The CEO of a $1.2 billion space company can’t use its technology

The Russian founder of a business going public in a $1.2 billion transaction is not allowed to work with his own company’s products because of US rules intended to keep advanced space technology away from geopolitical rivals.

The Russian founder of a business going public in a $1.2 billion transaction is not allowed to work with his own company’s products because of US rules intended to keep advanced space technology away from geopolitical rivals.

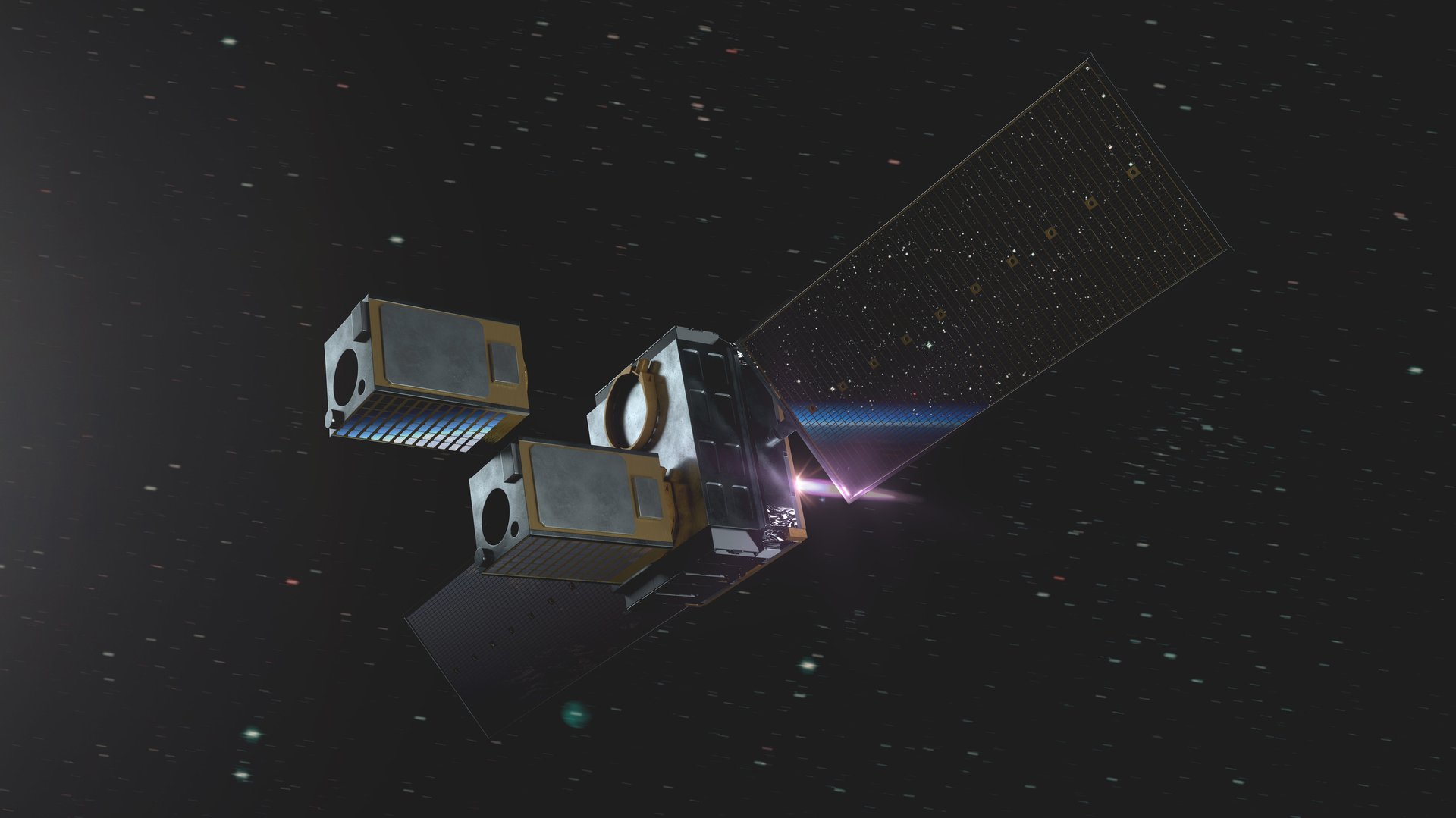

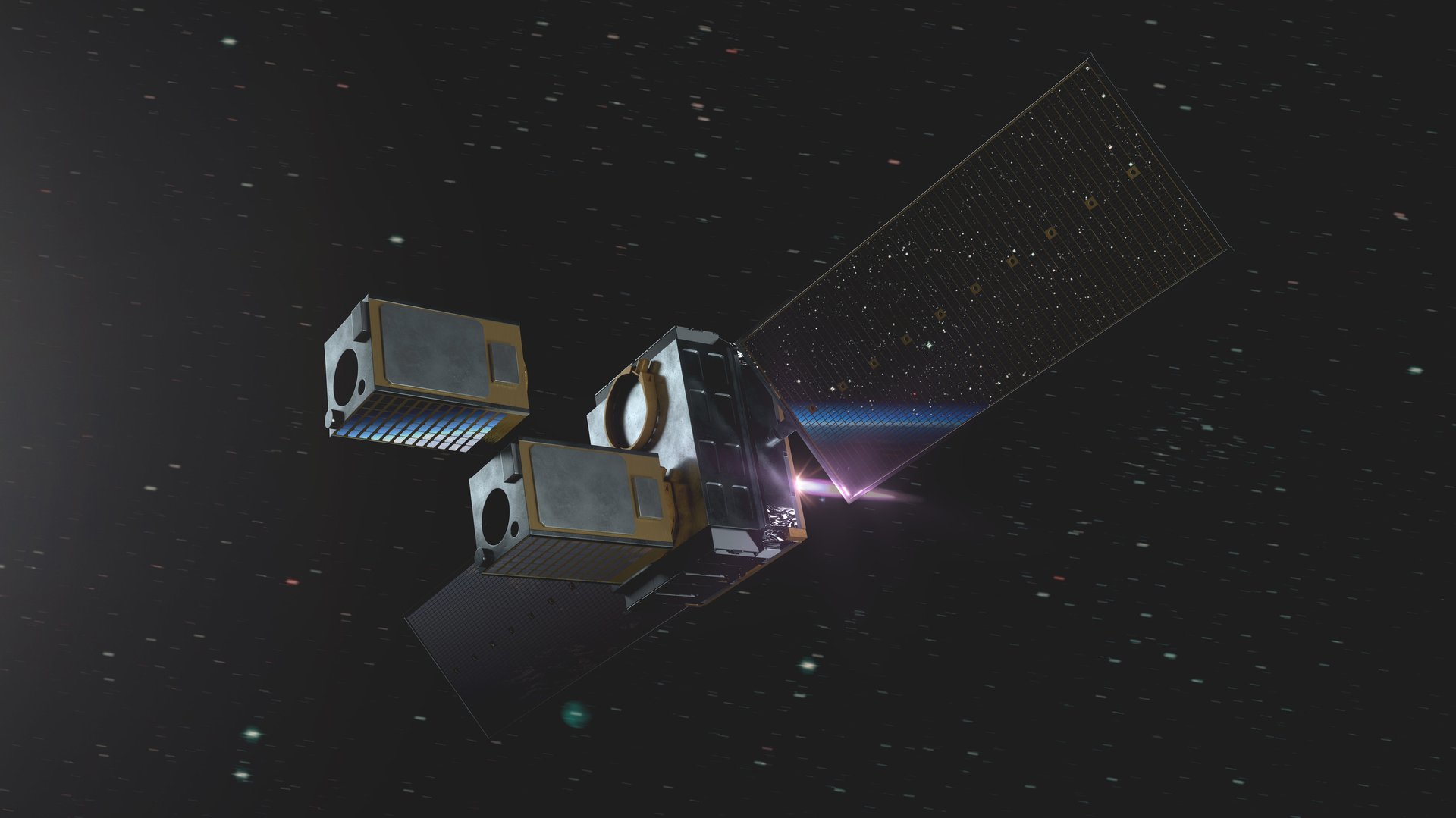

Momentus Space was founded in 2017 to develop a “last-mile” transportation system for satellites launched into orbit, using a novel water-based propulsion system. The company is expected to go public on the NASDAQ in early 2021 after a special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, created by the fund Stable Road Capital, purchased it in October.

Investors worry that the transaction may face unusual scrutiny because Momentus CEO Mikhail Kokorich, though credited with a majority of the company’s inventions, is legally barred from accessing the firm’s technology by US national security law, according to a Nov. 2 SEC filing. Kokorich did not respond to questions relayed to him by his spokesperson a week before this story was published. A spokesperson for Stable Road Capital said it would not answer questions about the transaction.

While executive leadership doesn’t always require technical chops, it’s hard to imagine SpaceX succeeding if it were against the law for Elon Musk to look at the rocket designs. This unusual scenario could bolster SPAC critics who say the method of going public lends itself to companies looking to avoid the scrutiny of a typical public offering in a frothy market driven by retail investors.

