The ways to understand US election results

There are dozens of ways to interpret election results. Commentators, journalists, and political staffers will contort themselves to find trends and ascribe meaning to the results in the hours, days, and weeks following the US presidential election. So here’s a guide to understanding which votes “decided” the election and which ones were merely cast in it.

There are dozens of ways to interpret election results. Commentators, journalists, and political staffers will contort themselves to find trends and ascribe meaning to the results in the hours, days, and weeks following the US presidential election. So here’s a guide to understanding which votes “decided” the election and which ones were merely cast in it.

Swing states

In swing states, opinion polling shows there is no candidate with a large lead. While the electoral votes from states that consistently vote for the Democrat or Republican candidate count just as much as electoral votes from any other state, candidates typically can’t win the presidency without also winning at least one swing state. That dynamic results in the majority of campaign efforts being focused in these states where the results could go either way. Gaining a larger margin of victory in a Democratic or Republican stronghold like Oregon or Arkansas, respectively, doesn’t increase the number of electoral college votes a candidate receives, but winning just one vote more than the other candidate in Pennsylvania nets 20 out of the 270 electoral votes needed to win the presidency. Viewed through the lens of swing states, winning the overall election is possible only through victories in closely-polling states.

Swing counties

A microcosm of the nation on the whole can be seen inside swing states. Some counties are populous enough to affect statewide results, while others are dense with voters of a key demographic for both campaigns. Kent County, Michigan—the area around Grand Rapids—is seen as a swing county as is Erie County, Pennsylvania. Candidates visit these places because it allows them to spread their message efficiently. Of course, every vote in a state counts exactly the same. But, like swing states, when there are expected results from some places and less certain results from others, the votes in closely-polling places can be framed as being the deciding votes in a state.

Bellwether counties

By reflecting the national electorate at large or by random chance, bellwether counties are those places where a majority of residents have voted for the eventual winner of the election in successive prior years. There have been 19 counties that have voted for every presidential-election winner since 1980:

- Warren County, Illinois

- Vigo County, Indiana

- Bremer County, Iowa

- Washington County, Maine

- Shiawassee County, Michigan

- Van Buren County, Michigan

- Hidalgo County, New Mexico

- Valencia County, New Mexico

- Cortland County, New York

- Otsego County, New York

- Ottawa County, Ohio

- Wood County, Ohio

- Essex County, Vermont

- Westmoreland County, Virginia

- Clallam County, Washington

- Juneau County, Wisconsin

- Marquette County, Wisconsin

- Richland County, Wisconsin

- Sawyer County, Wisconsin

Through the lens of the bellwether, correlation is causation, and thus the winner of these counties will go on to win the presidency. While all of these were just as much bellwethers during the last presidential election, so too were Ventura County, California, and Bexar County, Texas. The difference is voters in Ventura and Bexar preferred Hillary Clinton in 2016—they got it wrong—and thus are no longer bellwethers. You should expect some of the bellwethers to prefer the loser.

Exit polls

Pollsters will set up shop outside of voting locations on election day and ask voters leaving the polls to fill out a survey about who they are and who they voted for. Those surveys can then be statistically weighted to the demographics of the area and compared with the results at that voting location. Exit polls allow us to understand the election through demographics. How did college educated white suburban women vote? The exit poll can tell you. What was the most important issue for Trump voters in Colorado? The exit poll can tell you. That is, if you trust them.

Exit polls also provide estimates about how certain places voted before the votes counts have been posted (but after the polls have closed). That was a problem in 2000. Based on exit polls and early, incorrect results, TV networks called the wrong winner in Florida.

Edison Research conducts exit polling for a consortium of news organizations: ABC, CBS, CNN, and NBC. To capture the intent of voters who voted by mail, Edison conducts surveys by phone to augment its in-person results.

On election night in 2016, the Associated Press—then a member of the consortium—abandoned the exit poll results to project winners, because of how far the data deviated from the vote tallies they were seeing. It instead relied only on actual results.

The AP left the consortium after the 2016 election and in 2018 announced that it was launching its own post-vote survey that it said would better address the historic inaccuracy of exit polling.

