The financial crisis for US arts organizations has not been distributed evenly

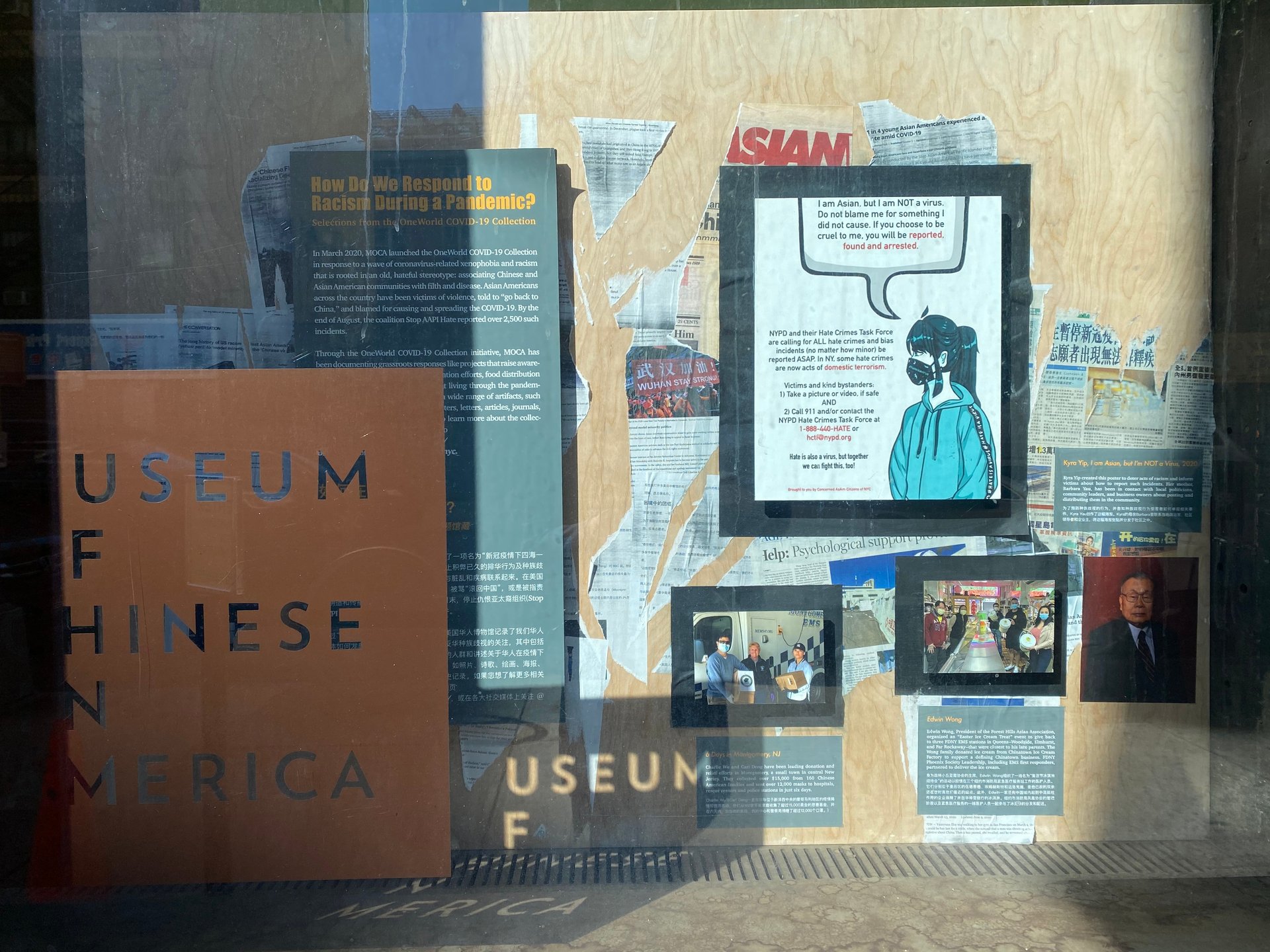

At the start of 2020, Nancy Yao Maasbach had a clear plan for how the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) in New York City’s Chinatown would increase and diversify its revenue. There were several private event bookings, the annual fundraising gala, and gift shop sales through a partnership with a local retailer. Low ticket prices and a pay-what-you-can policy meant that admissions only contributed about 3% to the museum’s annual budget.

