The 90-year-old strategy that could end the US unemployment crisis

Herbert Hoover was a man who had great faith in business. The private sector had propelled the US to prosperity in the early part of the 20th century, and Hoover—a mining engineer turned financier turned politician—had reaped the benefits of capitalism firsthand.

Herbert Hoover was a man who had great faith in business. The private sector had propelled the US to prosperity in the early part of the 20th century, and Hoover—a mining engineer turned financier turned politician—had reaped the benefits of capitalism firsthand.

The 31st US president stuck to this view even as he governed the country during the early years of the Great Depression, confident in the resilience of the private sector. “The sole function of government is to bring about a condition of affairs favorable to the beneficial development of private enterprise,” Hoover declared in 1931, as bread lines grew and Americans evicted from their homes poured into shantytowns. Under this logic, federal intervention was best kept to a minimum.

As the Great Depression dragged on, Hoover’s confidence in the power of business and “rugged individualism” to provide for the American public proved misplaced. He did launch some federal programs aimed at relieving the crisis. But there simply weren’t enough jobs to go around during the Great Depression. Ultimately, to get people working again, the government had to invent some.

The Works Progress Administration was born in 1935 under Hoover’s successor, Franklin Roosevelt. Over the next eight years, the federal jobs program would put 8.5 million Americans to work, with nearly 40% of unemployed people participating in the WPA at its peak.

Today, in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, the US is navigating another enormous economic crisis. And once again, the question of whether the private sector can be relied upon to provide Americans with the work they need is being put to the test.

“It’s tragic that it takes a crisis like this to shake the cobwebs out of people’s thinking and open up the possibility for new thinking,” says David Riemer, co-founder of the New Hope Project, a well-regarded WPA-style program aimed at helping the working poor in Milwaukee. “The existing safety net, it’s clearly not up to the job of giving people the employment or income they need to weather what might be a long storm.”

The pandemic unemployment crisis

The official unemployment rate in the US fell to 7.9% in September, the lowest level since the onset of the pandemic. But that number includes only people who are actively looking for full-time work. As MarketWatch noted, the decline from the prior month “mostly reflected 700,000 people exiting the labor force because of a scarcity of new jobs.”

Under a different measure of unemployment, which includes people who can only find part-time work and people who’ve grown discouraged in their job search and are no longer actively applying for work, the September rate was 12.8%.

There’s reason to worry that things will get worse before they get better. Mass layoffs are still cropping up at companies like Disney and United Airlines, with more businesses expected to make cuts in coming months as the spikes in Covid-19 cases across the US continue to take a toll on the travel and hospitality industries, among others. One economic paper from the University of Chicago estimated that 42% of jobs lost to the pandemic aren’t coming back. And some economists, including New York University’s Nouriel Roubini, who predicted the collapse of the US housing market during the still-heady days of 2006, further argue that while the economy may get a temporary bounce, it’s ultimately heading toward a second Great Depression that will decimate the job market for years to come.

As such dark possibilities loom, it’s time for policymakers to start thinking big. That includes considering what a new WPA could look like in the coronavirus era.

What was the WPA?

