Three ways the US CDC can regain the public’s trust

Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, it seems that, for the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), almost everything that could have gone wrong has.

Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, it seems that, for the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), almost everything that could have gone wrong has.

Issues with CDC-designed test kits, combined with supply shortages, meant the country was slow to start testing for Covid-19 when other countries were doling them out at scale. President Donald Trump’s administration relieved the organization of its customary duty of collecting data and prevented its leaders from addressing the public. As the pandemic wore on, Trump reportedly pressured the agency to soften mask requirements and offer misleading information about school reopenings and testing guidelines, while his administration visibly flouted the CDC’s recommendations.

Within a few months, the organization upon which other countries modeled their own public health entities has been so maligned and undermined that public trust in it has eroded. By September, a poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that just 67% of US adults had “a great deal” or “a fair amount” of trust in the CDC, compared to 83% in April.

But that’s not the end of the story. Even if the CDC’s prestige has declined in recent months, there’s still time for it to regain the public’s trust—and likely save lives in the process.

“We have the worst public health emergency our country has faced in a century, and we need the top public health agency in the country to lead us out of it,” says Howard Koh, a professor of the practice of public health leadership at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and the former assistant secretary for health for the US Department of Health and Human Services. “The agency has always been extremely well regarded until this latest crisis. Its [reputation] can be and must be restored immediately.”

Here are three ways the CDC could restore its reputation as the premier public health agency in the world—work more likely happen under future president Joe Biden.

Depoliticize

One of the most effective ways that Trump and his administration have undermined the CDC is by making its recommendations political. Take, for example, the recommendation to wear face coverings. Though wearing masks has been proven to reduce the spread of Covid-19 in the US and many other countries, Trump has refused to do so publicly and mocked those who do, an attitude his supporters have emulated.

It’s easy to see how repeated behavior can cause a rift across political viewpoints. But how to de-escalate it?

Strong, pro-science leadership would help, says John Holdren, science advisor to president Barack Obama and director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy from 2009 to 2017. “What was the secret to…bringing science and tech to bear on the full array of issues in [Obama’s] agenda? The single most important thing is a president of the US who understands something about science and tech, who understands how and why they matter, and who empowers people across departments and agencies to do their jobs, to follow the science and engineering they need to tell the truth,” Holdren says, who now holds multiple appointments at Harvard. “A president with those characteristics will appoint highly capable people to the key positions, and they will in turn recruit capable people to deputy and line positions.”

The CDC, which is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, was somewhat protected from political influence by not being in Washington DC, says Tom Frieden, former director of the CDC who is now president and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives, a global initiative focused on heart health. “Up until now, there was only one political appointee in the CDC. The Trump administration sent down eight. That’s probably not a good thing,” Frieden says. “Fundamentally you need to think about some possible safeguards against undue political influence.”

It’s particularly important to get people to see past their partisan differences now, as the Covid-19 crisis continues to present a threat. And though pro-science candidate Joe Biden can lead in a way that gives credence to science and scientists, it will take a lot of work to heal the partisan divide. “We can control [the virus] if we recognize we’re all in this together,” Frieden says.

Increase communication

In moments of crisis during his tenure in the White House, Holdren remembers jumping into the situation room with all the experts present. “Obama made clear from the beginning that the most capable scientists we have are going to be in the room, and when they’re not enough we in the room are expected to reach out to others across the country. We did that again and again, on issues of public health, of nuclear safety, on environmental issues like the oil spill in the Gulf,” he says.

No one made an attendance list per se, but it was clear to all that Obama trusted the heads of his agencies to give him the best information possible to inform policy. “Invariably if health policy was on the agenda, Tom Frieden was in those discussions,” Holdren says. It’s clear to him that this kind of communication has not been happening under Trump’s tenure. Frieden has estimated that he made 250 or 300 trips to Washington.

That communication between the president’s science advisors and the CDC head is critical in more relaxed times, too. “When Tom Frieden was the head of the CDC, he and I had lunch together at least once a month,” says Holdren. “When Tom Frieden had ideas, my job was to make sure the president heard them.”

For his part, Frieden emphasizes the importance of having CDC officials communicating public health information directly with the public. “I don’t know how many briefings I did over Zika, Ebola, [and] H1N1,” Frieden says. “Those briefings are really important. You’re able to tell people what you know when you know it, what you don’t know, and what you’re doing to try to figure it out. You get good questions from the media. You may recognize based on those questions that there are things you thought you had explained clearly that you hadn’t, questions you hadn’t anticipated having to answer that you do have to answer.”