At the start of 2020, Nancy Yao Maasbach had a clear plan for how the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) in New York City’s Chinatown would increase and diversify its revenue. There were several private event bookings, the annual fundraising gala, and gift shop sales through a partnership with a local retailer. Low ticket prices and a pay-what-you-can policy meant that admissions only contributed about 3% to the museum’s annual budget.

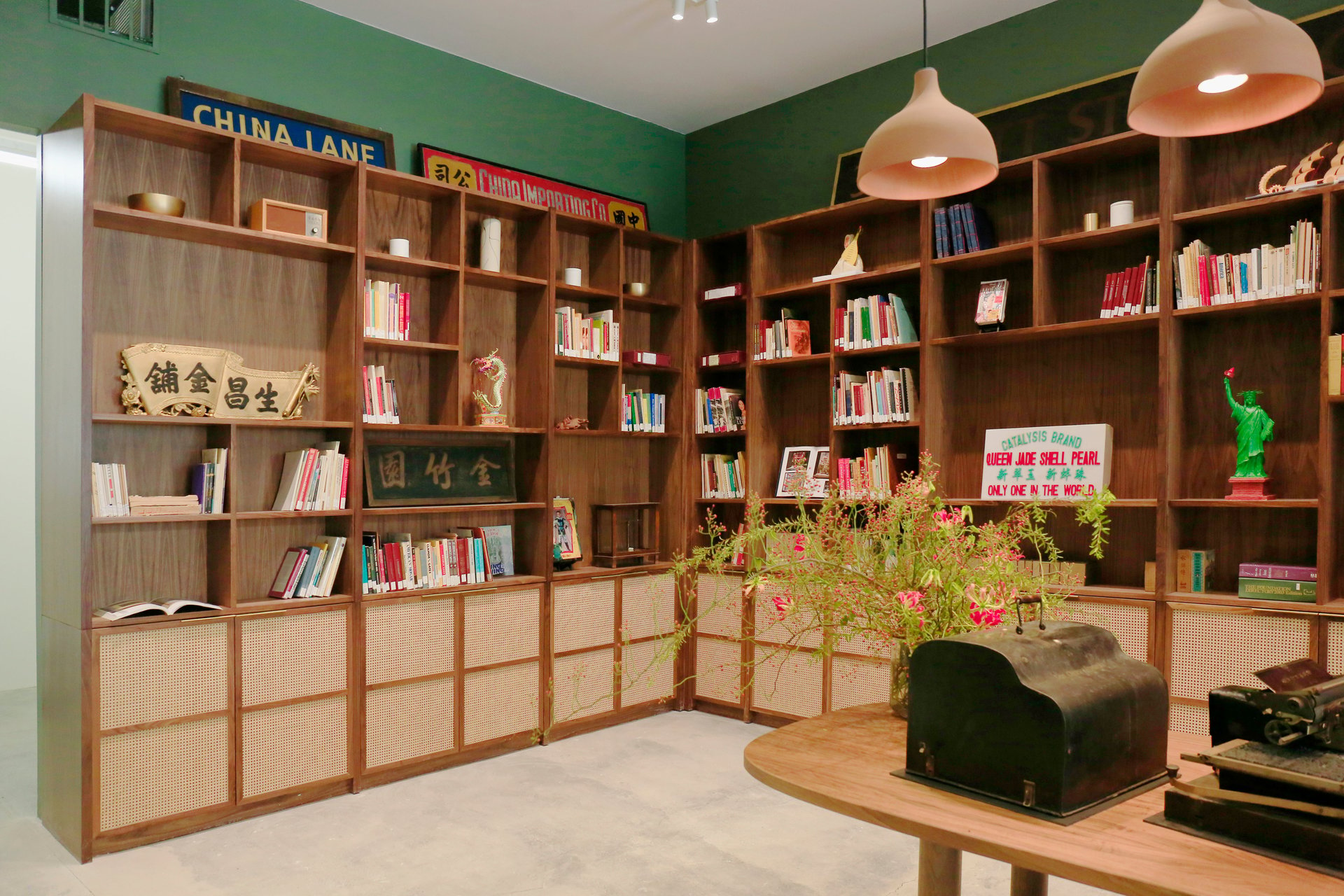

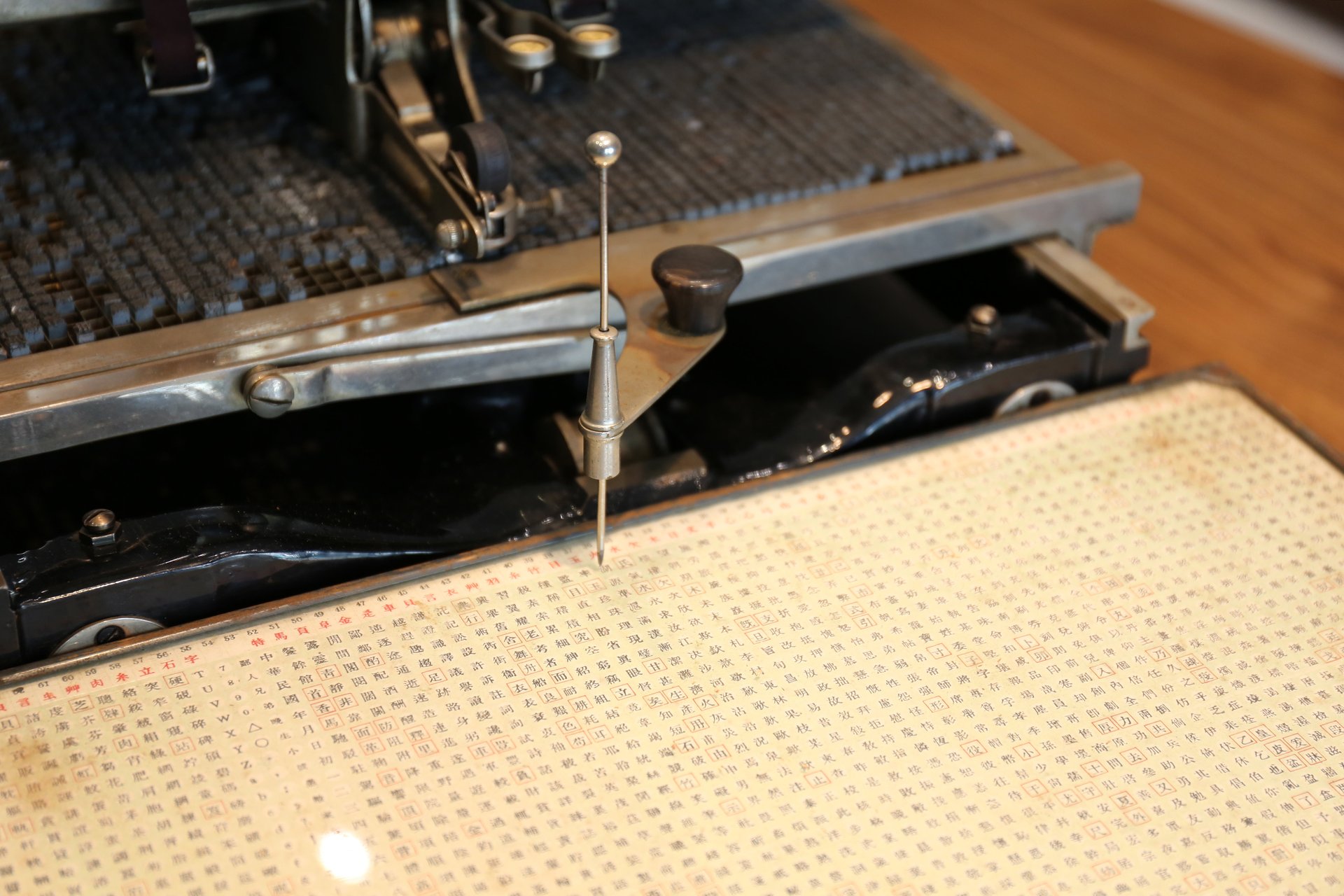

But in late January, there was a major fire in the building holding MOCA’s archives a few blocks away from the museum. Most of the organization’s 85,000-piece collection was recovered, but many items suffered water damage and did not have digital backups. The distinctive artifacts included Chinese folk art depicting eagles and other American iconography; an extremely rare Chinese typewriter from 1926 that can produce more than 70,000 Chinese characters; and the most complete collection of The Chinese American Times, a one-man operation by journalist William Yukon Chang, who began publishing the English-language newspaper in 1955.

A GoFundMe raised approximately $600,000 for repair and storage expenses. But the full restoration would cost millions, according to Maasbach, who has been president of MOCA for nearly six years after a career in investment banking, completing an MBA at Yale, and senior leadership roles at other non-profits.

While assessments were being made about the damaged items, MOCA tried to continue normal museum operations, including Lunar New Year festivities. Early February would normally be a busy time for MOCA and its neighborhood, but early concerns about the coronavirus pandemic fanned anti-Chinese sentiment and severely reduced the amount of foot traffic and activities in Chinatowns across the United States.