Developing cutting-edge space technology is a legally challenging business. Much of what makes the most advanced commercial satellites effective—microchips that can withstand the harsh environment of space, precision engineering and manufacturing, finely-calibrated sensors, and powerful software algorithms—is considered “dual-use” technology; that is, it has both civilian and military applications. The US government regulates this technology to make sure foreign governments don’t have access to it.

In 2019, Kokorich was the subject of a federal investigation to determine if he violated export control laws as an investor and executive in several satellite companies, according to four associates who were interviewed by federal agents. In 2018, the US government forced Kokorich to give up his ownership of another space company, Astro Digital, when it failed to pass a foreign influence review, according to three people familiar with the transaction.

Investigators asked about Kokorich’s access to satellite technology that, under US law, can only be used by citizens or permanent residents. The office of the US Attorney said to be supervising the 2019 investigation would neither confirm nor deny its existence, and Kokorich has not been charged with a crime.

However, the risk factors listed in the company’s prospectus acknowledge these challenges, noting that Kokorich “is not currently permitted to access controlled technology or hardware of the Company, which consists of certain technical information,” and that the company received a warning from the Department of Commerce for violating these rules in 2019. The company warns that its foreign control could make it difficult to raise new funds and acknowledges that Kokorich was forced to divest from his previous firm.