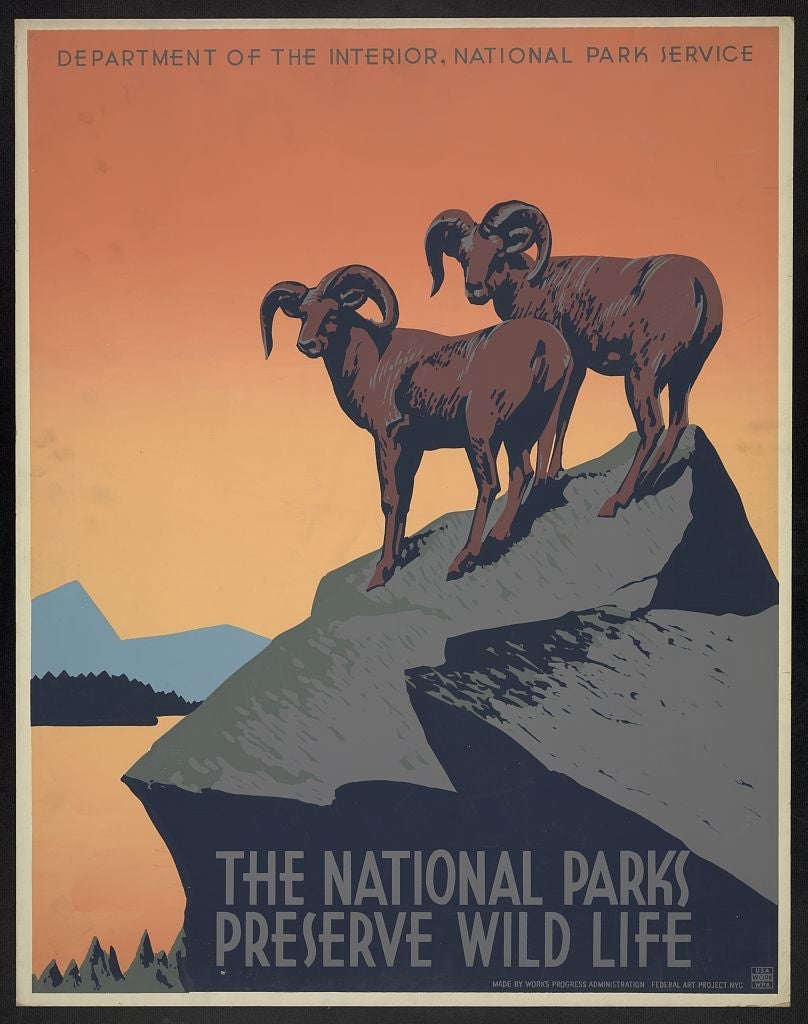

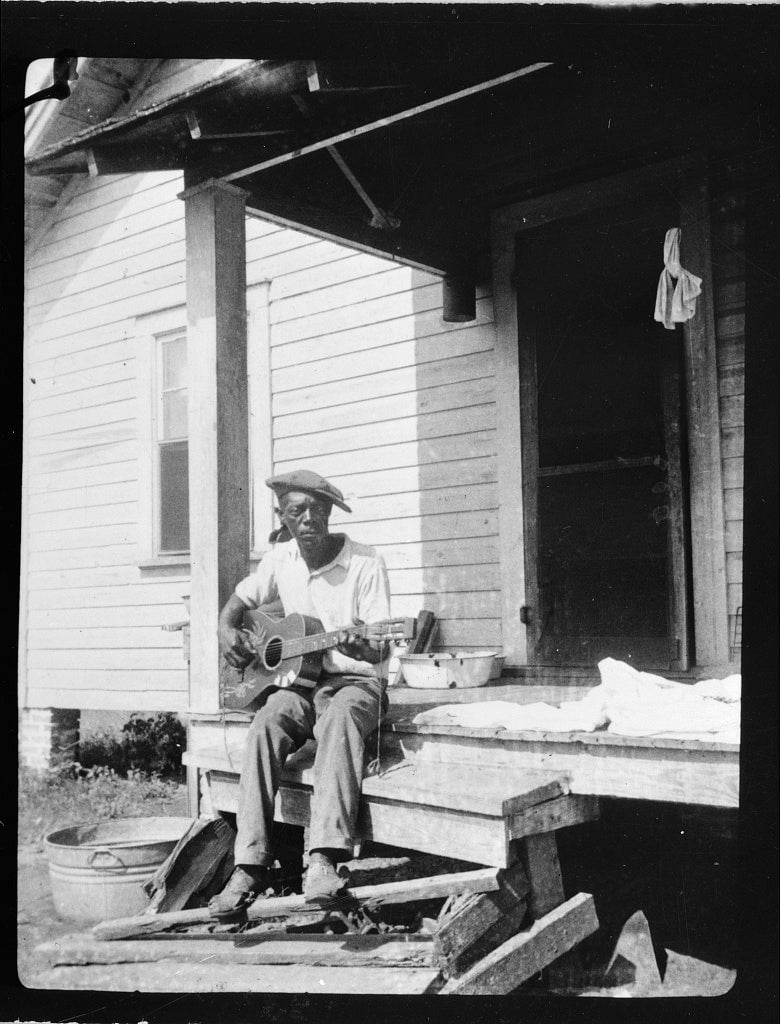

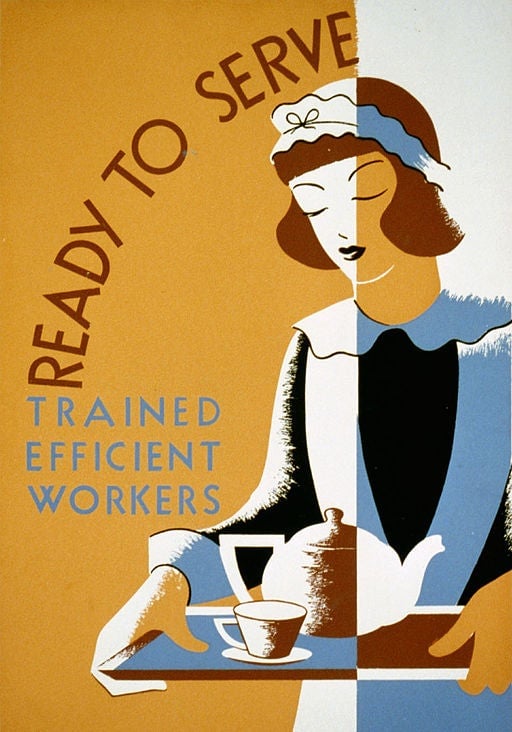

The WPA was a wildly controversial program during the Great Depression. A hallmark of Roosevelt’s New Deal, the program put Americans to work building roads, airports, bridges, parks, and New York City swimming pools; serving hot lunches, creating mathematical tables, and running nursery schools; teaching free classes, painting murals, interviewing former slaves, and delivering library books on horseback to rural communities. Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, and John Cheever worked for the WPA. So did Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

But a lot of people hated it. Critics accused the program of paying people to spend time on useless tasks, coddling workers, flagrantly overspending, and taking the country to the brink of straight-up Communism. The word “boondoggle,” still in use today to refer to work of little value, first came to prominence as slang for WPA projects.

Many of the same criticisms would likely be mounted at any attempt to recreate the WPA on a national level today. Moreover, Republican lawmakers have held that the solution to the current unemployment crisis lies primarily in supporting the private sector. Citing concerns about the US budget deficit, they pushed a $500 billion “skinny stimulus” deal that was blocked by Senate Democrats.

Nonetheless, some Democratic senators have already begun pushing for federal jobs programs. In June, Tammy Baldwin (Wisconsin), Cory Booker (New Jersey), Ron Wyden (Oregon), Chris Van Hollen (Maryland), and Michael Bennet (Colorado) proposed legislation for a permanent government-subsidized transitional jobs program, with a companion bill later introduced in the House of Representatives. Lawmakers in New York and Massachusetts also are pushing for WPA-style programs at the state level.

The current political balance of power in the US means that the chances of successfully passing a national jobs program seem slim. But that could well change with the upcoming November elections. Notable advocates of the idea include descendants of Roosevelt and other architects of the New Deal, who endorsed a WPA reboot in an open letter to presidential candidate Joe Biden.

