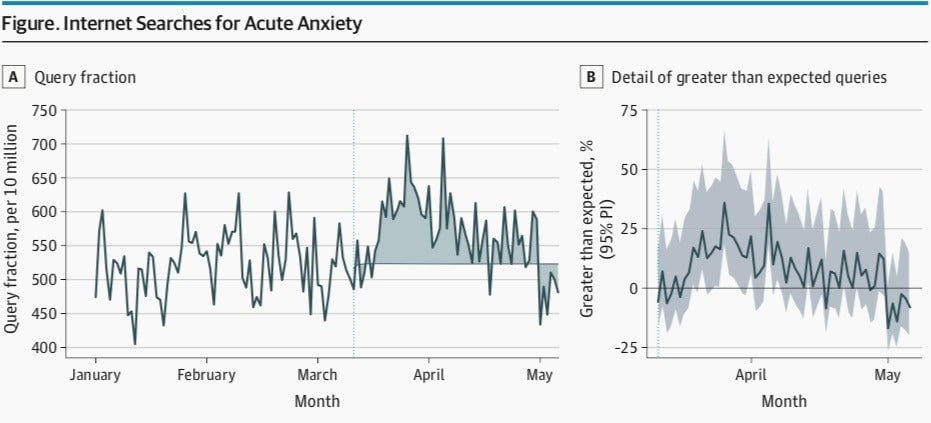

There are signs that more people could be having panic attacks. Two recent studies found an increase in Google searches for the term “panic attacks,” a preliminary indication that people might be having more of them.

But it’s harder to get clinical data. An uptick in panic attacks would not yet show up in hospital admission data or national public health information, if it’s tracked at all (because of fears of Covid-19 infection, people experiencing panic attacks may have been showing up less frequently to the emergency room in the first place, Alvord notes). “Unfortunately, we don’t have any current clinical data on the rise of panic attacks during the pandemic,” says a spokesperson from the Anxiety and Depression Association of America. The nonprofit advocacy group estimates it will take another year or so for that information to emerge.

Private companies offer little additional insight. A spokesperson from Lyra, a company that offers employee-based mental health services, says that though patients indicate greater mental health challenges, their company hasn’t seen any significant uptick in patients reaching out about panic disorder—an imperfect indication of panic attacks. Woebot Health, which makes an AI chatbot, doesn’t specifically ask people about panic, says chief clinical officer Athena Robinson. “But users express anxiety in many different ways, and they can use any word they choose,” she says. “So while we haven’t seen a significant shift in mentions of the word ‘panic,’ we do assess for anxiety generally, and what we saw as the pandemic started and lockdowns continued was a spike in anxiety levels.”

Despite the lack of concrete data, Alvord thinks it’s fair to say that it’s likely that there are more panic attacks. People are facing more mental health challenges during the pandemic—the sheer influx of patients to Alvord’s own practice, particularly those anxious around their own health, reflect that. More mental health issues make it more likely that symptoms like panic attacks have become more common.

The good news is that panic attacks are manageable, either on your own or with the help of a professional. If you do have a panic attack (and you’re sure it’s not something else), Alvord suggests holding your breath for a minute and slowly releasing it, and just reassuring yourself that it will pass.

If the panic attacks persist, it’s worth seeking the help of a therapist or psychologist. A professional can guide patients through a well-established treatment for panic attacks called interoceptive exposure, which involves inducing the symptoms of panic—hyperventilating, spinning to make you dizzy—to show the patient that everything is fine. There are also medications that can help.

Since reaching out to his psychiatrist about the new panic attacks, Tom has been able to get them under control. He hasn’t had one in a while, he says. Though he still suffers from anxiety, not worrying about panic attacks is an important step towards feeling well.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, in the US you can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 24/7, for confidential support at 1-800-273-8255. For hotlines in other countries, click here.