People who aren’t American citizens or permanent residents come under these rules because their access to the technology is considered a form of exportation. Still, foreign individuals can work at firms involved with dual-purpose technology, and foreigners can invest in them, too, if the Committee for Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS) approves it. This approval is often contingent on a formal mitigation plan that keeps specific executives and investors firewalled from technical data.

Kokorich’s first firm in the US, Canopus, was a joint venture with an American company called Stellar Exploration, founded in 2012 as Silicon Valley became a hotbed of space start-ups. Tomas Svitek, Canopus’ CEO, told Quartz the firm passed a US government review approving its foreign investors because it was managed by qualified Americans. According to internal documents, its backers would come to include a vehicle called “I2BF—RNC Strategic Resources Fund,” raised by Rusnano Capital, a Russian state-owned venture fund.

Canopus launched its first two small satellites in 2014, but Svitek became increasingly concerned about the company’s financing. The same year, worsening relations between Russia and the US after the invasion of Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea made life difficult for space companies seeking to do business in both nations.

Both issues came to a head in December, when Kokorich fired Svitek. He created a new company with Chris Biddy, an American Canopus engineer, transferring intellectual property and employees from Canopus to the new venture. It would eventually become known as Astro Digital and control the two Canopus spacecraft. After a legal dispute, Kokorich paid Svitek for his share of the company.