“We can do it,” says Gregory Acs, vice president of income and benefits policy at the left-leaning think tank Urban Institute. But “the longer we wait to commit, the less timely it will be, and the more the need will grow.”

Right now, there are 12.6 million Americans officially unemployed, another 7.2 million who want a job but aren’t actively searching, and 6.3 million who are working part-time but want full-time work. In order to employ 40% of people in need of work, as the WPA did, a new national scheme would have to create about 10 million jobs.

Why unemployment insurance isn’t enough

Federal jobs programs are one of several levers that countries can pull in the event of mass unemployment. Germany’s Kurzarbeit system allowed businesses to keep workers on even when the economy crashed, with the government temporarily footing the bill for part of employees’ salaries. The UK, Australia, and Japan have similar programs to Germany’s, and Denmark’s government unveiled a variation of the plan in March.

In addition to a round of stimulus checks of up to $1,200 per person early in the pandemic, the US has thus far relied mostly on unemployment insurance as a solution for people who’ve lost their jobs. Until the end of July, Americans had access to beefed-up unemployment insurance (including an additional $600 in weekly benefits) and other emergency measures as a result of the CARES Act passed in response to the coronavirus crisis. But Congress allowed those emergency measures to expire, and has yet to pass a new stimulus bill. More CARES Act benefits for the unemployed, including eligibility for gig and self-employed workers and an extra 13 weeks of extended unemployment insurance for people who’ve run through their standard state relief, are set to run out at the end of the year unless Congress extends them.

Unemployment insurance is a vital, lasting legacy of the New Deal. But proponents of government-subsidized job programs say that it’s not enough, on its own, to address job shortages.