Correlations to other factors

Even without exit polls, correlations can be made between election results and the prevailing demographics of an area. By joining election results with data from the Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Agriculture, and other sources we can find trends. For instance:

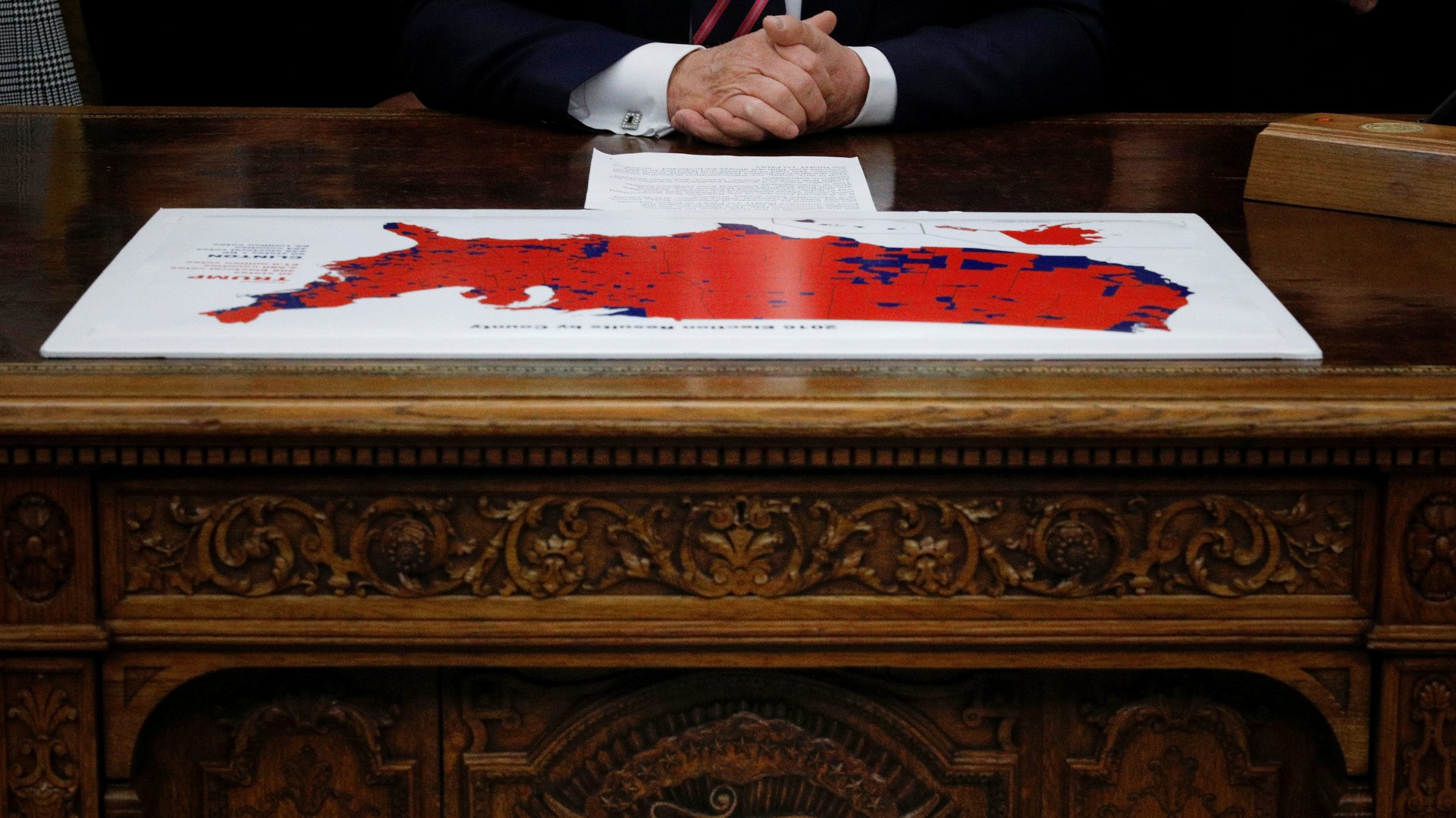

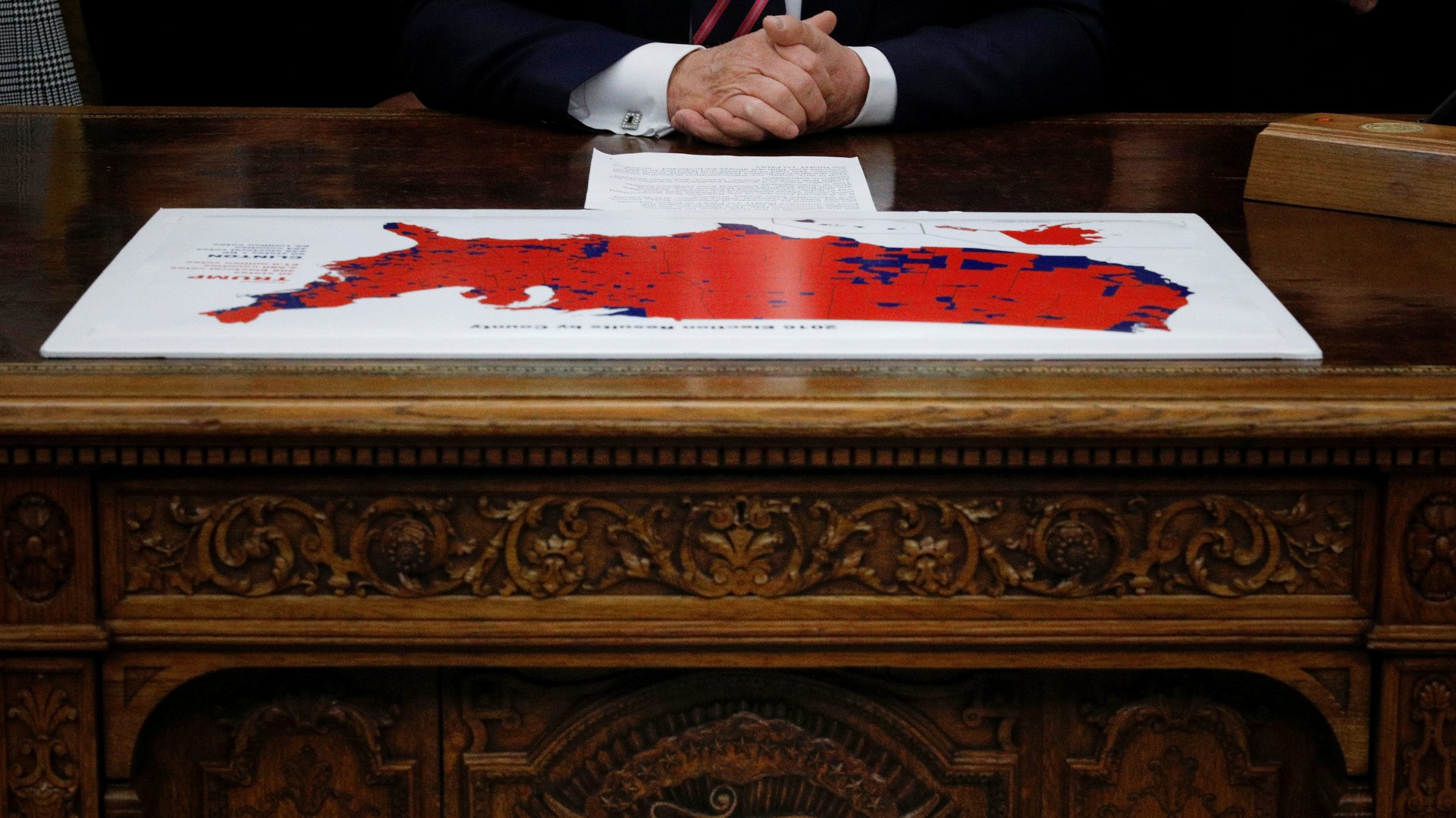

- Urban vs rural vs suburban areas. In recent years, rural areas and urban areas have been diverging ideologically, leaving medium population-density places like suburbs as the areas that can be viewed as deciding the election. Because of their large numbers, voters from urban areas—depending on whether or not they vote—can of course tip the scales in a state, too.

