Electric airplanes are getting tantalizingly close to a commercial breakthrough

For $140,000, you can fly your own electric airplane. The Slovenian company Pipistrel sells the Alpha Electro, the first electric aircraft certified as airworthy by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in 2018. It’s a welterweight at just 811 pounds (368 kilograms), powered by a 21 kWh battery pack—about one-fifth the power of what you’d find in a Tesla Model S. For about 90 minutes, the pilot training plane will keep you and a companion aloft without burning a drop of fossil fuel.

For $140,000, you can fly your own electric airplane. The Slovenian company Pipistrel sells the Alpha Electro, the first electric aircraft certified as airworthy by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in 2018. It’s a welterweight at just 811 pounds (368 kilograms), powered by a 21 kWh battery pack—about one-fifth the power of what you’d find in a Tesla Model S. For about 90 minutes, the pilot training plane will keep you and a companion aloft without burning a drop of fossil fuel.

Those of us without a pilot license will have to wait longer for emissions-free flight—but not much. For all its challenges, 2020 has proven to be a milestone year for electric aviation. Electric aircraft set new distance records, replicated short commercial flight paths, won over the US military, and attracted buyers from big airlines.

And in June, European regulators granted another of Pipistrel’s aircraft, the Velis Electro, the world’s first electric “type certification,” deeming the entire aircraft design safe and ready for mass production (airworthiness only certifies individual aircraft).

🎧 For more intel on electric aviation, listen to the Quartz Obsession podcast episode on flying business class. Or subscribe via: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher.

Much more is coming. Within two years, you’ll be able to watch Air Race E, a circuit that pits eight electric-powered airplanes against each other, zooming just 32 feet (10 meters) off the ground at 280 mph (450 kph). Electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) leaders Archer, Joby, and Beta are reading their battery-powered flights on the question for certification.

“You’ve seen some shakeup in electric aviation, but also see it get closer to reality” in 2020, says John Hansman, director of MIT’s International Center for Air Transportation, and part of the hybrid-electric aircraft startup Electra. “It’s clear there will be the emergence of a new class of electric airplanes. Next year, you’ll see hybrid and battery aircraft in service or close to being in service.”

The remarkable advancement in batteries, electric motors, and other hardware installed in electric cars—as well as hundreds of millions of dollars in aviation applications—have brought electric technology much closer to commercial take-off after years of doubt. By 2035, investment bank UBS estimates, the aviation industry will be 25% hybrid or fully electric.

But the ascent hasn’t been without turbulence. In January, an all-electric prototype from Eviation burst into flames during ground testing at an Arizona airport, likely due to overheating batteries (the company says it will enter service by 2022). Uber sold off its aviation division, Elevate, to the startup Joby as the financial prospects for electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) remain too far from profitability for Uber’s struggling balance sheet.

“There’s a big difference between a demonstration airplane and an airplane you’re trying to certify,” Hansman said, referring to an FAA process that requires hundreds of millions of dollars over nearly a decade. But the new air race is on. Who will be the first to certify a commercial electric aircraft?

Why go electric?

Half of all global flights are shorter than 500 miles. That’s the sweet spot for electric aircraft. Fewer moving parts, less maintenance, and cheap(er) electricity means costs may fall by more than half to about $150 per hour (smaller airplanes like Pipistrel’s cost just a few dollars). For airlines, this makes entirely new routes now covered by car and train possible (and profitable) thanks to lower fuel, maintenance, and labor costs.

Electric propulsion nearly solves another problem for aviation: carbon emissions. Aviation emits more than 2% (pdf) of the world’s CO2 emissions, and it may reach nearly a quarter by mid-century. With no alternative fuel ready to leave the ground, and the number of air passengers set to double by 2035, electricity may offer the industry its best way forward in a climate-constrained world.

That’s likely to make 2021 the year of the hybrid. On the way to designing all-electric aircraft, electric aviation companies are modifying what works to stay aloft. This was Los Angeles-based Ampaire’s strategy with its “Electric EEL,” which pairs a combustion engine in the nose with and electric propeller motor in the rear. The modified Cessna 337 Skymaster is one of the first hybrids to win approval under the FAA’s experimental aircraft certification (only essential crew and personnel are allowed to fly).

In October, the EEL completed a 341-mile test flight between Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area, the longest electric-hybrid flight ever for a commercial aircraft, the company claims. Ampaire is now flying 15-minute trial flights in partnership with Hawaii-based Mokulele Airlines to prove the feasibility of quick trips between the islands’ small airports with mock payloads. In 2021, the company says it will start flying in the UK, work with NASA to overhaul its aircraft designs, build out a supply chain, and lay the foundation for its own vehicle, the Tailwind, a custom-built electric jet on the drawing board (and aerodynamic test chambers).

“Clean-sheet design”

The ultimate prize will be designing all-new electric aircraft. But certifying a new aircraft remains arduous and expensive. “It takes a lot of time and a lot of money to build a new planet from scratch,” says Kevin Noertker, co-founder of Ampaire. “It will be five to seven years before you get a clean-sheet design. A lot of companies are trying to prove us wrong, but if they succeed, it will be a much better world.”