In essence, unemployment insurance is intended to sustain people who need money to get through a gap in work while they job-hunt. A subsidized jobs program serves a complementary purpose: It’s meant to address situations where there aren’t enough available jobs for all the people who want one.

The goal of a jobs program is “to place people who likely wouldn’t otherwise be employed into jobs that otherwise wouldn’t exist,” explains Indi Dutta-Gupta, co-executive director at the Georgetown Center on Poverty & Inequality.

Recent successes with subsidized jobs programs

While the WPA was the largest-scale subsidized jobs program that the US has ever undertaken, there are other, more recent examples of successful schemes.

On the large-scale level, India has a federal jobs program called the National Rural Employment Guarantee, which offers people in rural areas up to 100 days of paid work per year on public works projects. Research shows the program increased household consumption (and, by extension, living standards), prompting people to spend on more nutritious foods and to purchase more durable goods (like housing and cars), livestock, and equipment.

Smaller US programs have also launched in the decades since the WPA. One such program, among the most well-regarded by policy experts, was The New Hope Project, which served two low-income neighborhoods in Milwaukee, Wisconsin during the 1990s. Drawing on funding from the state and federal government as well as anti-poverty organizations, New Hope placed unemployed people in community service jobs while offering benefits like subsidized childcare.

The program was “a way to address there not being enough jobs and the kinds of pervasive discrimination against individuals based on either skin color or background,” says Julie Kerksick, one of the co-founders of New Hope, who is now a senior policy advocate at Community Advocates’ Public Policy Institute.

Not only did New Hope help people get work when they needed it, it may have also had additional benefits over the long term. One randomized evaluation of the program found that five years after the program had concluded, children of parents who had participated in the program were more engaged at school and more likely to be preparing for careers than their control-group counterparts.

New Hope primarily improved adults’ employment situations during the years in which they participated in the program. But the evaluation did find that adults who had previously faced barriers to finding work (such as having an arrest record, lacking a high-school degree, or being a parent to young children) continued to experience increased levels of employment and income years after the program’s conclusion. That suggests subsidized job programs may be particularly useful for society’s most marginalized populations—the very people who are most likely to be buffeted by the current crisis.

What jobs does America need?

A new WPA would have to differ from the 1930s version in several important ways. For one thing, as long as Covid-19 continues to be a major public health threat, the jobs on offer would have to be ones that could be conducted with minimal risk of infection—whether involving remote work, jobs that could be done outdoors, and jobs that entail heightened safety and testing measures.

A Brookings Institution article published earlier this year by Apurva Sanghi and Michael Lokshin outlines a few possibilities for government-subsidized remote work. People could get jobs digitizing documents (only 10% of the world’s books are available electronically), labeling data in order to train artificial intelligence programs, or conducting virtual services aimed at helping to alleviate loneliness, depression, and anxiety.

Earlier this year, the House of Representatives introduced a bipartisan bill that would create a national public health corps, with jobs supporting contact tracing, testing, and vaccination efforts. The bill hasn’t made much progress, but Dutta-Gupta points out that such a program could also be a way for the US to expand these services while keeping costs comparatively low. “If you can save money by doing something like contract tracing [as a subsidized job program], the ROI could be enormous,” he says.

Federally subsidized jobs tailored to the ongoing childcare and education crisis in the US would also be a major boon—for both unemployed Americans, and for Americans who are lucky enough to still have jobs but are struggling to work and parent at the same time. “Can we take some of the folks who are out of work who have strong literacy and numeracy skills, and hire them as effectively teachers’ aides?” Acs says, pointing out that they could offer online tutoring services or simply read with younger kids online. Subsidized jobs facilitating affordable housing construction or infrastructure projects that mitigate the impact of climate change would be another helpful option, he says.

There are also aspects of the WPA that ought to be avoided at all costs. The WPA of the 1930s “reflected and reproduced the dominant racial and gender order,” as Eileen Boris and Jennifer Klein write in their history of the home health workers’ labor movement, Caring for America. Only one person per household was allowed to hold a WPA job, a rule that typically benefited men. Racial discrimination was a real factor, Boris and Klein write, noting that while the WPA created 38,000 housekeeping jobs, in “Southwestern states, Mexican American citizens obtained household aide positions”—that is, assisting in the care of sick or needy people—”while African Americans only received instruction in domestic service.”