- White vs non-white populations. The US presidential preference is correlated with the density of white people in a county. With about 60% of the US population identifying as non-Hispanic, non-Latino white people, shifts small shifts in their preferences can be seen as deciding the election.

- Level of education. In 2016, Trump’s success with voters who didn’t graduate college—irrespective of income—became a primary way to understand his victory.

- Economic conditions. National and state-wide economic trends can obscure local ones. Employees of declining industries or people experiencing local recessions can be seen as tipping the balance in some states.

Shifts from prior elections

Since US voters’ choices are effectively binary—Democrat or Republican—the election campaign and results can be viewed as a near zero-sum game of shifting voters from one column to the other. This lens makes clear which areas have soured on the incumbent’s party or attracted to it. A more nuanced view of voting shifts might also include considerations for older voters dying, younger voters becoming eligible to cast ballots, migration into or out of an area by certain groups of people, and voter turnout.

Whatever the reason, using this lens means the only way to win is by shifting the proportion of voters from the incumbent party to the challenging party, or preventing it.

Split ticket voting

Every presidential ballot will have at least one other federal election on it and in some places more. When a voter picks a presidential candidate from one party and a House or Senate candidate from another, it’s called a split ticket. Low numbers of split-ticket ballots can be seen as a reflection of personal political polarization and the non-overlapping appeal of party platforms. Large amounts of these divided ballots can reveal dissatisfaction with a specific candidate that overcomes a voter’s party preference. If a presidential candidate is able to win lots of split-ticket ballots, it could be viewed as the result of successfully appealing to independent voters—those that aren’t affiliated with a political party. If those split ticket victories occur in the swing states the candidate wins, it could be framed as the deciding factor of those wins.

Voter turnout

High levels of broad-based, bipartisan turnout is seen as a measure of “enthusiasm” about the election, and to a certain extent the ease of the voting process.

Because white people and older people are historically more likely to vote, turnout is often framed as whether younger and non-white people cast ballots. Through this understanding, when the preferred candidate of Black, brown, and young people wins, it can be attributed to those people voting if their turnout numbers are larger than typical. Of course turnout from other demographic groups drive election results, and total voting numbers, too.

Large turnout is one factor in the perception of whether the winning candidate has a “mandate”—that the country at large supports the winner’s plan for the country.

Viewed through the prism of turnout, the people who didn’t vote in the last election are deciding this one. When turnout favors one of the candidates, or prior-election voters abstain, it means that those skip-election voters can be seen as tipping the balance.

Vote by mail, and pre-election-day voting

Hand-in-hand with voter turnout is pre-election-day voting and voting by mail. Some states are periodically reporting the number of voters who have returned their mail-in ballots or have already voted ahead of election day. Many states made voting by mail easier this year in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

If there is a…

- Partisan split between a state’s in-person and vote-by-mail ballots, and

- The incremental reporting of counted ballots on election night does not report in-person and vote-by-mail ballot results at the same time…

…the trend of the partial vote counts reported soon after polls close could differ dramatically from the final vote tallies states certify after all the ballots are counted.

Lines at polling places

Partially a function of turnout turnout, partially a measure of voting capacity, and partially an indication of the competence of election officials, the lines that develop at polling places are a bit of a Rorschach test of election watching. Is a long voting line a sign of intentional voter suppression or the result of officials not anticipating (or caring about) a historic number of voters?

Perhaps there wasn’t a line all day, but now people have finished work and are all coming to vote at the same time. The length of ballots is different around the country because of the varying number of coinciding state and local elections. Filling out longer ballots takes more time.

If an area uses electronic systems to verify a voter’s eligibility and is hard to use (or fails), it will cause delays.

This year, some polling places are periodically closing to disinfect and clean.

A line on its own gives little insight into its causes. But combined with knowledge about the distribution of election resources in a jurisdiction, and the history of lines at certain polling places, certain inferences can be made about the care and attention officials have given to making sure every person who is eligible to vote feels welcome and is able to do so.