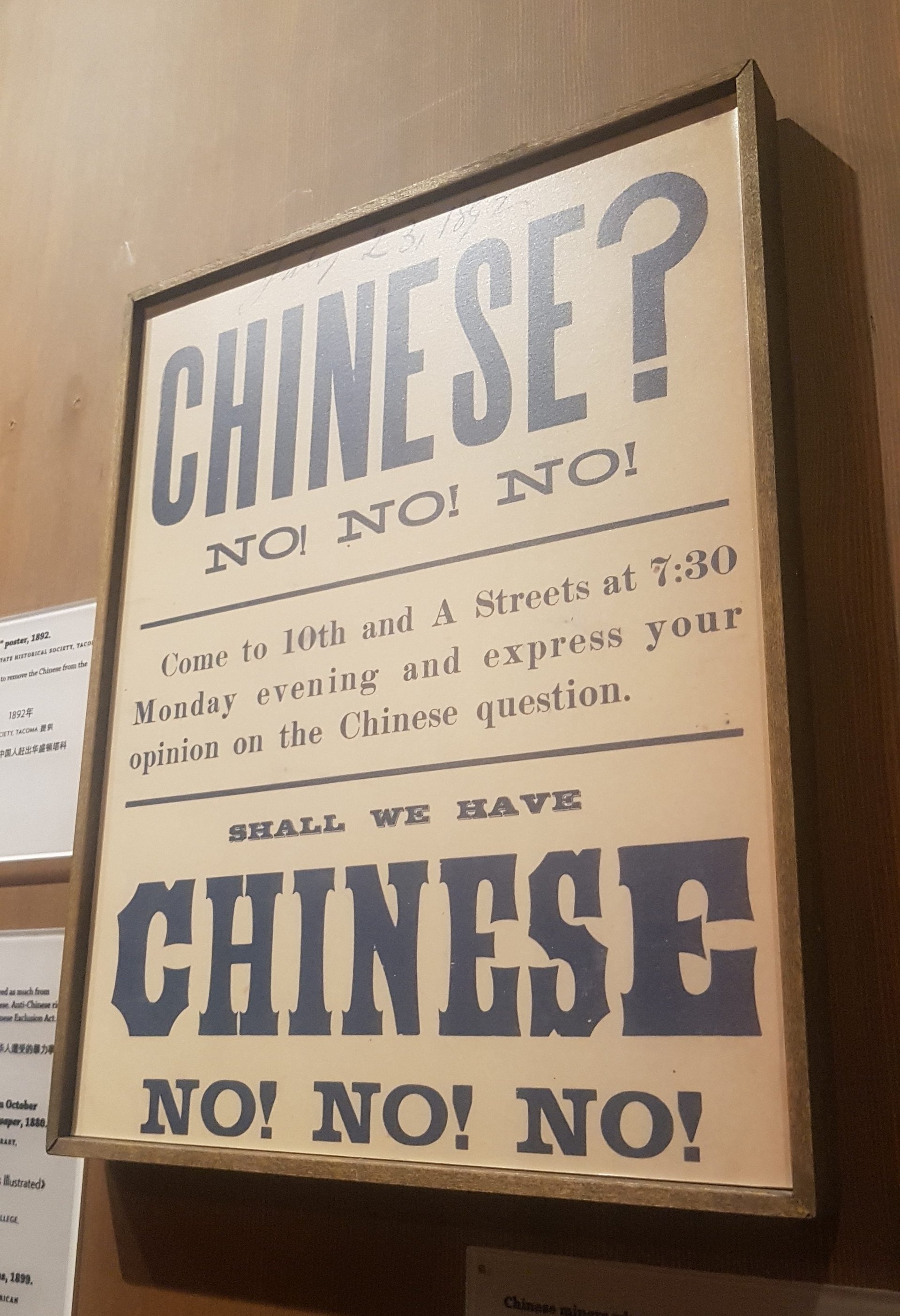

A few weeks after the fire, New York City was in lockdown to prevent the spread of Covid-19. Cultural institutions as small as MOCA and as big as Broadway could no longer hold ticketed performances, fundraising events, and other community activities. Amid rising anti-Chinese racism in the US, not unlike the messaging on the posters featured in her museum’s exhibit, Maasbach’s careful plan to grow revenue completely fell apart.

Severe pre-existing conditions

More than 900,000 people work in US arts nonprofits with budgets over $50,000, according to 2015 figures from Southern Methodist University’s National Center for Arts Research (now known as SMU DataArts). The struggle to pay for those staffers, along with other basic operating expenses, existed long before Covid-19.

“At the onset of the pandemic, the average arts and culture nonprofit had fewer than eight weeks of working capital,” says Brett Egan, president of the DeVos Institute of Arts Management (funded by US education secretary Betsy DeVos and her husband) at the University of Maryland. “The average American symphony had fewer than 15 days of working capital.”

However, the balance sheets between smaller arts organizations and larger ones are worlds apart. Institutions with budgets of $5 million or more make up 2% of American arts and culture non-profits, but receive more than half the revenue, according to a 2013 report published by the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy and the Helicon Collective, a consulting company.

The financial gap is even worse for nonprofits serving marginalized communities, like MOCA. The 20 largest mainstream US arts organizations have a median budget of $61 million, while the 20 largest serving communities of color have a median budget of $3.8 million, according to DeVos Institute research from 2015.

“Organizations serving communities of color, have, for decades, struggled to gain the same level of support from regional and national philanthropies as their ‘mainstream’ or ‘white’ counterparts,” Egan says.

Between March and May of this year, the DeVos Institute performed more than 400 free assessments of arts organizations across the country. Egan says that as venues stay closed or have only limited activity, the financial inequality between a small number of national organizations and everyone else has only become worse, especially for institutions serving Black, Asian, Hispanic and indigenous communities.

A drop in the bucket

The US arts sector did receive government assistance through the stimulus bill known as the CARES Act. The legislation allocated a combined $115 million to the grant-making National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for Humanities. The sector also received $1.8 billion in loans through the Paycheck Protection Plan (PPP). However, the assistance came to just a fraction of the $9.1 billion in estimated losses to arts organizations between March and July of this year, according to Americans for the Arts, a nonprofit based in Washington.

