Parler’s explosive growth is rooted in half a century of US partisanship

Parler, a conservative social media platform that bills itself as a place where users can escape what it calls biased content moderation on Twitter and Facebook, has been downloaded more than 4 million times since the US presidential election on Nov. 3. It follows the trajectory of other conservative social networks, like Gab and Rumble, which have seen similarly explosive growth over the past two weeks.

Parler, a conservative social media platform that bills itself as a place where users can escape what it calls biased content moderation on Twitter and Facebook, has been downloaded more than 4 million times since the US presidential election on Nov. 3. It follows the trajectory of other conservative social networks, like Gab and Rumble, which have seen similarly explosive growth over the past two weeks.

But while the rise of these platforms has been sudden, the partisan forces driving their growth are quite old. Although explicitly political social media apps are a relatively recent invention, they have precedents that date back centuries.

An early parallel in American history is the partisan press of the 19th century. Just as newspapers then were typically funded by—and served as mouthpieces for—political parties, Parler is financially supported by Republican megadonor Rebekah Mercer, a hedge fund heiress known for bankrolling conservative candidates, think tanks, and political action committees. She has said she co-founded the platform as an alternative to Facebook and Twitter, which Republicans claim (without much evidence) are biased against conservatives.

While newspapers and social media apps function differently, they can serve a similar purpose by uniting partisans around a shared set of facts and analysis. “The idea that this is where you can go to get congenial news that fits with your views, and that the party is going to spend the money necessary to provide that space for you, is part of a much larger tradition in American history,” said Joshua Darr, an assistant professor of political communication at Louisiana State University.

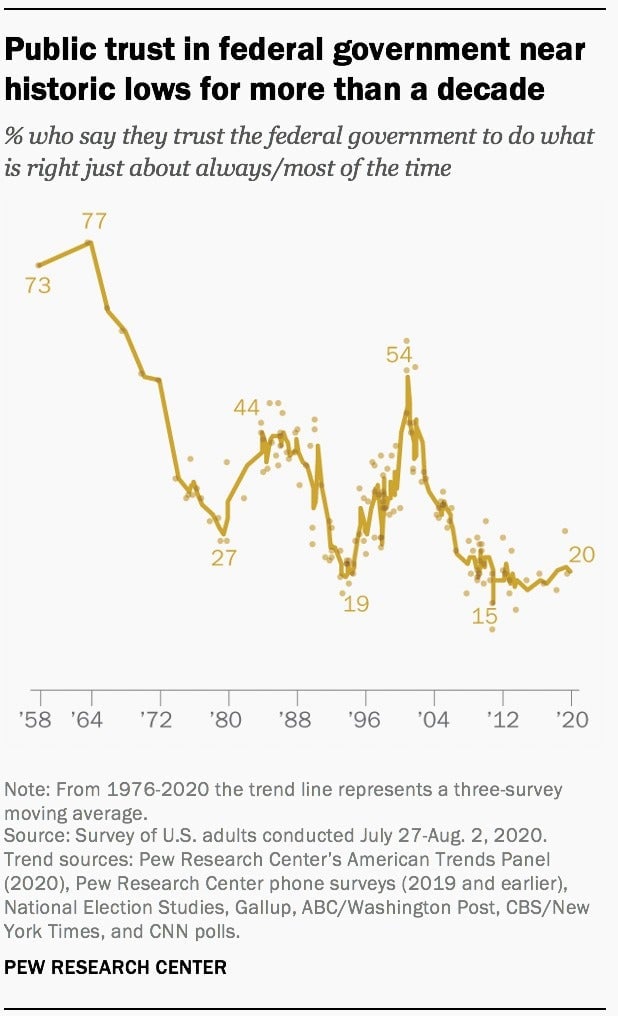

The current wave of partisanship in US politics, which ultimately gave rise to Parler, dates back to around the 1970s. That’s when public opinion polling shows Americans’ trust in government and the media beginning to tank. Meanwhile, affective polarization—that is, personally disliking members of the other party—began a long upswing that has continued to the present.

Many forces fueled that trend. Jennifer McCoy, a political science professor at Georgia State University who has studied the rise of partisanship from Venezuela to Turkey to Thailand, said the US followed the same path to polarization as many countries she has researched: Demographic changes, coupled with economic disruptions brought on by globalization, became a source of grievance, which political elites exploited to gain or retain power.

Against that backdrop, Republican politicians, starting with Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon, made allegations of liberal bias in the news media a core component of their political messaging—and it has remained a consistent mantra until the present day. After two decades of that drumbeat, in 1996, Fox News went on the air, marking the beginning of our current era of highly polarized cable news.

“When Fox arrived on the scene and called itself fair and balanced, they immediately had a pretty good audience that only kept growing because conservatives and Republicans…were feeling they’d been subject to media bias for the last 20 years,” said Johanna Dunaway, an associate professor of political science at Texas A&M University. “My inclination is to think the market demand that drove the rise of Fox is the same kind of market demand that’s probably driving the rise of Parler.”

In the meantime, local newspapers began to collapse—a trend correlated with the rise of partisanship. Over time, according to Darr, people have turned increasingly toward national news dominated by party conflict. Hyperpartisan digital outlets like Breitbart and the Daily Caller have proliferated. At the same time, political parties have backed partisan propaganda machines masquerading as impartial local outlets to sway public opinion.

The election of US president Donald Trump exacerbated existing trends, ratcheting up partisan animosity and amplifying Republican anti-media messaging. A slew of misinformation campaigns seeking to undermine the 2016 elections forced social media companies to ramp up their fact checking and moderation practices ahead of the 2020 election, stoking grievances among Republican politicians and pundits who saw the effort as another example of liberal bias.

All this set the stage for apps like Parler, Gabb, and Rumble to soar in popularity after this year’s contentious elections. They were helped along the way by a president making false claims of voter fraud that Twitter and Facebook aggressively moderated, and Republican politicians and Fox News pundits who responded by encouraging their followers to abandon traditional social platforms to flee their alleged censorship.

While Parler attracted much attention when it took the top spots on Apple and Google’s app stores just after the election, there are signs that its massive growth is already tapering off. But whether or not the app catches on, the long-term trends that brought it to the fore will remain.