How far will Uber take its new legal framework for gig labor?

Regulators and labor groups around the world have been pushing hard for higher pay and worker protections in the gig economy. But in California, they got totally outflanked.

Regulators and labor groups around the world have been pushing hard for higher pay and worker protections in the gig economy. But in California, they got totally outflanked.

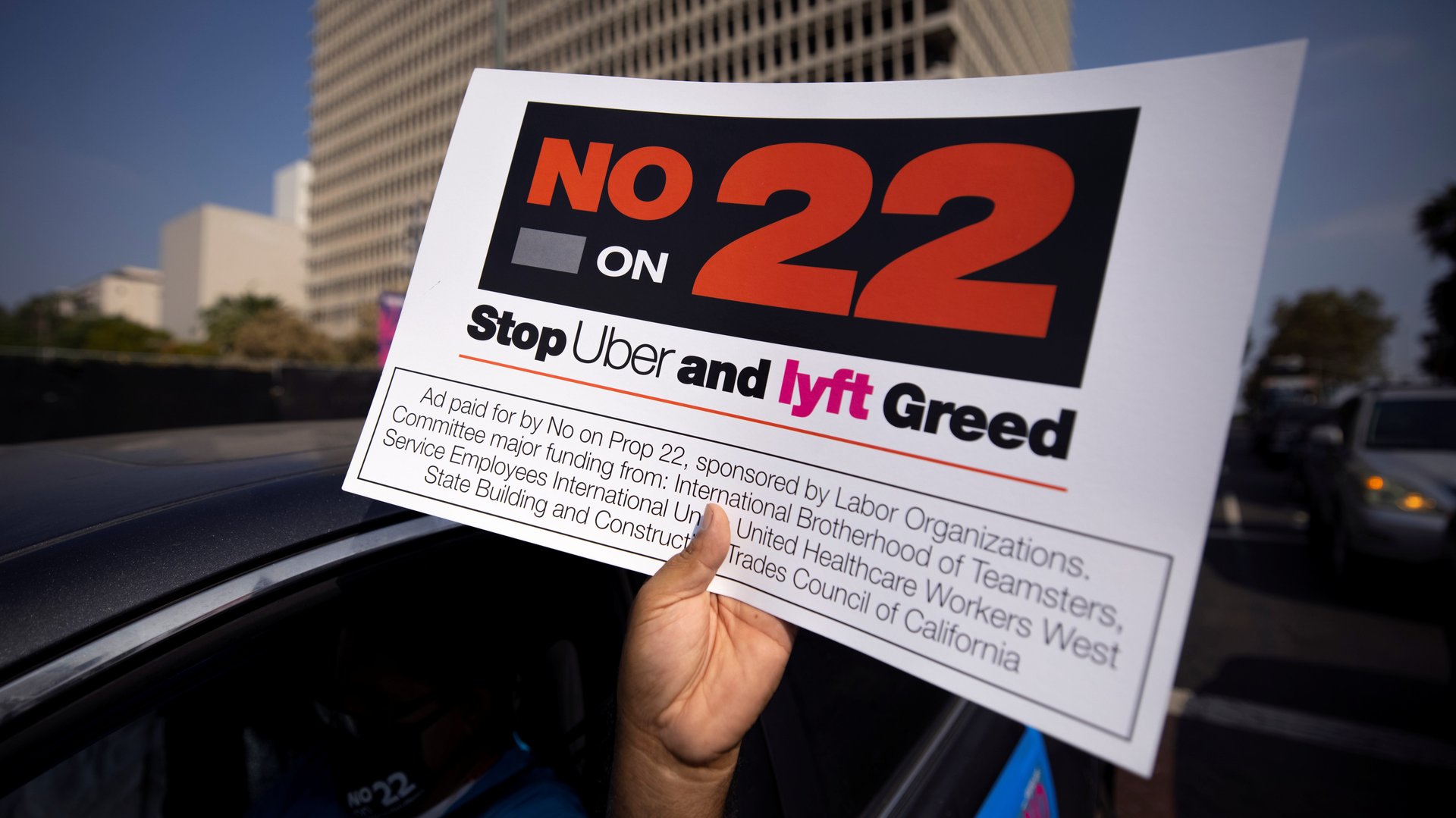

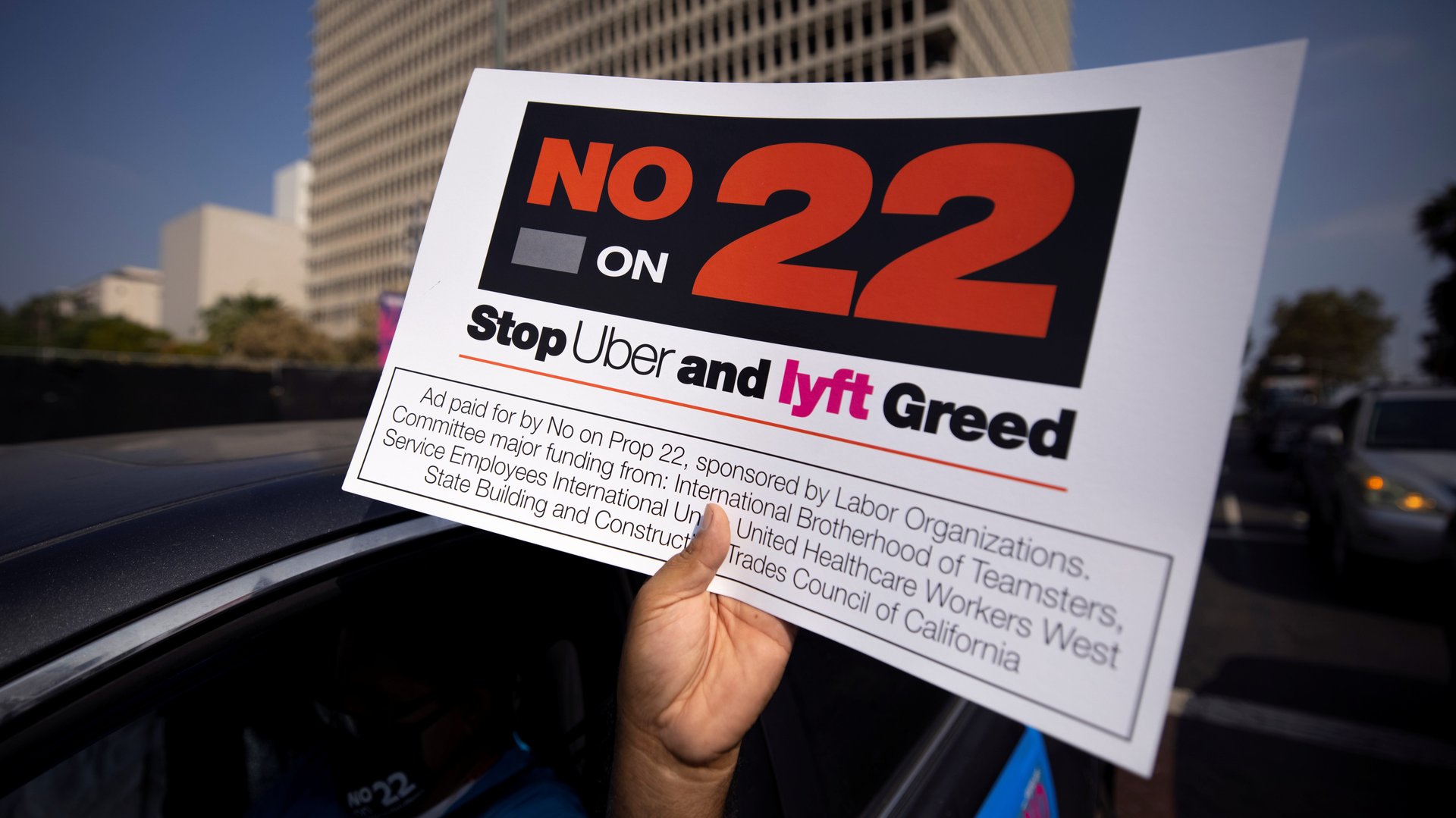

Reflecting the growing power of an industry that barely existed a decade ago, 58% of California voters sided with gig companies and exempted them from a new state law that would have upended their business models.

