The Russians are voting with their feet

A senior researcher at the Russian Academy of Sciences says he cannot survive on his monthly salary of $450. He has left Russia for a university in Japan. A family of four has purchased one-way tickets to Boulder, Colorado. They want to open a business and say the political and economic situation in Russia will not be resolved anytime soon. Fearing reprisal, prominent oppositionists like Garry Kasparov and economist Sergei Guriyev have announced their self-imposed exile. A poet says he is leaving because he cannot stand to see Putin on TV for the next decade—a common complaint. Pollution in metropolitan Moscow, foreign migrants, taxes, corruption, inflation—or stagflation, as the headlines scream—are some of the others.

A senior researcher at the Russian Academy of Sciences says he cannot survive on his monthly salary of $450. He has left Russia for a university in Japan. A family of four has purchased one-way tickets to Boulder, Colorado. They want to open a business and say the political and economic situation in Russia will not be resolved anytime soon. Fearing reprisal, prominent oppositionists like Garry Kasparov and economist Sergei Guriyev have announced their self-imposed exile. A poet says he is leaving because he cannot stand to see Putin on TV for the next decade—a common complaint. Pollution in metropolitan Moscow, foreign migrants, taxes, corruption, inflation—or stagflation, as the headlines scream—are some of the others.

As in previous times of uncertainty, people and capital are fleeing the motherland. Since 2003, some half a million Russians have left, with as many as 1.25 million working permanently or semi-permanently abroad in the last decade, according to Sergei Stepashin. Emigration is no longer so unthinkable or as much of a stigma as it was during Soviet times. Even those who are not planning to leave increasingly say they understand why fellow Russians choose to emigrate. Is this the start of another brain drain? Where are Russians going?