In New York City alone, the loss to operating revenues across roughly 800 arts organizations between March and early May of this year was estimated at $525 million, according to SMU DataArts.

Meanwhile, Egan says that “[m]any organizations of color, like many businesses run by people of color, were less successful in receiving PPP loans than organizations that had had longstanding, friendly relationships with banks that were able to leverage their power to get loans.”

Desperation for donations

Arts organizations quickly realized loyalty and interest from donors were essential to fighting off layoffs and their own survival, especially as they entered the seventh month of little to no activity.

Some Black nonprofits received a flood of donations following the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. For many small nonprofits, the challenge was continuing to compete with larger organizations with bigger marketing budgets, more staff, higher profiles, and longstanding relationships with major donors.

“Times have been desperate,” Maasbach said on a call with reporters. “This is by far the hardest job I’ve ever had. When you’re dealing with scarcity, and you’re dealing with a very important mission, and there’s urgency around what we want to do, it just magnifies the pain when you have trouble sustaining the organization.”

One report, published by the arts consulting firm TRG Arts, found 65 arts organizations in North America actually saw a 14% increase in the number of individual donations during the first six months of the pandemic compared to the same period last year. But overall donation dollars fell by 24%.

Philanthropy plays a bigger role

In late September, Maasbach received a call from the Ford Foundation, telling her MOCA was to receive a national grant as part of a program aimed at helping to sustain 20 American arts organizations serving communities of color. In total, MOCA will receive $3 million over four years, from a $156 million pool raised by 16 major donors and foundations, the Ford Foundation announced.

Maasbach compares the news to the birth of her first child and being given a winning lottery ticket because the funds are unrestricted—MOCA can use the grant in whatever ways they choose. She called it a “180-degree game changer” after recounting moments when the organization had trouble fundraising and wasn’t sure it mattered, prompting her to question the work that she did.

At $750,000 per year, the Ford Foundation grant would make up two-thirds of MOCA’s lost revenue from the canceled special events. “It stunned me,” Maasbach says. “To be honest, it was a 15 minute conversation, and I was in tears for about 11 minutes.”

Other organizations receiving funding from the Ford Foundation-led program are the Alaska Native Heritage Center, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, the Apollo Theater, the Arab American National Museum, Ballet Hispánico, the Charles H. Wright Museum, the Dance Theater of Harlem, East West Players, El Museo del Barrio, the Japanese American National Museum, Jazz at Lincoln Center, Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico, the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, the National Museum of Mexican Art, Penumbra Theatre, Project Row Houses, Studio Museum in Harlem, Urban Bush Women, and Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience.

A nightmarish future

Other arts organizations may be able to stretch limited budgets through creativity, entrepreneurship, sheer resilience, and volunteers. But as the pandemic rages on, their financial crises may get even worse due to public fatigue, lack of additional government aid, and probable cuts to local arts funding. “Cities like San Francisco, Austin, Texas, [and] Denver have been extraordinary funders of arts and culture activity,” Egan says. “But as you see real estate values in the retail and hospitality sector crumble, as you see people leave big cities for smaller cities and rural areas, you see the tax base diminish. Fiscal ’21 is going to be a nightmare for arts and cultural organizations that have historically received significant amounts of money.”

Public donations to arts, culture and the humanities made up less than 5% of charitable contributions in 2019, according to an analysis by the Urban Institute’s National Center for Charitable Statistics. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that households receiving stimulus checks this year earmarked an average 3% of the money for donations. But it is unclear whether Americans will continue to be as generous in the midst of a major recession, particularly in the absence of another stimulus package.

“There’s a very real chance that the organization that you love, down the corner, but have come to take for granted may not be there in a year,” Egan says. “So now is the time to step in.”