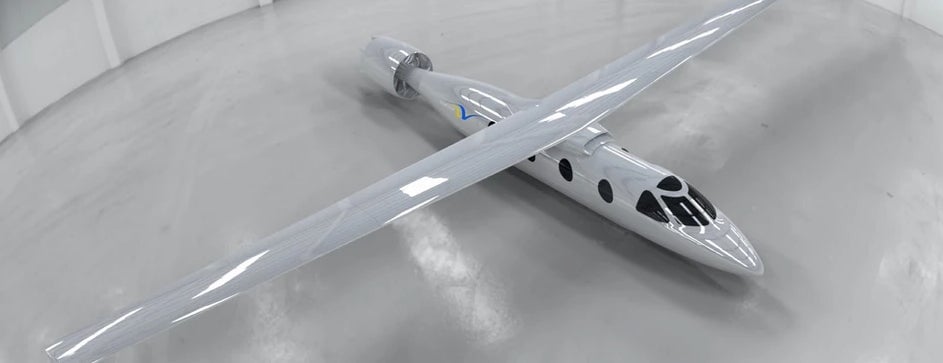

Eviation Aircraft is one of the startups furthest down this runway. Its new electric plane, Alice, made a splash after scaled-down version completed an autonomous demonstration flight at the Paris Air Show in 2017. Since then, reports Eviation, the nine-seat, $4 million plane has received more than 150 orders. For larger aircraft, Wright Electric says it is building a fleet of 186-seat electric airliners for the British budget airline easyJet due out by 2030.

Then there are the craft that need no runway at all. Air taxis, similar to overgrown drones, promise to bring the price and convenience of urban flight low enough to transform cities and same-day delivery. Archer Aviation’s eVTOL aircraft will ferry four passengers in its vehicles at speeds of up to 150 mph about 60 miles. “We’re building the world’s first all-electric airline,” says Adam Goldstein, co-founder of Archer. “You can expect us to fly in 2021.” The company is targeting urban routes at the price of an UberX, about $3 to $6 per passenger-mile. By 2024, it plans to get the public riding inside its vehicles. Archer, like rivals Joby and Beta, are all racing to secure FAA certification for their lines of aircraft.

The newest kids on the block are STOL (short take-off and landing) aircraft. These combine the simplicity and cost-savings of fixed-wing aircraft with extremely short take-off distances of 100 feet or less, about one-third of a football field. A string of electric motors along the wings generate extra lift, avoiding some of the engineering complexity and certification challenges facing eVTOLs.

All of them will face tough decisions to ensure the right technology makes it into the aircraft at a time when designs are rapidly evolving, says Matt Trotter of Silicon Valley Bank: “The pace of innovation in aviation right now is faster than we’ve ever seen from the entrepreneurs we speak with.” Fuel, autonomy, and form factors are all up for grabs. Batteries are cheap and easily available, but hydrogen looks increasingly attractive for flights over a few hundred miles (sourcing and storing it remains a challenge).

Autonomous commercial aircraft are finally taking off, too, and pairing pilot-free planes with electric propulsion could provide huge cost savings. But the FAA won’t let pilots leave the cockpit quite yet. And exotic aircraft forms are off the drawing board as small electric motors let aerospace engineers experiment with placing one—or a dozen—on various surfaces of the airframe.

All of this is forcing startups to develop aircraft that will accommodate different technologies likely to gain traction in the coming years. Jeff Engler, CEO of Wright Electric, says his company is “parallel processing” different designs as it prepares to certify an aircraft that can accommodate batteries, hybrid, or hydrogen. In all, about 200 electric aircraft were estimated to be under development in 2019, up one third from a year earlier.

Investors are eagerly betting on the sector. “The biggest change we’re seeing recently is access to capital for deep tech,” says Trotter. Since 2015, 10 of the leading electric aviation startups globally have raised more than $1.2 billion, most it in the last year (led by a $590 million round by Joby Aviation), according to PitchBook. Airlines are pouring money into the supply chain for electric propulsion. The investment arms for JetBlue Airways invested $250 million in electric-aviation startups over the last three years, and Intel, Toyota Motor, Daimler, and Geely Automobile in China are crowding into the space.

And the military is returning to its roots as an early funder of Silicon Valley technology: The Navy and Air Force are both providing funds, support, and testing for autonomous and electric cargo drones. Joby Aviation’s four-person eVTOL aircraft recently won an airworthiness certification from the Air Force to start flying military missions (19 other companies are in line to do the same).

These companies will need all the cash they can get. Electric aviation startups, predicts one airline executive, may need $17 billion (perhaps as much as $40 billion) to certify their aircraft and build their businesses, a significant share of venture capital each year. A few companies have already made crash landings. Zunum Aero, despite raising $6.8 million from investors including Boeing and JetBlue, ran out of money in 2018 and laid off 70 staff members (it’s now fundraising again). Without massive infusions of cash and new sources of revenue before their own craft are ready to fly, more companies are likely to join Zunum.

The electric aviation race will be as much against bankruptcy as rivals.