“I always treated them as investors,” Svitek said. “I guess he felt like he was more in charge of the company.”

Astro Digital faced the challenge of raising money while passing a government review of its work with restricted technology. Ultimately, after at least two attempts to pass a CFIUS review, Kokorich had to divest himself from the company and resign in 2018.

A lawsuit filed that same year illustrates the complexity of these financing arrangements. Dmitri Kushaev, a Russian national, sued Kokorich and Astro Digital, alleging that Kokorich had fraudulently diverted a $10 million investment intended for a different venture into the American satellite firm. This year, that case was submitted to arbitration at the International Chamber of Commerce.

License to innovate

Kokorich’s future with Momentus may depend on obtaining permission to work with its space vehicles.

Momentus could face significant repercussions if it cannot obtain an export license that would enable Kokorich to access technology covered by US export control laws, or if his immigration status cannot be changed to qualify him as a US person under those laws, according to Joseph Gustavus, an export control attorney at the firm Miller Canfield.

One route may be winning political asylum in the US. Kokorich, 44, began his career as Russia transitioned into capitalism, running a series of businesses as divergent as a mining services supplier and an electronics retailer. He founded Dauria Aerospace, billed as “Russia’s first commercial space firm,” in 2011, to develop small satellites for Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos.

He told the Wall Street Journal that he backed Russian opposition parties after Vladimir Putin came to power, and bankrolled their rallies in 2011 and 2012. Kokorich blamed political retaliation against Dauria for his decision to relocate to the US around 2015, but it’s not clear when or if he divested himself from the company. Ultimately, after production delays, two Dauria spacecraft were lost during a botched 2017 launch. In a legal dispute with Roscosmos over who was responsible, the agency won a $4.7 million court settlement, which apparently led the Russian firm to bankruptcy. Astro Digital lost two satellites on the same launch and collected on its insurance policy.

Former associates say they are skeptical that Kokorich is “the typical representative of the Putin exodus,” as Kokorich put it to the Journal, since important Russian figures continue to invest in his companies.

In 2018, Kokorich launched an investment fund alongside an investor in Astro Digital, Vadim Makhov, the former head of OMZ Group, a Russian industrial conglomerate controlled by Gazprombank. SEC records from 2019 show that one of the co-founders and major investors for Momentus Space is Lev Khasis, a top executive at state-owned Sberbank, Russia’s largest bank. Now, that stake is owned by Khasis’ wife. Both Gazprombank and Sberbank were sanctioned by the US government after Crimea’s annexation in 2014.

“It is possible that Mr. Kokorich’s controlling interests in the Company, or perceptions surrounding Mr. Khasis and his affiliation with Sberbank, could make it more difficult to obtain CFIUS approval in connection with future potential investments by the Company in U.S. businesses,” according to Momentus’ latest prospectus.

Another option for Kokorich is obtaining an export license that would give him the ability to work with controlled technology. In 2019, Momentus hired the lobbying firm K&L Gates to lobby on the issue of spacecraft export licensing. The lobbying contract was terminated in July 2020, but the recent SEC filing says Momentus is still seeking the license.

The move to take Momentus public through Stable Road Capital’s shell company could be a smart way for a risky high-tech business to tap public markets. The example of the space tourism firm Virgin Galactic, which successfully went public through a SPAC in 2019, provides a role model.

Still, some investors Quartz spoke to were surprised a three-year-old company was not seeking another round of private investment before tapping public markets. The $1.2 billion enterprise value projected by Momentus’ investors is ambitious compared to its forecast 2021 revenue of $19 million. And other, more established private firms like Rocket Lab and Spaceflight are developing their own space tugs that will compete with Momentus’ vehicles.

Correction: This article originally misreported the year Virgin Galactic became a publicly traded company.