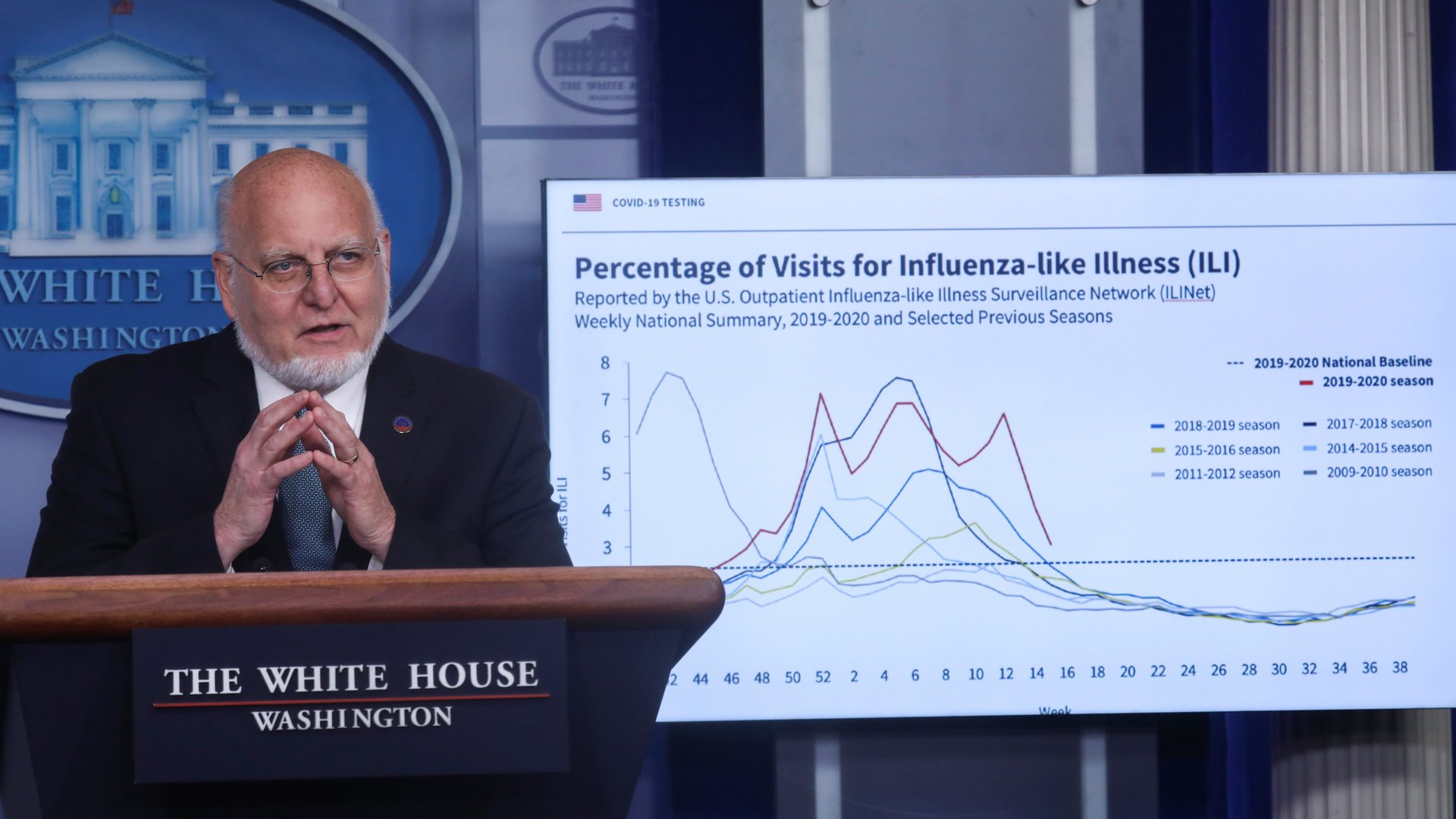

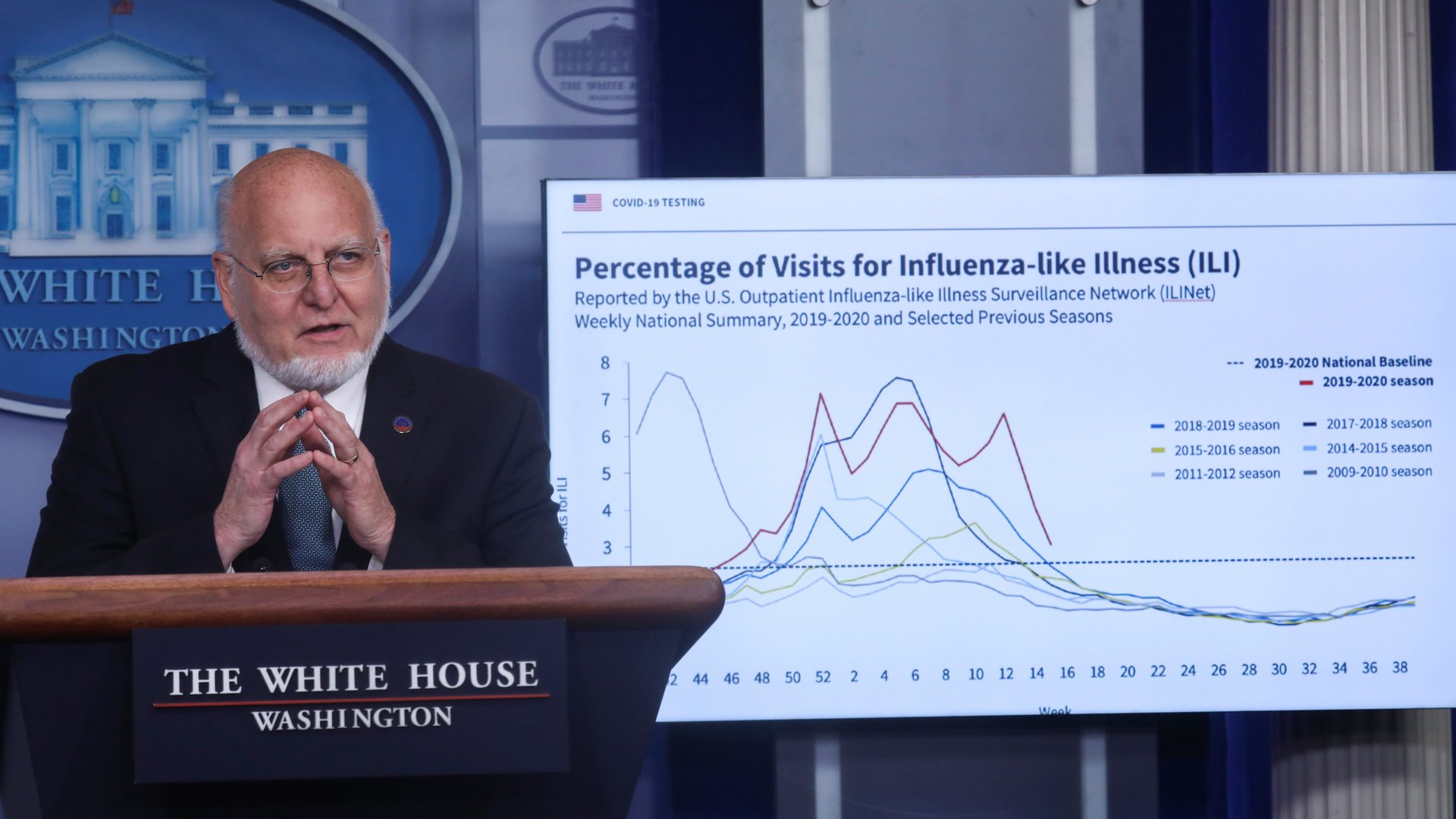

Though Trump had some coronavirus briefings early in the pandemic, few public health leaders—including Robert Redfield, the current head of the CDC—were given the opportunity to speak. The president discouraged questions from the press, insulting the reporters who asked them or ending briefings early. The most recent White House press briefing around coronavirus was in August. “The absence of that kind of regular media briefing takes a very heavy toll,” Frieden says.

“In every crisis in the last administration that I was part of, CDC leaders and Dr. Anthony Fauci [the nation’s leading infectious disease expert] were front and center,” says Koh, adding that studies show that people place particular trust in doctors and scientists in public health emergencies. “That communication was direct, an essential part of the response process. It’s been concerning to see its rapid decline in recent years. I’m hoping it can be just as rapidly reversed.”

Regain control over the data

One of the biggest criticisms of the CDC has been its inability to collect accurate data about the pandemic. The problem may have been exacerbated by rapidly changing directives from the White House coronavirus task force.

The task force reportedly wanted to get complete daily data from hospitals; something CDC officials hadn’t been able to accomplish because of the diversity of the datasets coming in. Usually, CDC scientists release completed data once they have a chance to polish it up with statistical methods. But instead, by insisting that the agency switch to collecting hospital data via a private company owned by a major Republican party donor, the quality of Covid-19 data declined even more.