The passing of California ballot initiative Proposition 22 exempts gig companies like Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart from needing to classify their workers as employees and pay into benefits like workers’ compensation and health insurance. Instead, the companies will offer a limited package of new benefits in exchange for the right to keep their drivers and delivery workers classified as independent contractors—what Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi has called a “third way” for gig workers.

Now the companies plan to take the idea beyond California.

“Going forward, you’ll see us more loudly advocate for new laws like Prop 22,” Khosrowshahi said on a Nov. 5 call with investors. “It’s a priority for us to work with governments across the US and the world to make this a reality.”

Tony Xu, CEO and co-founder of DoorDash, echoed the sentiment. “Now, we’re looking ahead and across the country, ready to champion new benefits structures that are portable, proportional, and flexible…We look forward to partnering with workers, policymakers, community groups, and more to make this a reality.”

The fight against AB5

The gig companies pursued a long, aggressive battle against complying with the California labor law known as AB5, which makes it harder for companies to classify workers as independent contractors. The legislation went into effect on Jan. 1. But the companies circumvented the law, arguing that drivers are not employees—and, at one point, even threatening to pull out of California.

Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart banded together to bring the worker classification question to voters, culminating in the most expensive ballot initiative in California to date.

The Prop 22 outcome could set a precedent for how other lawmakers across the US approach the issue, perhaps discouraging other state attorneys general from filing lawsuits against ride-sharing companies, as Cowen analyst John Blackledge suggested in a Nov. 4 note to clients.

It also could influence states like New York, which has established a minimum wage standard for Uber drivers in New York City, as well as New Jersey, Virginia, and Washington, which have been looking into the AB5 model.

“I expect that across the country, this law is going to be looked at as a model,” says labor and employment lawyer Sandra Rappaport, a San Francisco-based partner at Hanson Bridgett. “Certainly the companies that employ these workers are going to be pushing for a law like this elsewhere.”

A new framework?

Most of the legal framework for employment models was developed long before the arrival of the internet—let alone smartphones and app-based platforms. The passing of Prop 22 reinforces the idea that gig workers don’t fit into a binary box of being either an employee or independent contractor, Rappaport says.

But labor advocates say it’s possible to both have flexibility and be an employee. Ken Jacobs, chair of the UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education, sees Uber’s hybrid model as an “old model wrapped in new technology,” with the companies shifting the costs and risks to workers.

Prop 22 is likely to be permanent in California—it includes a provision that requires a seven-eighths vote of the state legislature to change it.

Could it also end up influencing federal policy? Both US president-elect Joe Biden and his vice president, Kamala Harris, opposed Prop 22 and support addressing the worker-classification debate on a national level.

Under a Biden administration, the US Department of Labor is likely to propose more rules that protect workers. Rappaport says that could include rolling back the relaxed guidelines on classifying gig workers that the Trump administration rolled out in September. But if the Republicans hold onto their majority in the Senate, providing gig workers more protection at the federal level will likely be a bigger political fight.

Policy at the polls

The passing of Prop 22 doesn’t mean Uber is off the hook. The ride-hailing giant will have to fight battles in other states—and possibly lose some—as it was about to before Prop 22 was passed, says Rappaport. Some of the biggest advances in worker conditions, meanwhile, could come from more local pressure: In September, Seattle passed a minimum pay rate for Uber and Lyft drivers, modeled after the one passed in New York City. Because the measure only governs what happens after it goes into effect, Uber and Lyft could still owe billions of dollars in unpaid wages for violations, says Jacobs.

That said, the Prop 22 outcome could perhaps encourage other tech companies to go to the ballot to carve themselves out of the regulatory framework. There’s no guarantee it will work—and it certainly will be expensive—but Mark Lemley, director of the Stanford Program in Law, Science, and Technology, says it’s possible that “propositions may be the only way to make gig economy policy going forward.”