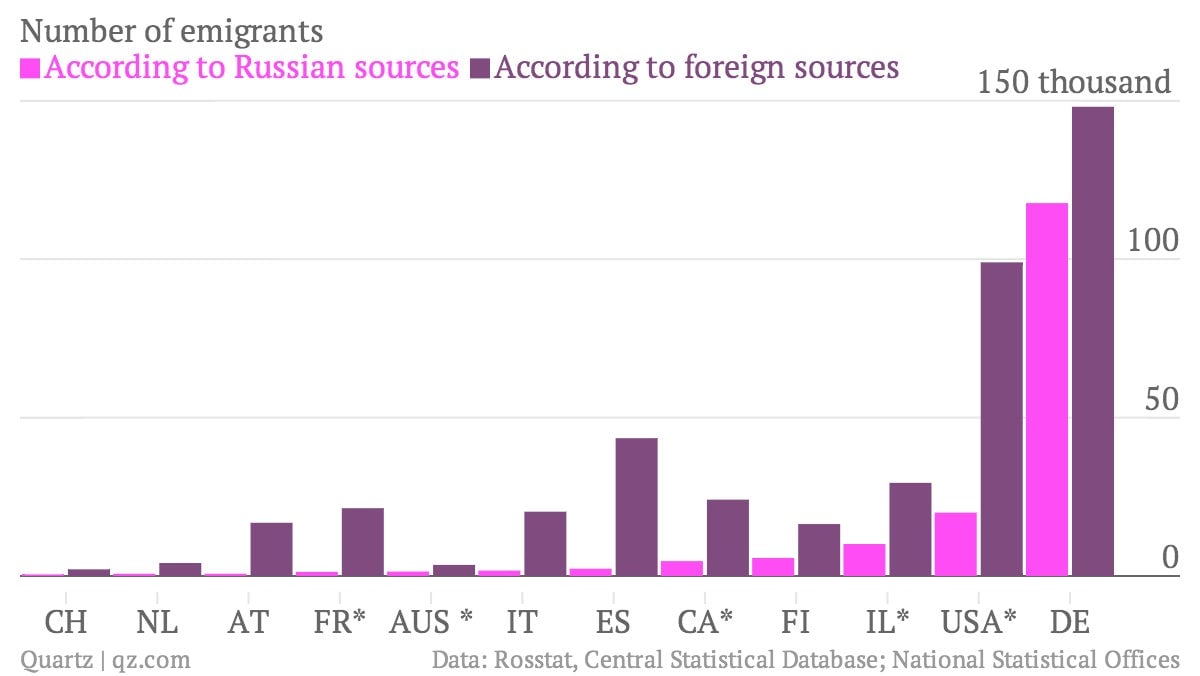

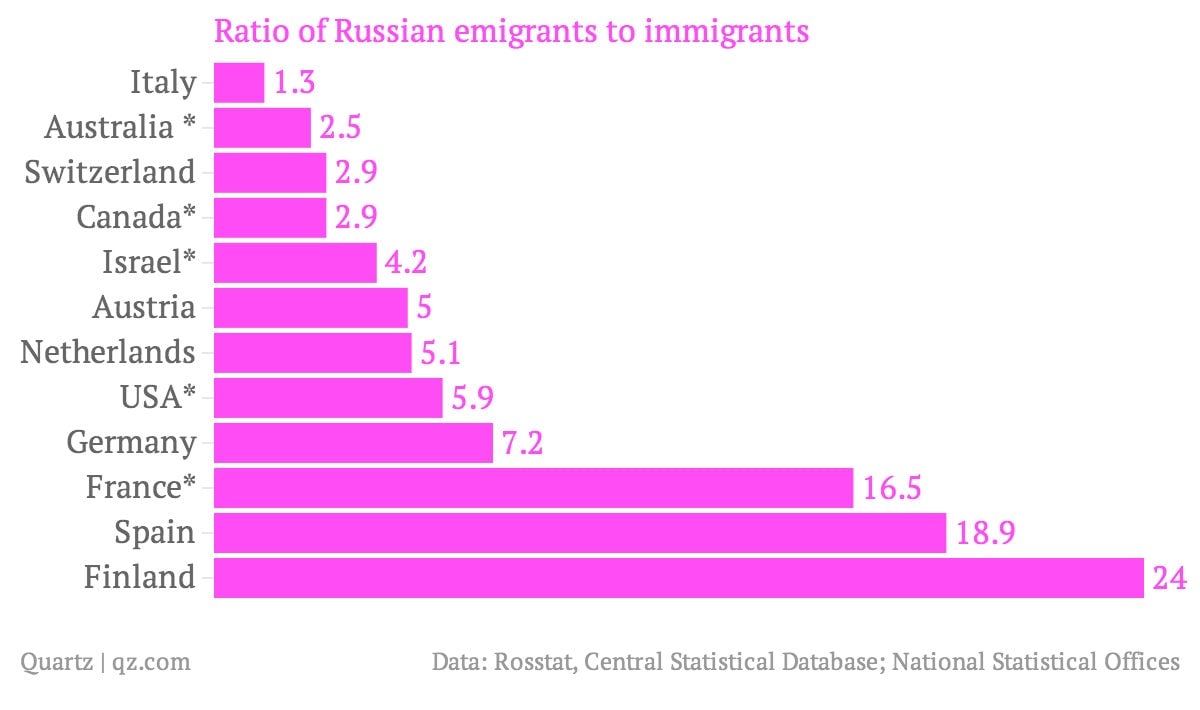

There are two sets of numbers here, those according to Russia and those according to the rest of the world:

The two obviously don’t align, with Russian totals vastly underreporting outflows by a factor of about 2.7. Spain, for example, should have about 43,500 Russian nationals. Russia says there are only 2,300. Are the Spanish inventing Russians where they don’t exist, or is Rosstat making up data? The Spanish, like the Italians and the Danes, have no incentive to overestimate the number of Russians living within their borders. Russian officials, on the other hand, can stem a growing demographic crisis at home with mere numerical legerdemain.

One perhaps intended consequence of US president Ronald Reagan’s decision to welcome Soviet Jews in the 1980s was the resulting exodus of educated professionals, by which America ostensibly gained and Russia ostensibly lost. With a negative birth rate and shorter life spans as compared to the West—about 64 years for men, with a quarter dying before 55—Russia’s population is ill-equipped to cope with another loss of those hardest to replace. The winners, again, will be Western countries like England and Germany, where Russian scientists have settled and published, and Israel, where (non-Jewish) Russian doctors have come to study and practice.

Distrust, suspicion, and cynicism have risen along with oil prices as the high cost of petroleum has buoyed the Russian economy, not innovation. Capital gains in foreign markets have not improved things at home, nor has basic infrastructure fared well even in the boom years. Far from being able or willing to reinvest, the government can only pay its bills if oil stays well above $100 a barrel. But the rate of growth in certain industrial sectors does nothing to guarantee political rights like freedom of speech, for example. Nor has the rest of Russian society kept pace with its economic development. A broad cross-section of Russians have been left behind to dream about grass growing on the other side of the globe. So it should come as no surprise that some of them are voting with their feet, predominantly young people and women: More than 80% of Russian nationals in Italy are women. The figure in Western Europe and Australia is only slightly lower than that.

Of course, many Russians do not or cannot leave. According to a study by the Levada Center, 83% of Russians said they did not have an international passport in 2012. Yet the same survey showed that about half of all students would like to emigrate, with a slightly higher rate for entrepreneurs. Improbable though they may be, these are the aspirations of well-to-do Muscovites, not the traditionally marginalized village and urban poor, or the liberal intelligentsia. If the children of oligarchs and a majority of the elite already live and study abroad, and the youngest and most successful aspire to leave for the most mundane reasons, how unsatisfied must the least privileged be—those who have little to gain even if things go well?

Rising inequality in Putin’s neo-Soviet experiment will not be tempered by superficial adjustments. Only fundamental reforms to a corrupt system that has shown itself incapable of redistributing wealth or distinguishing between who should be punished and who rewarded will suffice. For those eligible to travel, it is the casual indifference of the state that stings most.

After events in Kiev and the Kremlin’s response in Crimea, Kasparov and Guriyev seem less like alarmists. Any outward-bound Russian of the so-called Sixth Wave would do well to take with them this telltale farewell, a nesting doll of sarcasm, courtesy of current Prime Minister Medvedev:

“Godspeed to those who leave,” he said.