One of the best things the CDC could do now would be to engage in complete transparency around its data, says Heather Mattie, a data scientist at Harvard’s school of public health. This could mean publishing data immediately and explaining why there are gaps or inconsistencies, or it could mean explaining the thought process behind recommendations. Public health guidelines should evolve along with the science supporting them; explaining how that science and data changes over time can help increase trust in those updates.

Brooke Nichols, a health economist and infectious disease mathematical modeler at Boston University, proposed another idea: “I might convene a board of scientists that are external to the CDC,” she says. These independent scientists may be charged with figuring out how to restore separation between the CDC and the White House and rehabilitate trust in its scientific objectivity.

So how do we get there?

Trust is not something that can be rebuilt in a day—or with a single presidential election. But there’s still something the CDC can do to make progress: address the public health crisis in front of it.

“The CDC will not regain credibility until it solves the pandemic in the US—or until it’s part of the solution,” says Reuben Granich, a public health consultant who formerly worked with the CDC, WHO, and UNAIDS on HIV treatment and prevention.

Ending the pandemic, of course, won’t happen with a flip of a switch. Instead, Granich says that what the organization and those around it really needs is an OODA loop—a military strategy that stands for “observe, orient, decide, and act.” Rather than trying only to try to fight the pandemic, CDC leaders will have to assess why things have gone so wrong, and then pivot from there.

It’ll take humility—and ideally, more than a bit of urgency.