William Spriggs, professor of economics at Howard University and the chief economist for union federation AFL-CIO, recalls discovering that the Norfolk Botanical Garden in Virginia was transformed from a swamp into a stylistic marvel by 200 black women and 20 black men on assignment by the WPA. The working conditions were harsh: As the garden’s website recounts, they labored from dawn til dusk, in overwhelming heat and in freezing temperatures, carrying “the equivalent of 150 truckloads of dirt by hand to build a levee for the surrounding lake” and completing “the back-breaking task of clearing trees, pulling roots and removing stumps.” In the WPA, “the dirtiest, ugliest job” was often assigned to the most marginalized US citizens, Spriggs notes.

The design of a new federal jobs program, based on Riemer’s takeaways from New Hope and other jobs programs he’s helped create since the 1990s, could mitigate the risk of bias. Under his recommendations, workers wouldn’t be assigned to a detail. Rather, they would apply for whichever specific government-subsidized jobs they want and be interviewed for them, giving both workers and employers agency over the process.

Still, Spriggs says that he would prefer that solutions to the pandemic-era jobs crisis more closely mirror that of countries like France and Germany, wherein the government helps prevent layoffs by subsidizing pay. “If you’re learning the lessons from the Great Depression,” he says, the focus should be on issues like allowing workers to organize, creating labor standards, and paying people adequate wages.

“The lesson isn’t oh, the WPA was so wonderful,” he says. Rather, it’s that the US should have kept updating and building upon the worker protections introduced by the New Deal, so Americans wouldn’t be in a position where they need a WPA at all.

The rules for a successful jobs program

Riemer and Kerksick say that in order for a contemporary federal jobs program to be successful, it would be important that it closely match the experience that workers would have in any other job—with the main difference being that the government would be the one issuing paychecks. Riemer also recommends that anyone who wants to enroll in a jobs program be allowed to do so, regardless of income level. The rule is intended in part to avoid the stigma that’s often associated with welfare or other schemes aimed at people living in poverty.

Among the other important elements of a good jobs program, according to Riemer: Work assignments should have a time limit, in order to prevent employers from relying upon workers they essentially get for free from the government rather than adding new workers to their own payroll. And the pay should be minimum wage, lest the subsidized programs become more attractive to workers than typical employment. The goal is to ensure that the programs don’t compete with private-sector jobs, but rather function as a stopgap.

Riemer and Kerksick emphasize that these are only one piece of the puzzle in addressing poverty and unemployment. Beefed-up unemployment insurance is also crucial, they say, as is raising the minimum wage. So too is it necessary to have support systems in place for those with disabilities or caretaking responsibilities that prevent them from working.

“Having access to work is necessary, but it’s not always sufficient to getting out of poverty,” says Kerksick. “Even a job, even 40 hours a week, and frankly even at a higher minimum wage, will for many people not be enough. You need an earning supplement, you need affordable childcare.”

Still, Kerksick and Riemer say that subsidized jobs programs are necessary—and not just in moments of nationwide economic crisis. Riemer’s book, Putting the Government In Its Place: The Case for a New Deal 3.0, argues it’s almost always the case that there are more people who want work than there are jobs available. He says this structural issue is a big part of the explanation for the persistent problem of poverty and unemployment in the US, in addition to oft-cited problems such as systemic racism in education. “The good news, I suppose out of all this, is that going forward it’ll be awfully hard to deny that we’ve got big problems with the very structure of the labor market,” he says.

The purpose of work

A WPA for the pandemic era would serve a number of important purposes beyond simply helping people to stay afloat during an unprecedented crisis. For one thing, unemployment is linked to all kinds of negative effects on people’s physical and mental health.

For another, Acs points out, “the long-term unemployed have a harder time getting back to work.” Research suggests this is true for several reasons: employers are wary of hiring people with big gaps in their resumes, and may worry that their skills are less up-to-date. Unemployed people may themselves start to flag in their job search after experiencing so much rejection. A subsidized jobs program would help people avoid all of those issues.

On a deeper level, work is a major part of many people’s identities, giving them a sense of purpose and meaning—whether that involves taking pride in helping others, relishing the act of daily problem-solving, or feeling satisfaction in being able to provide for themselves and their families.

“I believe with all my heart and a lot of experience that people generally want to be a part of creating things, making things, fixing things, or doing things,” Kerksick says. At New Hope, she recalls, the promise to participants in the jobs program was: “If you want to work, I guarantee that I can help connect you with work.”

That kind of pledge could make a big difference to a lot of people now.