A whistleblower and a cash problem: Caterpillar’s Swiss tax adventures

Today, US lawmakers are grilling Caterpillar executives for shifting profits overseas, and the whole thing rests on whether Caterpillar is a redundant part of its own supply chain.

Today, US lawmakers are grilling Caterpillar executives for shifting profits overseas, and the whole thing rests on whether Caterpillar is a redundant part of its own supply chain.

OK, we’ll explain.

The scheme

Caterpillar makes industrial equipment and engines, and does the job quite well—it’s hugely profitable and one of America’s biggest exporters. But beyond just selling equipment, Caterpillar sells replacement parts; its machines can last for decades, and in that time, its customers might spend two or three times the original cost on service and repair.

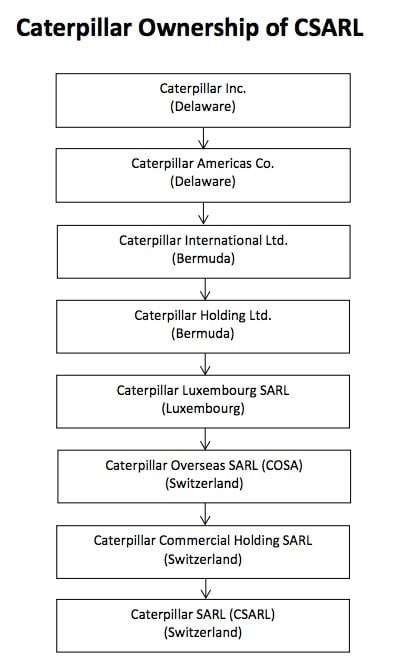

Most of those parts are made by third-party suppliers in the United States (though some are made overseas). Before 2000, 85% of the company’s parts sales were attributed largely to its US headquarters firm, with the rest split by foreign dealers. But, with the help of PricewaterhouseCoopers, the company rejigged its corporate structure to attribute 85% of its parts profits to a Swiss subsidiary, CSARL, by having its third-party suppliers sell directly to the Swiss subsidiary.

While the company’s actual operations didn’t change—a Caterpillar document said the restructuring had “minimal business

Is this illegal? That’s what the US Senate wants to know.

The whistleblower

Daniel Schlicksup was a Caterpillar executive in charge of the company’s international tax strategy. He took part in a review of the Swiss tax strategy that began in 2006. Multinationals frequently exploit legal loopholes in the tax code, but Schlicksup became concerned that the profit-shifting might be too close to the edge.

Particularly, Schlicksup worried that the restructuring had no “economic substance,” but was merely a tax avoidance scheme—a no-no under US tax rules. In 2007, he sent an e-mail to the company’s chief ethics officer saying ”the essence of the issue is that to my knowledge, the parts business is managed from the US, yet we are running the parts profits through Switzerland as if the business was managed by CSARL.”

In 2008, Schlicksup was transferred to another division, which he considered a demotion, and sued the company, alleging tax evasion. His suit was settled out of court in 2012, but the information it made public contributed to the Senate investigation. The US Internal Revenue Service has not investigated Caterpillar’s tax strategy, but two tax law professors at the Senate hearing who said the arrangement appeared to violate US laws pointed out that US tax collectors would not have had access to key documents surfaced by the investigations and lawsuits.

What’s fair?

Caterpillar says its tax strategy is perfectly legal, and notes that it paid an effective tax rate of 29% last year, higher than many multinationals, while employing 52,000 Americans. Another tax law professor provided an analysis for Caterpillar that describes the Swiss tax scheme as a “a sensible business decision to remove a redundant middleman.”

The “redundant middleman,” in this case, is Caterpillar, Inc., which still manages much of the inventory and movement of parts, and the sales of the machines they were built for.

Caterpillar’s defenders say that scrutiny like this—or tax law changes to make such schemes impossible—will drive the company and others like it out of the United States, thus depriving Americans of jobs and the government of taxes. But arguably, that’s just the point of making such tax schemes illegal. Caterpillar could move its actual operations to Switzerland—or Bermuda or Luxembourg—but the cost would be a lot higher than just making them appear Swiss on paper.